" — she would not be able to prove the blood was her own."

"Quite so. She bribed her maid to keep her silence. Had she trusted me from the start, I would not have been forced to such disagreeable measures."

"Can you blame her, Mr Maddox? Your methods and demeanour hardly inspire confidence."

He inclined his head. "You may be right; I do not court popularity. But whatever the rights and wrongs of my means, the end is always the same: the truth. I know now that Maria Bertram did not kill her cousin, just as I know she did not kill her sister. Julia Bertram did not die because she heard or saw something at Compton, but because she heard or saw something at Mansfield Park, on the day of Mrs Crawford’s death. something or someone."

Maddox saw his companion grow yet paler at these words, but he said nothing. Many things might have provoked such a reaction, particularly in her current nervous state; nonetheless, he still felt sure that this young woman had a part to play in elucidating this crime, even if she would neither help nor trust him in his own efforts to do so.

They sat for a while in silence, a silence that was merely accidental on her part, but had been calculated with some exactness on his. It interested him to try whether she, a mere woman, could bear the oppression of silence longer than her brother, and his respect for her only increased when it became clear that, although there must be questions she wished to ask him, she could hold her tongue longer than many a vice-bitten London felon he had known. He stored away the insight for future perusal, shrewd enough to know that such a degree of self-composure was not only rare, but, at least in one respect, a rather ambivalent quality in any person caught up in the investigation of such a crime. At length, he spoke again. "I do not need to ask you if you saw someone tamper with the cordial. If you had, I am sure you would have informed me already. And if you had tampered with it yourself, you are hardly likely to confess it to me now."

She looked at him briefly, then resumed her contemplation of Dr Grant’s garden. "I will not dignify that remark by addressing it. Anyone in the house might have entered that room without arousing suspicion. Nor was it a crime that required undue premeditation. There was a vial of laudanum among the other medicines. It would have been the work of a moment to pour the contents into the cordial."

"I see that you have given the matter some thought, Miss Crawford.Your ratiocination is admirable."

"I deserve no compliments, Mr Maddox," she said, tears filling her eyes. "I will never forgive myself for not perceiving it sooner. The odour was palpable. You recognised it at once."

"I was looking for it; you, on the other hand, had no reason to suspect it. You were fatigued with watching, and anxious for your friend. Do not blame yourself."

"That is easily said, sir."

"Quite so." There was a pause, then he continued, "Given how closely you have examined the question, Miss Crawford, I am sure it has occurred to you to wonder when, exactly, the lethal dose could have been added to the cordial. Judging by the quantity remaining, it must have been but lately opened?"

"I gave the first dose from it myself, yesterday afternoon."

He saw the look on her face as she spoke, and when he resumed it was in a gentler tone. "I had presumed as much. In my experience, it would have been a matter of some hours only before the symptoms became unmistakable. And the bottle itself was not sealed?"

"No. None of them are. I dare say Mr Gilbert does not consider it necessary. It was only a cordial, after all."

"Was, yes. Quite so."

She looked at him for a moment, but said nothing. Maddox sat back in his seat. "We have made some progress, but not, as yet, advanced very far. As you yourself said, Miss Crawford, anyone in the house might have committed this crime; moreover, the same reasoning appertains to anyone who has entered the house since the bottle was left there."

She turned to him quickly, then looked away. Maddox continued, "I have had word from Gilbert. He says he left that bottle by Miss Julia’s bed two afternoons ago. He left it there, indeed, only a few short hours before Mr Crawford returned from his long absence, and hastened to pay his visit to the Park."

"Oh, you need not concern yourself about my brother, Mr Maddox. He did not remain in the house long enough, and was certainly not alone." She smiled, but it seemed to Maddox that she was struggling to maintain a corresponding lightness of tone, an effort somewhat belied by the slight flush to her cheek.

"On the contrary," he said, "I recall that Mr Bertram kept him waiting upwards of half an hour. A petty gesture, I grant, but perhaps we might forgive him, when we consider the injuries the family has suffered at your brother’s hands. And as you said, only a few minutes ago, it would have been the work of a moment to slip up to Miss Julia’s chamber."

"Perhaps," she said, with enforced patience, "if he had known where he was going. Do you ask me to believe my brother to be acquainted with the whereabouts of the sleeping-rooms of the young ladies of the house? I doubt he has even been upstairs. It is a ridiculous theory."

