When Dr Grant turned his attention to the late Mrs Crawford, Maddox was aware of an immediate and decided change in the mood in the church; there was little evidence of sorrow now, whether real or feigned, and the few murmurings that came to Maddox’s ears were expressions of sympathy for the plight of Mr Norris, a fact which he found both surprising and instructive. Nor did Maddox envy the clergyman his task: it was clear that, were it any other young woman but Sir Thomas’s niece, Dr Grant would have deemed it his Christian duty to present her fate as an awful warning to the congregation, and a caution against the evils of lust and avarice, but he was painfully constrained by the presence of his patron, and the demands of common politeness. It demanded all the ingenuity of a casuist to steer a safe course through such dangerous waters; to bury Mrs Crawford without praising her, and give an account of her life without referring to the husband who had seduced her, or the cousin who would be charged on the morrow with having done her to death. The husband, at least, had the good grace to appear abashed, and while Henry Crawford held his head high in the family pew, there was a spot of colour on each cheek that spoke either of a considerable suppressed anger, or an inner regret rising to wretchedness; even Maddox, with all his aptitude for physiognomy, could not determine which. It was of a piece with what he had come to know of the man, and he laid up this latest observation alongside the new intelligence Fraser had brought with him from Enfield. Henry Crawford was a conundrum that appeared to grow more complex the more closely he examined it; he had yet to decide if the solution to that conundrum was a matter of intellectual curiosity, or something more significant, but he hoped he might not have to wait very much longer to obtain his answer.

When the service was concluded, the gentlemen rose to accompany the coffins down into the family vault, and the assembled mourners waited in respectful silence; a silence broken only by the quiet weeping of Evans, and the whispered words of comfort offered by the housekeeper. Several minutes elapsed before Sir Thomas reappeared, his own face as white as if iced over by death. His halting progress down the aisle, supported by his son, was pitiful to see, and Maddox wondered whether the old gentleman’s health might never recover from the series of shocks he had sustained. Maddox was one of the last of the mourners to attain the door, and what he saw outside did not surprise him: there was a crowd of people thronging the churchyard, but both Henry Crawford and his sister were gone.

The knell was still tolling behind her as Mary made her way quickly to the rear gate of the White House. She had only visited the house once, quite early in her stay at the parsonage, but she remembered it very clearly, having spent an extremely tedious hour being taken through every room by Mrs Norris, who did not scruple to point out every chair, table, silver fork, and finger-glass, and who could enumerate the price of every item with as much facility as an agent shewing the house to a prospective tenant. Henry had warned her to remain out of sight until she saw him on the terrace with Stornaway; the man was said to be partial to snuff, when he could get it, and Henry had still a plentiful supply of fine Macouba that he had purchased in St James’s. It was hardly subtle, by way of a bribe, and should the man prove suspicious, Henry was not at all sure how he was to explain his sudden presence in the house; if pressed, he intended to claim he bore a message from Sir Thomas, enquiring as to the arrangements for Mr Norris’s removal, but it was, at best, a poor excuse, as any astute sentinel would know; they must hope that Maddox chose his subalterns for their physical not their mental prowess.

The minutes passed slowly by, and Mary began to fear that the White House servants would return long before she would have the opportunity to see Edmund; but just at the moment when she was about to give up hope, the door opened and she saw her brother and Stornaway emerge onto the terrace. Her heart was by this time beating so hard and so quick, that she could scarcely draw breath, far less move, but move she must; there was no time to be lost. She waited until the two men had disappeared round the side of the house, then slipped up the garden path, and through the open door into the drawing-room. She could hardly believe that she had actually attained the house without being detected, and stood motionless on the threshold, hardly knowing what to do next. She and Henry had spent so long discussing how she might gain access to the house, that they had barely touched upon what she should do once she had achieved it. But her customary self-possession did not fail her; she went quickly to the door, and stood in the hall, listening intently. At first the whole house seemed utterly quiet, but as her senses adjusted to the silence, she perceived that there was a strange, low, rasping sound emanating from a room quite close by; were it not for the time of day, she might have supposed there was someone sleeping there. She crept softly along the hall and stopped at the foot of the staircase; to her left the breakfast-parlour, to her right the dining-room, its door standing ajar. The sound, whatever it was, originated from there. Something impelled her forward, she knew not what, and almost without daring to breathe, she placed her hand to the door and pushed it open.

