"Please don’t say nothing, miss. That man Maddox is still in the house, and if he were to hear of it — "

"You have no need to fear, Polly," she said firmly. "I will see to that. But have you no idea at all what it was that Kitty told this man Fraser?"

Polly looked exceedingly awkward. "Not really, miss. Though I did hear her murmur something about — well, about Miss Julia."

Mary turned involuntarily to the figure lying unconscious on the bed; the girl had not, to Mary’s knowledge, spoken a word since the day she saw Fanny’s coffin carried past her room. But Julia? How could such an innocent young girl possibly be involved in this dreadful affair?

Mary sent Evans away with renewed promises of silence and complicity, and closing the door quietly behind her, sat down by the bed to ponder and deliberate. As the morning wore away, however, she was obliged to put her own concerns aside; she began to perceive that though Julia’s pulse had initially been much stronger, and her condition more favourable than on her preceding visit, she was slowly growing more heavy, restless, and uncomfortable. Mary asked for Mr Gilbert to be sent for, and waited anxiously until Mrs Baddeley ushered him into the room.

"I cannot comprehend it," he said, a few moments later, his face anxious, "every sign was growing more propitious, and I saw no cause to apprehend a relapse. Not, at least, a relapse such as this. You are sure — " this to Mrs Baddeley " — that only the cordials I prescribed have been administered, and in the correct doses?"

"I would stake my life on it, sir," said Mrs Baddeley, her pink face somewhat pinker than usual. "I have given the maids the most strict instructions."

Gilbert shook his head. "Only yesterday I was offering the family my felicitations on a recovery surpassing even my expectation, but now a recovery of any kind is most doubtful, most doubtful indeed. We will have to redouble our vigilance — and our prayers. Miss Crawford, can we prevail upon you to assist us yet further?"

Mary assured him of her complete willingness to watch the rest of the day, and the night if needed. It was a period of almost equal suffering to both. Hour after hour passed away in increasing pain and discomposure on Julia’s side, and in the most cruel anxiety on Mary’s, which could only be augmented by the new sense of unease that had arisen since her conversation with Evans.

She made a hasty dinner in the housekeeper’s room, and returned to relieve Mrs Baddeley. Julia was tossing to and fro, and uttering frequent but inarticulate sounds of complaint. Her face was flushed, and she seemed to be breathing with difficulty.

"I do so hate to see her in such a pitiable state, Miss Crawford," said Mrs Baddeley, with tears in her eyes. "I do believe she is worse even than when you went downstairs."

Mary put her hand on her arm, and offered words of reassurance that were very far from the forebodings in her own heart.

"Mr Gilbert has promised to call again in the course of the next three or four hours, Mrs Baddeley. Let us endeavour to support our hopes and spirits until then. We will be of more assistance to Miss Julia if we can remain calm."

At that moment Julia started up in the bed, and in a near frenzy, cried out, "No! No! It cannot be! It cannot be!"

Mary was at her side in an instant, and advising Mrs Baddeley to send for Mr Gilbert without delay, passed her hand over the girl’s brow.

"I am here, Julia. There is no cause for alarm. You are quite safe."

"No! No!" she moaned, "You must tell them — I can trust you — I did not mean — did not mean — an accident — an accident — "

"Hush, Julia, do not distress yourself so," Mary said imploringly, as she attempted to persuade her to lie down again, but when she clasped the girl’s shoulders, she felt her thin frame grow rigid against her.

"So much blood! — never knew — so much — her dress — her hands — never, never wished for that — let me be rid of it — let me forget it — never, oh never — no hope — no hope — "

She threw herself back on her pillows, as if exhausted, and lay for some moments neither moving nor stirring. Mary, too, was unmoving, half stupefied between horror and incredulity. Was this the explanation of the reprehensible conduct of Maddox and his associate? Was it indeed possible that Julia had been responsible, even if accidentally, for the death of her cousin? She knew the strength of her youthful passions, and the weak hold of more temperate counsels over the immoderation of youth and zeal; she knew, likewise, that Julia had been frantic to prevent the felling of the avenue, and in her high-wrought state, weakened by recent illness, the event had no doubt taken on a disproportionate enormity in her child-like mind.

