Mr Norris made no reply and continued, "Is there anything you particularly wish to see, Crawford?"

"Sir Thomas’s letter talked of an avenue. I should like to see that."

"Of course, you would not have been able to see it last night, for the drawing-room looks across the lawn. Yes, the avenue is exactly behind the house; it begins at a little distance, and descends for half a mile to the extremity of the grounds. You may see something of it here — something of the more distant trees. It is oak entirely. But have a care, Crawford, you will lose my cousin Julia as a friend if you propose to have it down. She has a young girl’s romantic attachment to the avenue; she says it makes her think of Cowper."

""Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited,"" said Mary, with a smile. "The park is certainly beautiful at this time of year. The woods are some of the finest I have ever seen."

"Indeed," said Miss Price, looking at her with evident surprise. "I had not expected someone so used to the bustle and dirt and noise of London to feel the pleasures of spring so keenly. The animation of body and mind that one can derive from the beginnings and progress of vegetation, the increasing beauties of the earliest flowers — when all is freshness, fragrance, and verdure!"

There was a short silence, then Mr Norris returned to Henry. "It is some distance, I am afraid, from this spot to the avenue, and I fear Miss Crawford may have had walking enough for this morning."

"I am not tired, I assure you," said she. "Nothing ever fatigues me but doing what I do not like, and nothing pleases me more than accompanying Henry on his visits. I rarely have a gratification of the kind."

Mr Norris nodded gravely, and then continued to address Henry, "All the same, the park is large — full five miles around — and your survey of the grounds would be better taken on horseback."

"My dear Edmund," said Miss Price, "you forget that a man such as Mr Crawford can scarcely afford to keep three hunters of his own, as you do. But there must be some horse or other in my uncle’s stable that nobody else wants, that Mr Crawford could use while he is here?"

Henry made a low bow. "Miss Price is all consideration, but I can assure her that her generous concern is quite unnecessary. Dr Grant has offered me the loan of his road-horse, and as for Mary, well, she is no horsewoman, so the question does not arise."

"Would it interest you to learn to ride, Miss Crawford?" asked Mr Norris, speaking to her for the first time. His addressing her at all was so unexpected that Mary hardly knew what to say, and felt she must look rather foolish, but whatever her confusion, she was still able to observe that, although endeavouring to appear properly demure, Miss Price’s disapprobation was only too evident. Mary thought that Mr Norris must perceive it likewise, and presumed that no more would be said on the subject. What, then, was her increase of astonishment on hearing Mr Norris repeat his offer, adding that he had a quiet mare that would be perfectly fitted for a beginner. What, thought Mary, could he mean by it? Surely he could not be unaware of Miss Price’s views on the subject? But quickly recovering her spirits, she decided that if he saw fit to ignore Miss Price’s feelings, there was no reason for her to respect them, and she accepted the offer with enthusiasm, saying that it would indeed give her great pleasure to learn to ride.

The next morning saw the arrival of Mr Norris at the parsonage, attended by his groom. Henry, who had been waiting with Dr Grant’s horse, lingered only to see Mary lifted on hers before mounting his own and departing for a day’s ride about the estate.

With an active and fearless character, and no want of strength and courage, Mary seemed formed to be a horsewoman, and made her first essay around Dr Grant’s meadow with great credit. When they made their first stop she was rewarded with expressions more nearly approaching warmth than she had so far heard Mr Norris utter, but upon looking up, she became aware that Miss Price had walked down from the Park, and was watching the two of them intently, from her position at the gate. They had neither of them seen her approach, and Mary could not be sure how long she had been there. Mr Norris had just taken Mary’s hand in order to direct the management of her bridle, but as soon as he saw Miss Price, he released it, and coloured slightly, recollecting that he had promised to ride with Fanny that morning. He moved away from Mary at once and led her horse towards the gate. "My dear Fanny," he said, as she approached, "I would not have incommoded you for the world, but Miss Crawford has been making such excellent progress, that I did not notice the hour. But," he added in a conciliatory tone, "there is more than time enough, and my forgetfulness may even have promoted your comfort by preventing us from setting off half an hour sooner; clouds are now coming up, and I know that you dislike riding on a hot day."

