Julia said nothing to her family of her encounter in the avenue, and spent so long in adding new touches to her drawing that her mother was already ringing the bell for dinner when she joined the other ladies of the family.

Mrs Norris began scolding at once."That is a very foolish trick, Julia, to be idling away all the day in the garden, when there is so much needlework to be done. If you have no work of your own, I can supply you from the poor-basket here. There is all this new calico that your mother bought last week, not touched yet."

Julia was taking the work very quietly, when her aunt suddenly exclaimed once more. "Oh! For shame, Julia! How can you shew yourself in the drawing-room in such a disgraceful state! — Look at you, quite covered with paint, and to be sure you have ruined this entire roll of cloth with your thoughtlessness. Do you have no thought for the waste of money? Be off with you now, and wash yourself, before your father sees you and mistakes you for one of the lesser servants."

There was indeed a very small speck of ink, quite dry, on Julia’s hand, but she knew better than to contradict her aunt, however unjust her accusations, and returned to her room to remedy it, her heart swelling with repressed injury at being so publicly mortified for so little cause. When she reappeared downstairs she was just in time to hear the name of her new friend. Maria had not long returned from her daily ride with the old coachman, and related, with much liveliness, that he had never seen a young lady sit a horse better than Miss Crawford, when first put on.

"I was sure she would ride well," Maria continued, "she has the make for it. Her figure is so neat and light."

"I am sure you are a fair judge, Maria," said Lady Bertram, "since you ride so well yourself. I only wish you could persuade Julia to learn. It is such a nice accomplishment for a young lady."

Mrs Norris, who was still in a decidedly ill temper, seemed to find this inoffensive remark particularly provoking, and after muttering something about "the nonsense and folly of people’s stepping out of their rank and trying to appear above themselves", she observed in a louder tone, "I am sure Miss Crawford’s enjoyment of riding has much to do with the fact that she is contriving to learn at no expense to herself. Or perhaps it is Edmund’s attendance and instructions that make her so unwilling to dismount. Indeed, I cannot see why Edmund should always have to prove his good-nature by everyone, however insignificant they are. What is Miss Crawford to us?"

"I admit," said Fanny, after a little consideration, "that I am a little surprised that Edmund can spend so many hours with Miss Crawford, and not see more of the sort of fault which I observe every time I am with her. She has such a loud opinion of her own cleverness, and such an ill-bred insistence on commanding everyone’s attention, whenever she is in company. And her manners, without being exactly coarse, can hardly be called refined. But needless to say I have scrupled to point out my observations to Edmund, lest it should appear like ill-nature."

"Quite so," agreed Mrs Norris. "Miss Crawford lacks delicacy, and has neither refinement nor elegance. Ease, but not elegance. No elegance at all. Indeed, she is quite the vainest, most affected, husband-hunting butterfly I have ever had the misfortune to encounter."

The gentlemen soon joined them, and Mr Norris took a seat by Miss Price, and being unaware of the conversation that had passed, ventured to ask her whether she wished him to ride with her again the next day.

"No, not if you have other plans," was her sweetly unselfish answer.

"I do not have plans for myself," said he, "but I think Miss Crawford would be glad to have the chance to ride for a longer time. I am sure she would enjoy the circuit to Mansfield-common. But I am, of course, unwilling to check a pleasure of yours," he said quickly, perhaps aware of the dead silence now reigning in the room, and his mother’s black looks. "Indeed," he said, with sudden inspiration, turning to his cousins,"why should not more of us go? Why should we not make a little party?"

All the young people were soon wild for the scheme, and even Fanny, once properly pressed and persuaded, eventually assented. Mrs Norris, on the other hand, was still trying to make up her mind as to whether there was any necessity that Miss Crawford should be of the party at all, but all her hints to her son producing nothing, she was forced to content herself with merely recommending that it should be Mr Bertram, rather than Mr Norris, who should walk down to the parsonage in the morning to convey the invitation. Edmund looked his displeasure, but did nothing to oppose her, and, as usual, she carried the point.

