Henry shook his head, his eyes cast down.

"At noon, then? Surely no later than three?"

Henry drained his glass. "I left the next day."

Both men were silent.

"There was no particular reason for this otherwise unaccountable delay?" said Maddox at last.

"No reason I am prepared to divulge to you, Mr Maddox. I do not choose to enlarge upon my private concerns. All I am willing to confirm is that I stayed two nights on the road at Enfield. That is all."

"No matter, Mr Crawford. I am happy to take the word of your grooms and coachman. Unless, of course, you came on horseback?"

He had not needed to ask the question to obtain the answer; and it had not exercised any great intellectual faculty to do so: his companion was in riding-dress, and the hem of his great-coat was six inches deep in mud. The facts were not in dispute; he only wished to see how Crawford addressed them, and on this occasion it was with some self-possession.

"To use your own phrase, Mr Maddox," he replied, with a scornful lift of the brow, "I would expect a man in your line of work to have taken notice of my boots."

Maddox inclined his head. "Quite so, Mr Crawford, quite so." Had he known it, he had just had a glimpse of another Henry Crawford, the witty and charming Henry Crawford who had succeeded in persuading one of the country’s foremost heiresses to elope with him. Maddox smiled, but never had his smile been more artificial, nor his eyes more cold than when he next spoke.

"You were, I believe, examined by the constables after the death of your housekeeper."

It took a moment for the full implications of the question to be felt.

"You are well informed, sir," Henry said at last, in a purposely even tone. "And that being the case, you will also know that they were more than satisfied with the information I was able to impart. After all, what possible reason could I have had for committing such a repugnant crime?"

"None at all, I grant. Though the present case is somewhat different, is it not? You would, I contend, have every possible reason to murder Mrs Crawford.You will now take full possession of a very considerable fortune, without the concomitant inconvenience of a demanding, and from what I hear, rather unpleasant wife."

Henry flushed a deep red. "I will not allow you, or any man, to insult her. Not before my face. I loved her, sir."

"Perhaps you did; perhaps you did not. That does not materially alter the facts. Nor does it explain why you tarried two days in an empty house when you claim you were desperate to find her."

"I have already addressed this. I told you — it is none of your concern. And besides, I hardly knew what reception I might expect when I did arrive. I was not certain how the family would receive the news."

Maddox adopted an indulgent tone. "Come, come, Mr Crawford, you are disingenuous. I am sure you knew perfectly well how the Bertrams would view such a marriage. To see Miss Price’s fortune pass out of the family, and in such a fashion! So shortly before the union that had been planned for so long, and was so near consummation! Mrs Norris may not, I own, be a fair sample of the whole family," he continued, as Henry shifted uncomfortably in his chair, "but did you really imagine Sir Thomas would embrace you with rapture, and congratulate himself on the acquisition of such a nephew? But we digress. Let us return for a moment to the unfortunate Mrs Tranter."

Henry leapt to his feet and paced to the farther end of the room, before turning to face Maddox. "Must you continually harp on that string? It has nothing whatever to do with what happened to Fanny. It is nothing but an unlucky coincidence."

"That may, indeed, be one explanation. But there are some noteworthy similarities between the two cases, I think you will find. Not least the extreme and unnecessary violence with which each attack was perpetrated."

"True or not, that has nothing whatever to do with me. What possible reason could I have had for murdering the unlucky creature? She was a mere servant, nothing more."

"There, I am afraid, we disagree. Hetty Tranter was far more than a mere servant, at least as far as you were concerned. Indeed, it is quite alarming how often the women you seduce meet their deaths in such a cruel and brutal fashion."

Crawford turned away. "I do not know to what you refer."

"Come, Mr Crawford, we are both men of the world. This Hetty Tranter was your mistress. Oh, there is little point in denying it — your countenance has already betrayed you. Indeed, you may have papered over your debaucheries by calling her your "housekeeper", but the real truth is that you had installed this girl in the Enfield house for your own sordid convenience. At a discreet distance from town, far from the prying eyes of your loftier acquaintances, and the rather juster remonstrances of your sister. She is still in ignorance of this particular aspect of the affair, is she not?"

