"It may seem partial in me to praise," replied Mary, looking around her, "but I must admire the taste my sister has shewn in all this. Even Henry approves of it, and his good opinion is not so easily won in matters horticultural."

"I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!" answered Miss Price, who did not appear to have heard her. "The evergreen! How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen!"

But as Miss Price happened to have her eyes fixed at that moment on a particularly fine example of an elm, Mary merely smiled and said nothing.

A few moments later, Miss Price began again in a rather different strain, "I cannot imagine what it is to pass March and April in London. How different a thing sunshine must be in a town! I imagine that in — Bedford-square was it not, my dear Miss Crawford? — the sun’s power is only a glare, serving but to bring forward stains and dirt that might otherwise have slept. And old gentlemen can be so particular about such things. I always pity the housekeeper in such circumstances. You, of course, know the trials of housekeeping only too well."

Miss Price having exhausted for the present even her considerable talent for the underhand and the insulting, began to pull at some of the trimming on her dress. "This cheap fringe will not do at all. I really must ask Lady Bertram to remonstrate with that slovenly dressmaker. I am hardly fit to appear in decent company, but thankfully there is no-one of consequence here to see me."

Mary watched her for a moment, reflecting that she did not have such an ornament on even her finest gown, before commenting thoughtfully, "I am conscious of being even more attracted to a country residence than I expected."

"Indeed?" said Miss Price loudly, with a look of meaning. "What had you in mind? Allow me to guess. An elegant, moderate-sized house in the centre of family connections — continual engagements among them — commanding the first society in the neighbourhood, and turning from the cheerful round of such amusements to nothing worse than a tête-à-tête with the person one feels most agreeable in the world? I can see that such a picture would have much in it to attract you, Miss Crawford."

"Perhaps it does." Mary added to herself, leaving her seat, "Perhaps I could even envy you with such a home as that."

Miss Price sat silent, once again absorbed in the vexations of her gown, and pulling at it until it was quite spoilt. Mary relapsed into thoughtfulness, till suddenly looking up she saw Edmund walking towards them in the company of Mrs Grant. The very consciousness of having been thinking of him as "Edmund’ — as Miss Price alone was justified in thinking of him — caused her to colour and look away, a movement which was not lost on the sharp eyes of Miss Price.

"Well, Miss Crawford," she said archly, "shall I disappoint them of half their lecture upon my sitting down out of doors at this time of year, by being up before they can begin?"

Edmund met them with particular awkwardness. It was the first time of his seeing them together since the beginning of that better acquaintance which he had been hearing deprecated by his mother almost every day. He could hardly understand it; there was such a difference in their tempers, their dispositions, and their tastes, there never were two people more dissimilar. But even if he saw the force of such a contrast, he was not yet equal to discuss it with himself, and seeing them together now, he confined himself to an insipid and common-place observation about the wisdom of judging the weather by the calendar, which would have merited an entry in Henry’s pocket-book, if he had but heard it.

As the four of them returned to the parsonage house, Edmund recollected the purpose of his errand; he had walked down on purpose to convey Sir Thomas’s invitation to the Grants and the Crawfords to dine at the Park. It was with strong expressions of regret that Mrs Grant declared herself to be prevented by a prior engagement, and Miss Price turned at once to Mary, saying how much she would have enjoyed the pleasure of her company, "but without Dr and Mrs Grant, she did not suppose it would be in their power to accept," all the while looking at Edmund for his support. But Mr Norris assured them that his uncle would be delighted to receive Mr and Miss Crawford, with or without the Grants, and in her brother’s absence Mary accepted with the greatest alacrity.

"I am very glad. It will be delightful," said Miss Price, trying for greater warmth of manner, as they took their leave. Edmund took her arm and they walked home together; and except in the immediate discussion of this engagement, it was a silent walk — for having finished that subject, Edmund grew thoughtful and indisposed towards any other. Miss Price narrowly observed him throughout, but she said nothing.

