"A pretty good lecture, upon my word!" said Henry, sarcastically. "Was it part of your last sermon?"

"Come, come," said Mrs Grant, quickly, "I am sure Henry is well aware that he has a good deal to answer for. I must say," she continued with a sigh, "I never thought to hear myself say such a thing, but it’s Mrs Norris I pity. I cannot imagine what she must be suffering."

"She will have to bear much worse if he is convicted," said Dr Grant. "As a gentleman, Norris might hope to avoid being dragged through the public streets to the taunts of the mob, but birth and fortune will not preserve him from the gallows. He deserves no better, and should expect no less; it will be a meritorious retribution for a crime so obnoxious to the laws of God and man."

Mary could endure no more, and leaping from her chair, ran out of the room. It was one thing to act as she had done, from the heroism of principle, and a determination to do her duty; it was quite another to hear Edmund’s fate so freely, so coolly canvassed. She took refuge in a far corner of the garden, which offered no view of the Park, feeling the tears running down her cheeks, without being at any trouble to check them. It was some minutes before she heard the sound of footsteps, and looked up to see her brother walking towards her.

As soon as he reached her, he took her hand, and pressed it kindly. "I am no great admirer of our brother-in-law, but you must forgive him, if you can, on this occasion. I do not think he has the least idea of your feelings for Mr Norris. Whatever our sister says, I believe you are more to be pitied than his unspeakable mother."

Mary nodded, a spasm in her throat. "It must have been the work of a moment — a temporary insanity — under sudden and terrible distress of mind — "

Henry looked away, uncomfortable.

"What is it, Henry?" she cried, catching his arm. "Tell me, please."

She would not be denied, and he did, at length, capitulate. "Very well. It was not, perhaps, so unpremeditated an act as you have just described. I have not told you this before, as there seemed no necessity to do so, but when we were in Portman-square, Fanny wrote to Mr Norris, to tell him of her marriage. I heard her give the messenger the directions to the White House."

"And what did she say in this letter?"

"I did not see it all, only some scraps. What I did see was couched in the scornful and imperious language that I was, by then, coming to expect from her. I do, however, recall one phrase. It was something to the effect that “I wonder now if my fortune was always the principal attraction on your part, given that I have now discovered that you are very much in need of it”."

"I do not understand — Edmund has an extensive property."

"Not, perhaps, as extensive as we have all been induced to believe. And it seems that this is not the only matter about which Mr Norris has dissembled. Having received that letter, he would have known that Fanny was married, but he said nothing of this to anyone at the Park."

Mary’s heart sank still further. "I suppose no killer would willingly draw such attention upon himself."

Henry pressed her hand once more. "But he has, at least, confessed. That can only assist him at the assizes. We must hope for clemency." He stopped, seeing the expression on her face. "Mary?"

She took a deep breath, and looked him in the eyes. "He did confess, but not voluntarily. I myself forced his hand."

She had, until that moment, adhered to Maddox’s request to keep the manner of Julia Bertram’s death a secret, but she saw no reason to respect his wishes any further, now that he had apprehended his killer. She saw at once that her brother was shocked and disgusted at what she had to tell him, far more shocked and disgusted, indeed, than he had been at the death of his own wife.

"But she was a mere child — an innocent child — "

"I know, I know — but if she did indeed see what happened that day — if he feared she was recovering and would soon tell what she knew — "

Henry dropped her hand and walked away, pacing across the grass, his face intent and thoughtful.

"Did you hear what our sister said, Mary? There was no mention, as far as I can recall, that Mr Norris has confessed to killing Julia. Fanny, yes, but not Julia. That is curious, is it not?"

It had not occurred to her before, and she hardly knew how to explain it. "I cannot tell, Henry, nothing seems to make sense."

"But this, indeed, does not make sense. From what you say, aside from good Mrs Baddeley, no-one at the Park is aware how Julia died — with one exception: our friend Maddox. So why has he not confronted Mr Norris with that fact? Why has he not extorted a second confession?"

Mary looked helpless."I do not know. It is unaccountable."