"My dear Edmund," said Fanny, with downcast eyes, "it is true that my delicate complexion will not now suffer from the heat as it would otherwise have done. I was wondering that you should forget me, but you have now given exactly the explanation which I ventured to make for you. Miss Crawford," she said, turning her gaze upon Mary, "I am sure that you must think me rude and impatient, by walking to meet you in this way?"

But Mary could not be provoked. "On the contrary," she said, "I should rather make my own apologies for keeping you waiting. But I have nothing in the world to say for myself. Such dreadful selfishness must always be forgiven," she said with a smile, and an arch look at Miss Price, "because there is no hope of a cure."

And so saying, Mary sprang lightly down from the mare and after thanking Mr Norris for his time and attention, she walked hastily away, turning only to watch the two of them slowly ascend the rise, and disappear from her view.

Mary found her spirits unexpectedly unsettled, and carried on walking for some while, hardly knowing where she was heading, and engrossed in her own thoughts, until she suddenly became conscious of a line of ancient oak trees stretching to her right and left. She perceived at once that she must be in that very avenue of which she had heard so much, and was surprised to find that she had walked so far. She was on the point of turning back when her eye was caught by a figure seated under one of the trees, and a moment later she recognised the youngest Miss Bertram, intent on her sketch-book, inks, and pencils.

"Will I disturb Miss Julia if I join her for a few moments?" Mary asked as she approached the bench.

Julia looked up with a sad smile."In truth, Miss Crawford, I would welcome the interruption. I have been trying to capture the exact effect of the sunlight on the leaves, but it is, for the moment, eluding me."

Mary looked over the girl’s shoulder at the drawing, and was agreeably surprised at what she saw.There was a peculiar felicity in the mixture of the colours, even if the more disciplined guidance of a proper drawing-master seemed to have been wanting. Mary could not but wonder why Sir Thomas had not provided such tuition for his daughter; the expense would be nothing to a man in his position. But putting the thought aside for the moment, she resolved to speak to Henry when she returned to the parsonage; as far as she was able to judge, Miss Julia had a more than everyday talent, and her brother might perhaps be able to offer some assistance. The two of them sat companionably for some minutes more, looking at the view and talking of poetry. Their taste was strikingly similar — the same books, the same passages were loved by each, and Julia brought all her favourite authors forward, giving Thomson, Cowper, and Scott their due reverence by turns, and finding a rapturous delight in discovering such a coincidence of preference.

"And your sister?" Mary enquired, after a pause. "Does she share your enjoyment of reading?"

Julia smiled gravely. "Alas, no. Maria and I used to read together at one time, but her thoughts now are all of balls and gowns and head-dresses, and other such idle vanities. No," she said, with a faltering voice, and tears in her eyes, "now that my beloved William is at sea, there is no-one in whom I can confide."

She sighed, and was silent for a moment, gazing at the vista before them. "I had hoped to follow the course of his ship on the map in the school-room, but he could not be sure of his exact route. My father has promised that this picture I am drawing will be sent to William in Bahama, if I can perfect it."

Mary gently touched her arm, and observed, "I am sure the gift will be all the more precious to him, because it comes from your own hand."

"This was our favourite place," Julia continued, with more animation. "How many times have we sat together under these beloved trees! I always come here when I wish to think of him. We so loved to watch the progress of the seasons, and see the leaves change colour from the freshest green to the autumn glories of gold and red and brown."

"In that case I am sure you must spend many happy hours with your cousin," said Mary. "Only yesterday I heard Miss Price rhapsodising about the beauties of spring."

In spite of herself, Julia could not help half a smile. "That does not surprise me — Fanny is much given to "rhapsodising" of late. She believes it shews her to have elegant taste and — what was her phrase? — "sublimity of soul". And such romantic sensibilities are, of course, exceedingly fashionable just at present."

It was Mary’s turn to smile at this, and an unexpected gust of wind then nearly shaking the sketch-book from Julia’s hands, the two of them jumped up and began to walk back towards the house. By the time they reached the terrace something like friendship had already been established between them, notwithstanding their differences in age and situation. They parted with affectionate words, and Mary returned at last to the parsonage.

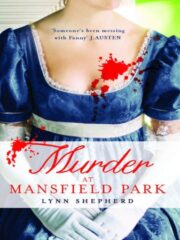

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.