Chapter 3

At ten minutes after four on the appointed day, the coachman drove round and Mary and Henry set off across the park. As it happened, the Mansfield family had received a first letter from Mr William Bertram that very morning, and a whole afternoon had been insufficient to wear out their enthusiasm for accounts of how he had fitted up his berth, or the striking parts of his new uniform, or the kindnesses of his captain. The letter was produced again when the Crawfords arrived, and much made of its frank, unstudied style, and clear, strong handwriting. This specimen, written in haste as it was, had not a fault, and Mrs Norris expressed herself very glad that she had given William what she did at parting, very glad indeed that it had been in her power, without material inconvenience, to give him something rather considerable to answer his expenses, as well as a very great deal of invaluable advice about how to get everything very cheap, by driving a hard bargain, and buying it all at Turner’s.

"You are indeed fortunate that Mr William Bertram intends to be such a good correspondent," said Mary, examining the letter in her turn. "In my experience, young men are much less diligent creatures!" with a smile at Henry. "Normally they would not write to their families but upon the most urgent necessity in the world; and when obliged to take up the pen, it is all over and done as quickly as possible. Henry, who is in every other way exactly what a brother should be, has never yet written more than a single page to me; and very often it is nothing more than, "Dear Mary, I am just arrived. The grounds shew great promise, and thankfully there are not too many sheep. Yours &c"."

"My dear Miss Crawford, you make me almost laugh," said Miss Price, "but I cannot rate so very highly the love or good-nature of a brother, who will not give himself the trouble of writing anything worth reading, to his own sister. I am sure my cousins would never use me so, under any circumstances."

"I doubt there is a man in England who could so neglect Miss Price," said Henry gallantly, but received no other reward for his pains than Miss Price at once drawing back, and giving him a look of scorn.

A table was formed for a round game after tea, and Henry ventured to suggest that Speculation might amuse the ladies. Unwilling to cede the arrangement of the evening to anyone, and certainly not to either of the Crawfords, Mrs Norris protested that she had never played the game, nor seen it played in her life.

"Perhaps Miss Price may teach you, ma’am."

But here Fanny interposed with anxious protestations of her own equal ignorance, and although this gave Mrs Norris a further opportunity to press very industriously, but very unsuccessfully, for Whist, she quickly encountered the warm objections of the other young people, who assured her that nothing could be so easy, that Speculation was indeed the easiest game on the cards.

Henry once more stepped forward with a most earnest request to be allowed to sit with Mrs Norris and Miss Price, and teach them both, and it was so settled. It was a fine arrangement for Henry, who was close to Fanny, and with two persons’ cards to manage as well as his own — for though it was impossible for Mary not to feel herself mistress of the rules of the game in three minutes, Fanny continued to assert that Speculation seemed excessively difficult in her eyes, that she had not the least idea what she was about, and required her companion’s constant assistance as every deal began, to direct her what she was to do with her cards.

Soon after, taking the opportunity of a little languor in the game, Edmund called upon Mr Crawford to discuss his plans of improvement, it being the first time that the ladies had had the opportunity of questioning him on the subject.

"Mansfield’s natural beauties are great, sir," he replied, "such a happy fall of ground, and such timber! (Let me see, Miss Price; Mrs Norris bids a dozen for that knave; no, no, a dozen is more than it is worth. Mrs Norris does not bid a dozen. She will have nothing to say to it. Go on, go on.) With improvement Mansfield will vie with any place in England."

"And what in particular will you be suggesting, Mr Crawford?" asked Lady Bertram.

"My survey is not fully complete, ma’am, but I anticipate one or two major works that may put the estate to some expense."

"Well, the expense need not be any impediment," cried Mrs Norris. "If I were Sir Thomas, I should not think of the expense. Such a place as Mansfield Park deserves everything that taste and money can do. For my own part, I am always planting and improving, for naturally I am excessively fond of it.We have done a vast deal in that way at the White House; we have made it quite a different place from what it was when we first had it, and would have done more, had my poor husband lived. I am sure you would learn a great deal from the White House, Mr Crawford," finished Mrs Norris carelessly. "You may come any day; the housekeeper will be pleased to shew you around."

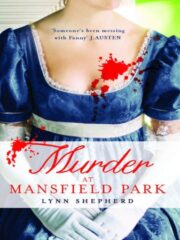

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.