"And I had rather she remained so," said Crawford quickly — too quickly, as the expression on his companion’s face immediately testified.

Maddox nodded. "I can see that it would, indeed, be most trying to have to explain your squalid depravities to someone as principled as Miss Crawford. So trying, in fact, that you might well have been tempted to silence the Tranter girl once and for all — especially if she were becoming importunate in her demands. Or if, shall we say, she had told you she was with child, or threatened to expose you to your sister. Or even, poor wretch, if you had merely tired of her, and wished to rid yourself of an incumbrance which had, by then, become nothing more than a source of irritation."

Crawford’s face had turned very red. "How dare you presume to address me in this manner — there is absolutely nothing to substantiate a single one of these vile and disgusting accusations, and I defy you to do so."

Maddox remained perfectly calm. "You are quite right. If there were such proof, no doubt even the rather slow-witted constables of the parish of Enfield might have been expected to uncover it."

Crawford took a step nearer. "And if I find you repeating any of these base and unfounded allegations to my sister — "

He had, by now, approached so close as to be less than a foot from the thief-taker, but Maddox stood his ground, even in the face of such encroachment. "I have no wish to distress her, sir. Unless, of course, it is absolutely necessary. I am sure that she — like you — would prefer to forget the whole horrible affair; but unlike you, she may one day be successful in that endeavour."

"And what do you mean to insinuate by that?"

"Merely that unresolved murders of this kind have a habit of coming to light, even after the lapse of several years. The law may seem to nod, Mr Crawford, but she is not wholly blind, especially where unanswered questions persist, and when the persons involved subsequently find themselves entangled in circumstances of a similar gruesome nature. It is interesting, is it not, that then, as now, you cannot confirm your whereabouts at the time of the killing?"

Crawford turned away, and Maddox watched with interest as his companion perceived, for the first time since he had entered that room, that he was face to face with his dead wife. Maddox had wondered, when he elected to use Sir Thomas’s room for this interview, whether Crawford had ever entered it, or seen this portrait, and now he had his answer. It was, he believed, a striking likeness of the late Mrs Crawford. The painter had no doubt yielded to the young lady’s demands as to the pink satin gown, the bowl of summer roses, and the small white dog leaping in her lap, but he was evidently a good hand at drawing a likeness, and there was a certain quality in the set of her head, and the curl of her lip, that belied the outward charm and sweetness of the tout ensemble.

Crawford was still standing before the portrait, lost in thought. He seemed to have forgotten the presence of his interlocutor; it was the very state of mind that Maddox had hoped to induce, and too fair an opportunity for a man of his stamp to let pass.

"I wonder, did the constables ever resolve the mystery of the shirt?"

Henry turned slowly, his countenance distracted.

"If you recall, Mr Crawford," continued Maddox, "the hammer with which Mrs Tranter was so cruelly done to death was subsequently discovered in the garden of the house, wrapped about in a blood-stained shirt." He paused. "Her blood, but your shirt."

Henry shook his head, as if to banish the thoughts that had begun to beset him. "It was an old shirt," he said. "One I had deposited in a trunk in the house. I cannot explain how the ruffians came to discover it."

"Any more than you can explain why a witness claimed to have seen you in the neighbourhood that day? A washerwoman, was it not?"

"She was mistaken, God damn you! She was old, half-blind and very likely in liquor. She was mistaken. Indeed, as I recall, she withdrew her story only a few days later."

"So there is no danger of a similar sighting in the vicinity of Mansfield on the day your wife was battered to death?"

Henry Crawford’s face, which had been flushed, was now as pale as ashes. "Absolutely none. I was, as I said, still in London.You may make whatever enquiries you choose."

Maddox drained his own glass, and placed it carefully on the table. "Thank you, Mr Crawford. I would have done as much whether you consented or not, but this is a rather more civilised way of proceeding, is it not?"

Mary was alone in the parlour when Henry returned. The impetuous and defiant demeanour had gone, and been replaced by an expression she might almost have called fear. As she handed him a glass of Madeira she noticed that his hands were cold, even though the evening was warm.

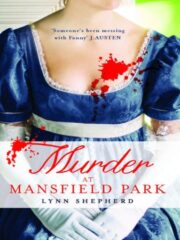

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.