The ride to Mansfield-common took place two days later, and was much enjoyed at the time, and doubly enjoyed again in the evening discussion. A successful scheme of this sort generally brings on another; and the having been to Mansfield-common disposed them all for going some where else the day after, and four fine mornings successively were spent in this manner. Everything answered; it was all gaiety and good-humour, the heat only serving to supply inconvenience enough to be talked of with pleasure, and to make every shady lane the more attractive. On the fifth day their destination was Stoke-hill, one of the beauties of the neighbourhood.Their road was through a pleasant country; and Mary was very happy in observing all that was new, and admiring all that was pretty. When they got to the top of the hill, where the road narrowed and just admitted two, she found herself riding next to Miss Price. The two of them continued silent, till suddenly, stopping a moment to look at the view, and observing that Mr Norris had dismounted to assist an old woman travelling homewards with a heavy basket, Miss Price turned to her with a smile. "Mr Norris is such a thoughtful and considerate gentleman! Always so concerned to appear civil to those of inferior rank, fortune, and expectations."

Seeing that her companion was most interested to observe the effect of such a remark, Mary contented herself with a smile. Miss Price, however, seemed determined to continue their conversation, and after making a number of disdainful enquiries as to the cost of Mary’s gown, and the make of her shoes, she continued gaily, "You will think me most impertinent to question you in this way, Miss Crawford, but living in this rustic seclusion, I so rarely have the opportunity of making new acquaintance, especially with young women who are accustomed to the manners and amusements of London — or at least such entertainments as the public assemblies can offer."

At this she gave Mary a look, which meant, "A public ball is quite good enough for you." Mary smiled. "In my experience, private balls are much pleasanter than public ones. Most public balls suffer from two insurmountable disadvantages — a want of chairs, and a scarcity of men, and as often as not, a still greater scarcity of any that are good for much."

"But that is exactly my own feeling on the subject! The company one meets at private balls is always so much more agreeable."

"As to that," replied Mary, "I confess I do not want people to be very agreeable, as it saves me the trouble of liking them a great deal."

She hazarded a side glance at her companion at this, wondering whether she was as accustomed to being treated with contempt, as she was to dispensing it, but Miss Price seemed serenely unaware that such a remark could possibly refer to her.

"Oh! My dear Miss Crawford," she said, "with so much to unite us, would it not be delightful to become better acquainted?"

To be better acquainted, Mary soon found, was to be her lot, whatever her own views on the matter. This was the origin of the second intimacy Mary was to enjoy at Mansfield, one that had little reality in the feelings of either party, and appeared to result principally from Miss Price’s desire to communicate her own far superior claims on Edmund, and teach Mary to avoid him.

The weather remained fine, and Mary’s rides continued. The season, the scene, the air, were all delightful, and as the days passed Mr Norris began to be agreeable to her. It was without any change in his manner — he remained as quiet and reserved as ever — but she found nonetheless that she liked to have him near her. Had she thought about it more, she might have concluded that the anxiety and confusion she had endured since her uncle’s death had made her particularly susceptible to the charms of placidity and steadiness; but for reasons best known to herself, Mary did not think very much about it. She had by no means forgotten Miss Price’s insinuations, and could not fail to notice Mrs Norris’s rather more pointed remarks; and in the privacy of the parsonage her brother continued to ridicule Edmund as both stuffy and conceited. He began a small collection of his more pompous remarks, which he noted down in the back of his pocket-book, and performed for his sisters with high glee, mimicking his victim’s rather prosing manner to absolute perfection. Perhaps Mary should have apprehended something of her own feelings from the growing disquiet she felt at this continued raillery, but unwelcome as it was, she chose rather to censure Henry’s lack of manners, than her own lack of prudence.

Mary rode every morning, and in the afternoons she sauntered about with Julia Bertram in the Mansfield woods, or — rather more reluctantly — walked with Miss Price in Mrs Grant’s garden.

"Every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with how much has been made of such unpromising scrubby dirt," said Miss Price, as they were thus sitting together one day. "Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as anything, or capable of becoming anything."

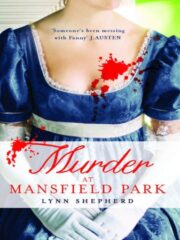

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.