"Secure this harpy’s hands, and take her down to the cellar," he said, with an expression of disgust. "She is not fit for decent company. And make sure to lock the door behind you."

"Aye, sir. It’ll be my personal pleasure."

"And call Stornaway in from the garden. I need to send him at once in search of the physician."

Fraser nodded, and hoisted the screaming woman over his shoulder, and made towards the door, while she all the while hurled invective at anyone prepared to listen.

"And you can tell that slattern Mary Crawford that I insist she cleans that blood off the carpet before she goes, even if it means getting down on her hands and knees and scrubbing it herself.That carpet is genuine Turkey, I’ll have you know, and cost me fifteen shillings a yard from Laidler’s, and that does not even include the cost of carriage — "

As soon as the door had closed behind them, Maddox went to Mary Crawford and knelt down beside her. The wound on her brow was bleeding profusely, and she was still unconscious; Norris remained sprawled over the chair, his head thrown back, and his mouth hanging open. Maddox took out his handkerchief, and folded it into a wad. The blood seeped into the fine linen, as he pushed her smooth dark hair away from the gash; he had never touched her before, beyond the briefest of hand-shakes, and his fingers trembled at the contact with her skin. If he had tried to deny his emotions before that moment, he could do so no longer.

He was still bent over her when he heard the sound of footsteps, and saw Stornaway’s tall thin frame at the door, followed hard by Henry Crawford. The latter could not possibly have had any apprehension of what he was about to see, and he stood for a moment, gazing in horror at the scene before him — the man with his sister’s head in his lap, the blood on her face, and on his hands. A moment later Maddox found himself hauled up by the collar, and pushed violently against the wall.

"What the devil has happened here?" cried Crawford. "What have you done to my sister? If she is harmed, I swear to God I will kill you with my own bare hands — "

Stornaway had by this time seized Crawford by the shoulders, in an endeavour to pull him away, but Crawford was the stronger, and his hands began to tighten round Maddox’s neck.

"I am waiting, Maddox," he hissed, his eyes fixed on the thief-taker’s.

"You would do better to release my throat, sir, and allow me to send my man for the physician. Mr Norris’s life, if not your sister’s, may depend upon it."

The grip slackened, and Crawford took a step back. Maddox nodded to Stornaway, who turned at once, and left the way he had come.

"What in heaven’s name is going on?" said Crawford, as he sank to his knees, and took Mary in his arms.

"The person who killed your wife has just attempted to murder your sister. Thankfully, I was close by, and able to intervene in time."

"But who? Why?"

Maddox looked down at his distraught face, "All in good time, Mr Crawford. The more urgent necessity at this moment is to convey Mr Norris upstairs to his bed. And then we will do whatever is necessary to assist your sister. She is a remarkable young woman, sir. A remarkable young woman indeed."

Chapter 21

When Mary opened her eyes it was to see Charles Maddox sitting at her side. She was lying down, with a blanket about her, and there were lamps burning in the room. Something was obscuring her left eye, and she put up her hand to find a thick cloth bandage had been wound about her head. She stared at Maddox for a moment, her vision still blurred, then endeavoured to sit up.

"Have a care, my dear Miss Crawford. You have had a terrible shock, and are not yet fully recovered."

She looked around at the room; her head was painfully heavy, but her mind clearing; she was starting to remember what had happened — and why she now found herself lying on a sopha in the drawing-room at the White House. Mrs Norris had attacked her, and Edmund —

"Where is he?" she said quickly. "He needs help — he was given — "

" — a fatal dose of laudanum, I know. Fear not, Miss Crawford; he is in the best hands. Mr Gilbert and Mr Phillips are upstairs with him now.We were able to get help to him quickly, and purge the system before the poison took full effect. He is still very ill, but they are in hopes that no mortal damage has been done. If he lives, he will have much to thank you for."

Mary turned away, her eyes filling with tears; it was too much. Charles Maddox watched her for a moment.

"I am afraid I cannot offer you the use of my handkerchief; I had to use it to staunch the bleeding. The cut you have sustained is deep, and you lost a quantity of blood. Mr Gilbert has done his best to dress it, but you have, I fear, quite ruined your gown." He smiled. "This time, at least, there is no need to prove that the blood is indeed your own."

"You have cuts on your own hand," she said weakly.

