"Come, Henry, sit with me by the fire."

He sat for some moments in silence, until prompted by her once more.

"Did you see the family — Mr Bertram, her ladyship?"

"I saw Maddox, mostly. He it was who has detained me so long. The man is a veritable terrier, Mary. Heaven help the guilty man who finds himself in his power, for he can expect no quarter there. Would to God that you had told me he knew so much of Enfield — he had all the facts at his fingers’ ends as if it had happened only yesterday. It was like living the whole atrocious business through a second time. I had thought we had left it behind us in London, and now it returns to haunt us once more — will we never be free of it?"

Mary put a hand on his arm. "I am sorry. I should have said something. But our sister and Dr Grant were in the room at the time, and we agreed never to speak of it to anyone. No good can come of doing so now. It would only — "

" — give my brother-in-law yet further reason to suspect me, and fix me even more firmly at the head of whatever list it is that Maddox is busily compiling. Good God, Mary, it appeared as if every word I uttered only made me seem the more guilty."

"Do not lose courage. If Mr Maddox is ruthless, that should only reassure us that he will, at the last, discover who really committed this crime."

Henry shook his head sadly. "I am afraid you do not appreciate how such a man Maddox is accustomed to operate. He will receive a fine fat reward for bringing the culprit to justice, but what will happen if he cannot find the real villain? Do you imagine he will merely doff his hat to Tom Bertram, and admit he has failed? Depend upon it, he will deliver someone to the gallows, and whether it is the right man or no will not trouble him unduly."

They sat in silence for a long while after this, until Mary ventured to ask him, once more, if he had seen the family.

"I saw Mrs Norris, who was intent on seeing me off the premises with all dispatch. I am heartily glad you were not there to see it — or hear it, given the choice turn of phrase she chose to avail herself of. The only thing that distinguishes that old harridan from a Billings-gate fishwife is a thick layer of bombazine, and a thin veneer of respectability. No, no, my conscience is easy on the score of Mrs Norris; she has never shewn me either consideration or respect, and I will requite her insolence and contempt in equal measure. But I do have cause for self-reproach on Lady Bertram’s account. You know I have always thought her a silly woman — a mere cipher — interested only in that vile pug and all that endless yardage of fringe, but she has a kind heart, for all that, and has borne a great deal of late, without the strength and guidance of Sir Thomas to assist her. I am afraid to say that this latest news has quite overcome her, and she has taken to her bed. I am heartily sorry for it, and all the more so since I discovered how ill Miss Julia had been these last few days."

"And the gentlemen — Mr Bertram?" and, this with a blush, "Mr Norris?"

"I saw Bertram very briefly. He left me kicking my heels for upwards of half an hour, but I had expected no extraordinary politeness, and suffered my punishment with as good a grace as I could, feeling all the while like a naughty if rather overgrown schoolboy. He was angry — very angry — but he neither called me out, nor threatened me with all the redress the law affords, which I confess, I had at times been apprehensive of, even though Fanny was of age and the marriage required the consent of neither parent nor guardian. I verily believe he did not know whether to address me as his cousin’s ravisher, her widowed husband, or her probable assassin. We none of us have the proper etiquette for such a situation as this. Norris did not appear at all, and I confess I was not sorry. I have had my fill of doleful and portentous prolixity for one day — indeed I often wonder if Norris has not missed his vocation. If Dr Grant should succeed to that stall in Westminster he endlessly prates of, our Mr Norris would make a capital replacement, and could hold forth in that pompous, conceited way of his every Sunday, to his heart’s content."

It was, for a moment, the Henry of old, and Mary was glad of it, even if it came at such a price; but her joy was short-lived.

"And besides," he said in a more serious tone, "I do not know what I should have said to him. My marriage has become a source of regret to me, Mary, and not least for the pain it has caused to others — a pain that I cannot, now, hope to redress."

He sighed, and she pressed his fingers once again in her own, "You must tell me if there is anything I can do."

"There is certainly something you can do — for the family, if not for me. Good Mrs Baddeley took me to one side as I departed, and begged me to ask you to go to the Park in the morning. It seems Miss Bertram is taken up with nursing her mother, and Miss Julia is still in need of constant attendance. Mrs Baddeley was high in her praise of you, my dear Mary, and I trust the rest of the family is equally recognisant. Indeed, I hope their righteous fury at the brother’s duplicity does not blind them to the true heart, and far more shining qualities, of the sister."

