As soon as the servants were awake she sent a message to the Park, requesting an interview at the belvedere that morning, then made a hasty breakfast, and went out into the garden.

By the time she heard the great clock at Mansfield chime nine, she had been waiting at the appointed place for more than an hour, and the bench offering an uninterrupted view to the house, she was able to watch him approaching for some moments, before he was aware of her presence. His step, she saw, was measured, and his comportment upright. When she rose to her feet and walked to meet him, she perceived, with a pang, that his step quickened.

"Good morning, Miss Crawford."

"Mr Norris."

"I must thank you, once more," he continued, "for the kind service you have afforded my family at this sad time. I have heard from Mrs Baddeley of your exertions in the last stages of Julia’s illness, and I know that you did all in your power to nurse her back to health. We are all, as you might imagine, quite overcome. To lose a daughter and a sister in such terrible circumstances, and so soon after the death of her cousin, it is — well, it is intolerable. My poor uncle will come home only to preside at a double funeral, though his presence will, at least, be an indescribable comfort to my aunt. We expect him in a few days."

There was a silence, and he perceived, for the first time, that she had not met his gaze.

"Miss Crawford? Are you quite well?"

"I am very tired, Mr Norris. I will, if you permit, sit down for a few minutes."

They walked back, without speaking, to the bench, too preoccupied by their different thoughts to notice a figure in the shadows, just beyond the wall of the belvedere, listening intently to every word they spoke.

Mary took her seat, and was silent a moment, endeavouring to quiet the beating of her heart.

"I have dreaded this moment, Mr Norris, and more than once I felt my courage would fail me before I came face to face with you. Now that I am here, I beg you will hear me out. I asked to see you because there is something I must tell you. It relates to your cousin."

He frowned a little at this, but said nothing.

"Some hours before Julia lapsed into her final lethargy, she became very distraught, and began to talk wildly. I did not perceive, at first, what had distressed her to such a dreadful extent, but I am afraid it soon became only too clear. As you know, she was walking in the park the day Miss Price returned; I now know that she saw something that morning, and she was frightened half out of her wits by the memory of it. I believe, in fact, that she saw quite clearly who it was who struck her cousin the fatal blow. She was talking incoherently about the blood — on her face, on her hands. It must have been a barbarous thing for such a young and delicate girl to witness."

She rose from her seat and walked forward a few paces, unable to look at him; she had hardly the strength to speak, and knew that if she did not say what she must at that very moment, she might never be able to do so.

"She — she — mentioned a name. I am sure you do not need me to repeat it. It is — too painful; for you to hear, or for me to utter. I only tell you this now because I am convinced that Mr Maddox is about to arrest my brother for this crime. I, alone of everyone at Mansfield, know that he absolutely did not do this thing of which he will be accused. I therefore have no choice but to go to Mr Maddox and tell him what I have just told you. Once I have done so, you and I will probably have no opportunity to speak; indeed," she said, in a broken accent, "we may never see each other again."

Had Mary been able to turn towards him and encounter his eye, she would have seen in his face such agony of soul, such a confusion of contradictory emotions, as would have filled her with compassion, however oppressed she was by quite other feelings at that moment. He rose and moved towards her, and made as if to put a hand on her shoulder, but checked himself, and turned away.

"I am grateful," he said in a voice devoid of expression, "for the information you have been so good as to impart. I wish you good morning."

He gave an awkward bow, and walked stiffly away.