As Mary sat retrospecting the whole of the affair, and the conversations she herself had witnessed, she began to perceive — all too late — that Julia might, indeed, have come to regard Fanny as wholly to blame for the disaster about to befall her beloved trees, believing her cousin could have prevented it, had she been prepared to intercede, and use her considerable influence to compel her uncle to alter his plans. Much as her heart revolted from the possibility, Mary’s imagination could easily conceive of a meeting between the two cousins in the park that ill-fated morning — the very morning that the work was due to commence. She could picture Fanny listening to her cousin’s pleas with contempt and ridicule, and Julia, provoked beyond endurance, striking out in desperation and fury, if only to put an end for ever to the scorn in that voice. She did not want to believe it, but her heart told her that it was possible, just as her mind acknowledged that it would explain many things that had puzzled her hitherto; it would render Julia’s despairing decision to chain herself to the trees more readily comprehensible; and it would account for her terror at the sight of her cousin’s coffin. Mary thought back to that dreadful scene, and recalled, with a cold shudder that carried irrefutable conviction, the actual words Julia had used. She saw her in imagination, standing in the door of her chamber, her hand to her mouth, crying out, "She is not dead, she cannot be dead." But how could she possibly have known whose coffin it was? The family had been careful to conceal the news of her cousin’s death from her.There was only one answer, only one explanation.

How Kitty Jeffries had come to discover the secret, Mary could not guess; all she did know, was that discover it she had, and Maddox had wrung it from her. Even now, she thought, he must be waiting only for Julia’s recovery to question and apprehend her, and she recalled with a tremor of sick dread her own brother’s words as to the fate that must inevitably attend the perpetrator of such a crime. She started up and began to pace the room, unable to keep her seat with any composure. She could see no way to obviate such terrible consequences, no other way to explicate what she had heard than by casting Julia — all unlikely as it seemed — in the repellent light of her cousin’s murderess.

She stopped by the window, and pulled aside the heavy curtain. It was moonlight, and all before her was solemn and lovely, clothed in the brilliancy of an unclouded summer night. She rested her face against the pane, and the sensation of the cool glass on her flushed cheeks made her suddenly aware how stifling the room had become. She went across to the door, flung it open, and stood for a moment on the threshold. The great house was still and noiseless — or was it? She knew her nerves were more than usually agitated, but she thought, for one fleeting instant, that she had detected a movement in the dark shadows, beyond the wan circle of light cast by the lamp. It was not the first time she had felt such a sensation in recent days, and she suspected Maddox was deploying his men as spies. Had Stornaway been deputed to listen at Julia’s door, and if he had, what had he heard?

She wavered for a moment, wondering whether to seek the man out, and challenge him, but a few minutes’ reflection told her that nothing she could do would make any difference, and whatever the man might have gathered by stealth, would no doubt only serve to confirm what his master had already obtained by violence. She returned into the room with an even heavier heart, and took her place once again at the bed-side. Julia had recommenced her feverish and confused murmurings, and Mary was so preoccupied, and so fatigued by her many hours of watching, that it was some moments before she discerned that the tenor of the girl’s ramblings had undergone a subtle but momentous change.

"I can never be free of it — never erase it — never blot it out — that face, those eyes — cannot bear it — pretend I never saw, pretend I never heard — no, no, do not look upon me — I will not tell! I will not tell!"

The precise import of these words forced itself slowly but inexorably upon Mary’s consciousness. It was not Julia who had killed Fanny, but someone else. Julia’s previous burst of feeling did not signify her own guilt, but her horror at having seen her own cousin being brutally done to death, and by someone she herself knew. It was no wonder the girl was distraught — no wonder she was in terror —

Mary’s heart leapt in hope — and as soon froze, as the girl sprang up suddenly in the bed, her lips white, and her eyes staring sightlessly across the room. "Do not look upon me! — I will not tell — a secret — always, always a secret! — Edmund — Edmund!"

Chapter 17

Charles Maddox was, at that moment, standing in silence on the garden terrace. He was not a man who required many hours of repose, and it had become his habit to spend much of the night watching, taking the advantage of peace and serenity to marshal his thoughts. Living as he did in the smoke and dirt of town, he could but rarely, as now, enjoy a moonlit landscape, and the contrast of a clear dark sky with the deep shade of woods. He gazed for a while at the constellations, picking out Arcturus and the Bear, as he had been taught as a boy, while reflecting that moonlight had practical as well as picturesque qualities: a messenger could ride all night in such conditions as this, and that being so, Maddox might, with luck, receive the information he required in the course of the following day. He had sent Fraser to London, to enquire at Portman-square as to the exact state of affairs between Mr and Mrs Crawford during their brief honeymoon; the husband had claimed they were happy, but every circumstance argued against it. Maddox had seen the clenched fist, the contracted brow, and the barely suppressed anger writ across his face. He would not be the first man Maddox had known, to conceal violent inclinations beneath a debonair and amiable demeanour, and this one had a motive as good as any of them: not love, or revenge, but money, and a great deal of it.

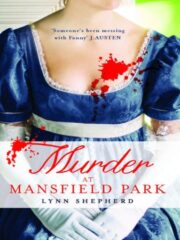

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.