Henry was still pacing, still pensive. It was some minutes before he spoke again, but when he did, his words made every nerve in her body thrill with transport. "Do you really believe him to be guilty of these terrible crimes?"

"I do not want to believe it, but what choice do I have? I heard what Julia Bertram said."

"But from what you say, she only cried out his name — that does not prove anything in itself. Is it at all possible, do you think, that she was calling to him for help? We know he was in the park at that time. Might she have seen him at a distance, and called to him, even if he never heard her — even if he never even knew she was there?"

"Then why has he confessed? Why admit to a crime he did not commit?"

Henry took her hands in both his own. "Has it crossed your mind, even for the briefest of moments, that he may have been protecting you?"

"But why? Why should I need his protection?"

"Come and sit down, and tell me, as exactly as you can, what you said to Mr Norris this morning."

She sat down heavily on the bench, her mind all disorder, trying to recapture her precise words. "I–I told him that Julia had spoken a name, but that I did not need to repeat it. I said I could not allow you to be falsely accused, and that I had no choice but to go to Maddox. And I said," her voice sinking, "that he and I might never see each other again."

She was by now crying bitterly, but her brother, by contrast, was in a state of excited agitation.

"So you never, at any point, accused him directly?"

She shook her head.

"In fact, my dear Mary," he said, coming to her side and taking her hand, "everything you said might have led him to believe that you were confessing to him."

It was gently spoken, but every word had the force of a heavy blow. She gazed at him in amazement, her mind torn between bewilderment and mortification. The shock of conviction was almost as agonising as it was longed for; he was not guilty, but he was willing to appear so for her sake, and she alone had placed him in this peril.

"But Henry, this is dreadful!" she cried. "I must explain — how could he have believed me capable of — "

"You believed him capable, did you not?"

"I must go to him — to Maddox — I must tell him — "

"Calm yourself, my dear sister. You are not thinking clearly. We do not even know where Mr Norris is at this moment. He may, even now, be on his way to Northampton. And as for Mr Maddox, I fear you will need more proof than this to convince a man of his make. He has his reward money already in his sights, and he will not relinquish a suspect who has so conveniently confessed, unless we can present him with another equally promising quarry. Our best course will be to convince Mr Norris that his heroic concern for you is not necessary; if he can be persuaded to withdraw his confession, we may be better placed to counter Maddox."

"But how are we to do such a thing? If we do not even know where he is?"

"Leave that to me, my dear Mary. I will go at once to the Park, and see what I may discover. I do not expect the family to see me — that would be too much of an intrusion — but the steward, McGregor, will be as well-informed as any body, and he still has regard for me, even if some others at the Park do not. You, in the mean time, should take some rest. I will return as soon as I am able."

She had no better plan to propose, and returned to the house after watching him mount his horse, and head down the drive. She heartily wished to avoid going into company, but she knew that any further absence would only attract more notice and enquiry, so instead of retiring to her room she joined her sister and Dr Grant in the parlour. She could not hope for restraint from her sister, in the face of such extraordinary news, but she did hope that, by suggesting a game of cribbage before dinner, she might limit the scope of her speculations. The cards were brought, and for the next hour the reckonings of the game were interspersed with Mrs Grant’s wondering conjectures.

"And that makes thirty-one, Mary. And to think, all this time the killer was right under our very noses — and for it to be Mr Norris too! — it just shews that you can never judge by appearances — I always thought him such a placid and agreeable gentleman! Four in hand and eight in crib. And to think, anyone of us might have fallen prey to his murderous urges, and been slaughtered in our beds at any moment!"

"I think that most improbable, my dear," said Dr Grant, looking up from his copy of Fordyce’s Sermons. "According to the eminent authorities on the subject whose works I have perused, Norris does not exhibit any of the recognised characteristics of lunacy, and is therefore most unlikely to be an indiscriminate killer of the type to which you refer."

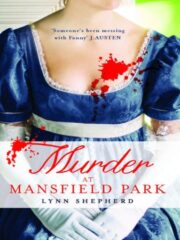

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.