He was there. At the table, as if to eat — and there was, indeed, a plate at his side — but he was no longer sitting, no longer upright; he was slumped over the table, his head between his arms, his face half-concealed. She made a move towards him, then stopped, noticing for the first time the bottle and empty glass at his hand. She had never known him intoxicated — had thought, indeed, that he had an aversion to strong liquor in all its forms — and yet here he was, in the middle of the day, in a state of apparent drunkenness.

Her first feeling was one of guilty remorse — had she really brought him to this? — but a moment’s further observation led her to question her first response. There was still more than half a bottle of wine remaining, and he could not possibly have been reduced to such a state after imbibing so small a quantity. He bore all the signs of intoxication — the stertorous respiration, the flushed face — but as she moved closer, she could not discern the breath of wine.

"Mr Norris?" she said, hesitatingly. "May I speak to you for a moment?"

There was no reply.

Summoning all her courage, she put out a hand and took him by the shoulder, and spoke again, as loudly as she dared,"Mr Norris? Are you awake?"

Once more, she received no reply, but the propinquity in which she now stood allowed to observe him more closely, and she perceived that his stupefaction did not so much resemble the effects of drink, as the terrifying torpor into which Julia Bertram had descended, and from which they had not been able to reclaim her. She reached for the glass at once, and seized it with fumbling fingers; her suspicions were correct — there was a strong odour of laudanum.

"My God!" she cried. "What have you done — what have you done?"

She dragged him to an erect position, his head lolling over one shoulder, and saw, with terror, that his face was beginning to take on the same deep suffusion of blood that she had seen only a few days before. This time, at least, she knew what to do. She moved first towards the bell to ring for assistance, before she recollected that the servants were all absent; she turned towards the door, thinking to call for aid from her brother and Stornaway, but she never reached it.There was already someone standing there, with her hand to the door-handle, and a basket of cutlery over one arm.

"Oh Mrs Norris!" cried Mary, running towards her. "Thank God that you are here! You must help me — I think Edmund has taken poison — he must have despaired in the face of — but no matter — I fear I am not making myself very clear, but this is exactly what happened with poor Julia — we must act quickly — it may already be too late!"

Mrs Norris looked at her for a long moment, then shut the door quietly behind her.

"You would do better to sit down and calm yourself, Miss Crawford. These theatrical performances of yours serve no useful purpose."

"But — did you not hear me?" she stammered. "Your son has taken poison — we must procure him an emetic — I know what to do — and with your knowledge of remedies you must have such a thing in the house — there is a chance — if we intervene at once that we may — "

"We may what, Miss Crawford? Preserve his life so that you may tighten your grip yet further on his heart?"

"I do not know what you mean — "

"You were more than half to blame," she said, advancing towards Mary. "If it had not been for you, and that blackguard brother of yours, they would be married by now. Once Rushworth was out of the way I thought everything would return to how it should be, but oh no. Your contemptible brother resorted to the most vile arts, to the most depraved, wicked contrivances to lure her away — "

"But even if that were true," interrupted Mary, "it is not important now, not at this moment. We must act quickly to help Edmund or we will both lose him. Please, Mrs Norris — he has taken laudanum — a very great deal of laudanum — "

"I know exactly what he has taken, and I know better than you can do what the consequences will be."

Mary took a step back, hardly knowing what she did. It occurred to her, for the first time, that Mrs Norris did not look quite her usual self; there was an involuntary twitch under one eye, and she seemed to be labouring to catch her breath.

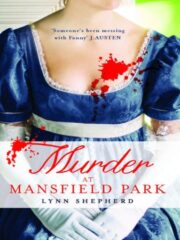

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.