She had enough self-control to restrain her tears until he was out of hearing, but when they came they were the bitterest tears she had ever had cause to shed. Notwithstanding Julia’s dying words, notwithstanding the seemingly incontestable nature of what Mary had heard, she had never entirely lost the hope that he might have an innocent explanation. That he would seize her hands, and tell her she was mistaken, that he was as blameless as her brother. But he had not. She had not seen him for some days, and in that time her knowledge of his character had undergone so material a change, as to make her doubt her own judgment. How could she have been in love with such a man — how could she justify an affection that was not only passionate, but also, as she had thought, rational, kindled as it had been by his modesty, gentleness, benevolence, and steadiness of mind? She must henceforth regard him as a man capable of murder, a man who could kill the woman to whom he was betrothed in the most brutal manner, without any apparent sign of remorse. And even if it were possible for her heart to acquit him, in some measure, of the death of Fanny, on the grounds of a sudden wild anger, or insupportable provocation, how could she ever forgive him for the part he had played in Julia’s demise — a gentle, sweet-tempered girl for whom he had appeared to feel deep and genuine affection? And when she had confronted him with the evidence of his guilt he had merely reverted to the cold and impenetrable reserve that had characterised their first acquaintance.

She wondered now whether Henry’s estimation of him had not been correct all along, and she had seen in Edmund something she had wished to see, but which bore little relation to his true character. And much as she had tried to dismiss it, she had never fully rid herself of a slight but insistent unease she had felt ever since the dreadful day when they had discovered Fanny’s body. Even in the midst of her terror she had thought his behaviour singular: she had told herself since, that his composure was that of a rational man, undaunted by the horrors of death, and concerned only to alleviate her own distress; but now she knew, beyond question, that it was not so: he had known all along what he would find in that trench, and prepared himself, however unconsciously, to behold it without recoiling. And yet she could not entirely quell the bewitching conviction that he had loved her, nor forget how she had felt with his eyes upon her. Whatever his fate, whatever his crime, she could not imagine thinking of another man as a husband. Was it an attachment to govern her whole life?

It was enough to shake the experience of twenty. And though she knew it to be her duty to go at once to Maddox and put an end to this suspense, she did not yet feel capable of such an irrevocable deed, and sought the most retired and unfrequented areas of the park, hoping by prayer and reflection to calm her mind, and steel herself against the final act of absolute condemnation. It was near the hour of luncheon when she returned to the parsonage, and she was in hopes that her walk in the fresh air had sufficed to wipe away every outward memento of what she had undergone since she was last within its doors. But she need not have been uneasy. Her sister came running towards her, as she entered the garden gate, her handkerchief in her hand, and her face in a high colour.

"Oh Mary, Mary! Such news, such shocking news! Mr Norris has confessed! He has told Mr Maddox that he killed Fanny! Who would have believed such a frightful and incredible thing?"

Mary was not quite so unprepared for this intelligence as her sister might have supposed, but it was not without its effect; she staggered, and felt she might faint, and a moment later felt Henry’s arm about her waist, supporting her.

"Come Mary," he said softly. "This is a most dreadful shock, and you have already had too much to bear. Come inside, and I will send for some tea."

She did not have the energy to refuse, and a few minutes later found herself sitting by the parlour fire, with her sister fussing about her, chattering all the while about the astonishing developments at the Park.

"Mrs Baddeley told me about it herself, when I encountered her in the lane. It appears Mr Norris went to Mr Maddox this very morning, and told him the whole appalling tale — how he met Miss Price that morning by accident, and they had the most terrible quarrel. He claims he never intended to harm her, but when she told him she was married, he was seized of a sudden by a desperate anger. It seems he does not remember much of what ensued, and it was not until the body was found, that it was brought home to him exactly what he had done."

"That being the case," said Dr Grant heavily, "it is a pity he did not make his confession then and there, and save us all a world of trouble and scandal."

"He has saved my neck, at least," said Henry. "I owe him a debt of gratitude for that."

"You, sir," replied Dr Grant, "have almost as much cause for remorse and repentance as Mr Norris can have. You, sir, deserve, if not the gallows, then the public punishment of utter disgrace, for your own part in this infamous affair. You, sir, have indulged in thoughtless selfishness, and coldhearted vanity for far too long. You, sir, would do better to take this unhappy event as a dire warning of what God apportions to the wicked, and hope by sincere amendment and reform, to avoid a juster appointment hereafter."

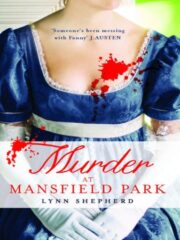

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.