Maddox shook his head dismissively. "I have borne far worse in the past. These are mere scratches, incurred in the process of unlawful entry into Mrs Norris’s house."

Mary nodded slowly; she had no memory of such a thing, but it must indeed have been so, though in all her girlish dreams of a princely rescuer riding to her deliverance on a milk-white palfrey, he had never taken on such a shape as Maddox.

"How can I thank you," she began. "Had you not happened to be there — "

He got up and went to the side-table and poured a little wine, all the while avoiding her eye. "I think you should drink what you can of this," he said. "As to my presence, you will find out soon enough that it was not quite so fortuitous as it might seem. This case has been one of the most demanding of my career. The evidence pointed first one way, and then another. I will confess, Miss Crawford, that until very recently I was fully convinced that it was your brother who was responsible. No-one had a better motive than he."

"But — "

Maddox held up his hand. "As I said, that was what I had thought. You may possibly be aware that I have deployed my men to gather information."

"To listen at doors, you mean."

"On occasion, yes. You look reproving, and no doubt it is not a very commendable activity, but murder is not a very commendable activity either, and as we have discussed together once before, I am sometimes forced to employ methods that fine ladies and gentlemen find distasteful, in order to discover the truth.This was one such circumstance."

He took the empty glass from her hand, and sat down beside her once more.

"When you met Mr Norris at the belvedere, your tête-à-tête was not, as you believed, à deux, but à trois. My man Stornaway was listening."

Mary flushed, and she felt the wound above her eye begin to throb. "That was an outrageous intrusion, Mr Maddox — "

"Perhaps. Perhaps not. It has, however, been of the most vital importance in elucidating this case. Stornaway could not hear every word, but he did discern enough. Thus when Mr Norris came to me and confessed, I knew at once that it was a complete invention from beginning to end. A few pertinent — or impertinent — questions on my part were enough to put the matter beyond question. Unlike almost everyone else in the house, Mr Norris had actually seen Mrs Crawford’s body, so he was able to describe the injuries he had supposedly inflicted with tolerable accuracy. However, he had absolutely no idea that Miss Julia Bertram had died anything other than a perfectly natural, if lamentable, death. I knew, then, that he was lying."

"So why did you arrest him? Why confine him here like a criminal, and let us all believe him guilty? How could you do such a thing?"

"Because I had no alternative. And if you recall, I did go to great lengths to ensure that he would not be removed to Northampton, nor suffer the indignities of the common jail."

Mary turned her face away, and he saw, once more, the thinness of her face, and the hollowness under her eyes; she had clearly suffered much in those two days.

"Besides," he continued, "I wished to keep him here in Mansfield for my own reasons. Given that Mr Norris had clearly not committed the crime, there was only one possible reason why he should have chosen to confess to it. He was protecting someone; someone for whom he felt either duty and responsibility, or great affection. Someone he perceived to be weaker than himself, and less capable of enduring the punishment that must attend such a heinous crime. In short, a woman."

He got to his feet and began to walk about the room, his hands clasped behind his back. "I was convinced, for some time, that this woman was you, Miss Crawford. I had you watched at all times, I intercepted your letters, and subjected your behaviour to the most intense scrutiny. I know your habits, I know all your ways; what time you prefer to breakfast, and where you prefer to walk. I know everything about you — I have made it my business to know. Despite all my efforts, I saw nothing to indicate that you yourself were guilty.You were distressed, but I was forced to acknowledge that this was the natural distress of a woman who knows the man she loves is about to sacrifice himself needlessly for her sake."

Her face was, by now, flushed a deep red, but she did not turn to look at him.

"And so I turned my attention elsewhere. I had initially dismissed Mrs Norris as a possible murderess, on account of her age, but it seems I did not fully appreciate her physical strength, nor her formidable capacity for jealousy and resentment. It was the poisoning of Julia Bertram that forced me to think again. The killing of Mrs Crawford had always seemed to me to be the work of a man — the brutality, the bodily vigour it required — but poisoning is, in my experience, very much a woman’s crime. And who was better placed than Mrs Norris to perpetrate the act? The whole household went to her with their coughs and sore throats and arthritic joints, and no-one — not even you, Miss Crawford — would have questioned her presence in the sick-room."

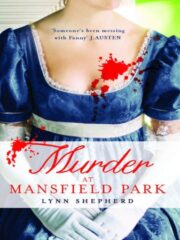

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.