Mary’s eyes filled with tears; it was long since she had heard such tender words, or felt so comfortable in another’s company. Having been alone in the world from such an early age, the two had always relied on each other; her good sense balancing his exuberance, his spirits supporting hers; his pleasantness and gaiety seeing difficulties nowhere, her prudence and discretion ensuring that they had always lived within their means. She perceived on a sudden how much she had missed him, and how different the last weeks would have been had he been there. But it was a foolish thought: had Henry been at Mansfield, none of the events that had so oppressed her would ever have occurred.

"I will go, of course, but I meant to ask if there was anything I could do for you."

"Nothing, my dear Mary," he said, with a sad smile, "but to take yourself off to bed and get what sleep you can.You will need your strength on the morrow. Do not worry, I will be up myself soon."

He watched her go, and settled down into his chair, his eyes thoughtful; and when the maid came to make up the fire in the morning, that was where she found him; in the same chair, and the same position, hunched over a hearth that was long since cold.

Chapter 16

Nothing but the assurance that her presence was both necessary and wished for would have reconciled Mary to calling on the Bertrams, after such revelations as her brother’s return had precipitated, but she gathered her courage, and presented herself at the Park at an earlier hour than common visiting would warrant. Mrs Baddeley received her in a rapture of gratitude, and she was glad, for once, to encounter no-one but the housemaids on her way upstairs. She had soon installed herself by Julia’s bed-side, happy to feel herself useful, and knowing that she brought comfort to at least some of the inmates of Mansfield Park. The household was slow to stir that morning, and Mary was probably the only person, besides the servants, to observe the departure of George Fraser. Hearing sounds on the drive she had stepped to the window, to see him emerge from the house, carrying a knapsack of such a size and bulk as anticipated at least one night’s absence. She was watching him mount, when the door opened, and Julia’s maid entered with a pile of clean sheets for the bed. She saw Mary at the window, and stopped for a moment at her elbow.

"The footmen say he be heading towards London, and then to another place in the same direction. Some wheres beginning with N?"

"Enfield," said Mary, her heart sinking. "I imagine he is going to Enfield. My brother has a house there."

Evans’s eyes widened. "So it’s true, miss! Miss Fanny — she upped and went off with your Mr Crawford! I always did say he was a lovely-looking gen’leman. Always a smile for the likes of us — and a thank you, as well — you can’t say that for everyone who comes a-calling here."

The girl’s cheeks had, by now, grown very pink, and her eyes had strayed from Mary’s face. Mary sighed; she knew her brother occasionally indulged himself in harmless gallantries with maid-servants, but she had never approved of such careless conduct, and liked it even less when it concerned girls of Polly Evans’s youth and naiveté. She was wondering whether it was necessary to caution her, however gently, to be rather more guarded in future, when hooves sounded on the gravel, and Polly turned to the window once again, her pretty features darkening into a frown. "Let’s hope that’s the last we see of that evil villain — and fair riddance. Poor Kitty Jeffries hasn’t risen from her bed since he was set loose on her. She won’t eat, and sobs as if her heart would break."

Mary turned to her aghast. "What can you mean, Polly?"

Polly clapped her hand to her mouth. "Oh miss, I shouldn’t have said nothing! She made me promise on the Bible not to tell. That Maddox, he put the fear of God on her if she so much as breathed a word."

"But is she harmed — is she in need of a physician?"

Polly shook her head. "Not now. Mrs Baddeley took a look at her, and said there was nothing broke, and the marks would heal. Don’t fret, miss," she said, seeing Mary’s horrified look, "it’s no worse than what her pa used to do to her when he was angry and in drink. Kit’s a tough one — she’s used to it."

Mary felt for a chair, and sat down heavily, her mind in a tumult; what justification could there be for the use of such extremes of violence on a blameless servant? What could Maria Bertram’s maid possibly know that would force Maddox to resort to such desperate measures to extort it from her? She looked up at Evans, who was wringing her hands in a state of extreme agitation.

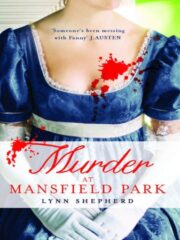

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.