Maddox was undeterred. "He might have made a shrewd guess, based on all those other great houses in which he has been employed, or he might simply have followed Mrs Baddeley, without her being at all aware of it. It is not quite so ridiculous a theory as you maintain, Miss Crawford. Indeed, I wondered at the time why Mr Crawford was so determined to pay his call that evening, late and dark as it was. It might have waited until the morning, might it not? But for reasons of his own, your brother insisted on presenting himself at the Park without delay. Having gone thus far, let me postulate a little further. Let us say that your brother returned to the Park some days earlier than he would have us believe, and that he encountered his wife, fresh off the coach from London. Let us say that they argued — argued so bitterly that he was moved to strike her. Faced with the full enormity of his crime, he flees the estate, but not without first perceiving Miss Julia in the park. He does not know what she has seen — or if she has indeed seen anything — but when he returns some days later, feigning to have arrived directly from Enfield, he discovers that this possible witness has been all this time unconscious. He has an unlooked-for opportunity to silence her for ever, and he seizes it. Without remorse."

There was no doubt of the colour in her cheeks now, but the reason for it was not entirely clear to him. It might be anger at his impertinence, but it might equally be fear of discovery. Ever since he had learned that Crawford was Miss Price’s abductor, he had been convinced that he was by far her most likely killer. Logic, observation, and experience all argued for it, and if it was indeed so, he had no doubt that this young woman was in her brother’s confidence; Crawford would have confessed everything to her on his return, even if she had not known of his plans for the elopement until after it had taken place. Indeed, Maddox could easily see Mary Crawford as far more than a mere confidante; he knew she had loved the girl, but she loved her brother more, and if Julia Bertram’s silence was the only means to save him from the gallows, then it was a price she would be prepared to pay. If there was a woman in existence, who would have the courage, the resolution, and the sang-froid to carry through such a crime, he could believe Miss Crawford to be that woman.

"I do not believe him capable of such a thing," she said at last, in a tone of utter dejection, as if all her strength were gone.

"You did not believe him capable of lying, and yet he did."

She turned to look at him, as he continued, "He lied to you about being at Sir Robert Ferrars’s estate — indeed, I believe he even wrote you a letter that he claimed to have sent from there, which can only have been designed to deceive you. And if that were not enough, he lied to you about his marriage. I am sorry to be the bearer of such news — believe me, or not, as you will, but it gives me no pleasure to tell you this. I have just this hour received word from Fraser in London. He has spoken to Mrs Jellett, the gentlewoman who keeps the lodgings in Portman-square, and it is not a pretty story she had to tell. There were vehement arguments almost from the day they moved in — arguments loud enough to wake the rest of the house, and to make Mrs Jellett apprehensive for the reputation of her establishment. And that, I am sorry to say, was not all. The day before Mr Crawford departed — without settling their bills — there was a quarrel of such ferocity that Mrs Jellett was constrained to call the constable. She saw the marks of violence with her own eyes. And yet he told me — as he no doubt told you — that they were happy."

He watched her for a moment, awaiting a response, but she kept her eyes fixed firmly ahead.

"All things considered, Miss Crawford," he said at last, "I believe my enquiries are nearing their conclusion. Having spoken to you, I am more and more confident of that. An event is imminent. Yes indeed, an event is imminent."

Henry did not return from his ride for some hours, and the shadows were lengthening across the parsonage lawn, when Mary at last heard the sound of a horse in the stable-yard. Her sister had tried in vain to induce her to come indoors and take some rest, and had only with the greatest reluctance been persuaded to return to the house. Mary walked to the archway that led from the drive to the yard, and stood watching Henry, as he dismounted. He had provided himself with a black coat and arm-band, and she saw at once, and with inexpressible pain, that the assumption of formal mourning appeared to have deprived him of his quick, light step, and the poised and confident air that had so distinguished him in the past; he seemed weary to his very soul, and when he looked up and saw her, she knew from his face that the same desperate weariness was also visible in her own.

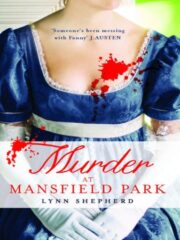

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.