"May I be of some assistance, Mrs Norris?" said Maddox, with a bow. "And perhaps you might do me the honour of introducing me to this gentleman."

"There will be no call for that," said Mrs Norris quickly. "And I can assure you, he is not a gentleman. Indeed I cannot think what Mr Crawford is doing here, unless it be to enquire what we intend to do about the improvements. The time is not convenient, sir. We cannot stay dinner to satisfy the importunate demands of a hired hand. I suggest you call on the steward in the morning."

"So this," mused Maddox, "is the Henry Crawford of whom I have heard so much." His person and countenance were equal to what his imagination might have drawn, but Maddox had been in Mary Crawford’s company sufficiently often to make a tolerable guess as to the number of her gowns, and the constraints on her purse. He had not expected a brother of hers to have the means to equip himself so handsomely; an idea was forming in his mind, and he began to have a faint glimmering of suspicion as to what was to ensue.

"Forgive the intrusion at this late hour," said Henry, "but am I correct in supposing that I am addressing Mr Charles Maddox? I am but recently arrived at the parsonage, and have only now been informed about — "

"We have no need of your sympathy, Mr Crawford," said Mrs Norris, drawing herself up more stiffly than ever. "Who knows, or cares, for what you have to say? The death of Miss Price is a private family affair, and can have nothing whatsoever to do with such as you."

"I beg to differ, madam," said Henry, coldly. "I rode up here directly, as soon as I heard the news. It became absolutely necessary that you should all know the full truth, and from my own lips."

"What truth, sir?" demanded Mrs Norris, peremptorily.

"The truth that Fanny — "

"Fanny? Fanny?" she gasped. "By what right, sir, do you dare to call Miss Price by her Christian name?"

Henry stood his ground, and did not flinch. "The best right in the world, madam. A husband’s right."

There was a instant of terrible silence, then she threw up her hands before her face, uttered a piercing shriek, and sank down prostrate on the floor. Maddox had anticipated the revelation by some moments, and knowing something of Mrs Norris, and conjecturing pretty well what a blow this must be to the family’s pride and repute, he feared that she might succumb to a fit. But Mrs Norris had a strong constitution, and quickly found a vent for her fury and indignation in a vehement bout of crying, scolding, cursing, and abuse.

"You are a scoundrel," she screamed, pointing her finger in Henry’s face, "a felon — a lying, despicable blackguard — the most infamous and depraved villain that ever debauched innocence and virtue — "

This invective being interspersed by screams so loud as must soon alarm the whole house, Maddox made haste to lift Mrs Norris to her feet, and turning to the butler, interposed with all necessary authority, "I think, Baddeley, that Mrs Norris would benefit from a glass of water and some moments lying down; perhaps the footmen might attend her to the parlour? See that her ladyship’s maid is called, and inform Mr Bertram and Mr Norris, if you would be so good, that I will beg some minutes’ conversation with them after dinner. I will be with Mr Crawford in Sir Thomas’s room."

The door closed and peace restored, Maddox poured two glasses of wine, and handed one to his companion, noting, without surprise, that he held it in his right hand. He then took up a position with his back to the fire. Crawford was standing at the French windows, looking out across the park; the sky was beginning to darken, but it would still be possible for him to make out the alterations that had already been imposed on the landscape at his behest; the transformation about to be wrought inside the house might prove to be even more momentous. Maddox wondered how long it would be before the news of Miss Price’s scandalous marriage had spread throughout the whole household, and made a wager with himself that the last and least of the housemaids would know the whole sorry story long before most of the family had the first notion of the truth about to burst upon them. He wondered, likewise, whether he might now be on the point of elucidating this unfortunate affair, but abstained from assailing his companion with questions, however much he wished to do so. He had long since learned the power of silence, and knew that most men would hurry to fill such a void, rather than allow it to prolong to the point of discomfiture. He was not mistaken; Henry Crawford stood the trial longer than most men Maddox had known in his position, but it was he who broke the silence at last.

"You will expect me to be particular."

Maddox took out his snuff-box and tapped it against the mantel. "Naturally. If you would be so good."

"Very well," Crawford said steadily, taking a seat before the fire. "I will be as meticulous as possible."

He was as good as his word. It was more than half an hour before he concluded his narration; from the first meeting in the garden, to the hiring of the carriage, the nights on the road as man and wife, the taking of the lodgings in Portman-square, and the wedding at St Mary Le Bone, on a bright sunny morning barely two weeks before.

"So what occurred thereafter?" said Maddox, after a pause. "Listening to what you say, one would be led to expect this story to have a happy ending, however inauspicious its commencement. How came it that Mrs Crawford returned here alone?"

Henry got to his feet, and began to pace about the room.

"I have already endeavoured to explain this once today, but to no avail. The simple answer is that I do not know. I woke one morning to find her gone. There was no note, no explanation, no indication as to her intentions."

"And when, precisely, was this?"

"A week ago. To the day."

"I see," said Maddox thoughtfully. "But what I do not at present see, is why — given that Mrs Crawford arrived here so soon thereafter — you yourself have not seen fit to make an appearance before now."

"I had no conception that she would choose to return here, of all places. She abominated this house, and despised most of the people in it. To be frank with you, sir, I find it utterly incomprehensible."

Maddox took a pinch of snuff, and held his companion’s gaze for a moment. "May I ask what you have been doing, in the intervening period?"

Henry threw himself once again into his chair, and Maddox took note that, consciously or not, Crawford had elected a posture that obviated any need for him to meet his questioner’s eye, unless he actively wished to do so.

"I have been searching for her," he said, with a frown. "I spent two fruitless days scouring London, before resorting to the dispatch of messengers to Bath and Brighton, and any other place of pleasure that might have offered her similar novelty or enlargement of society. She did not lack money, and could have taken the best house in town, wherever she lighted upon. Nor would she have seen any necessity for the slightest discretion or subterfuge. I calculated that this fact alone would assist me in finding her. But it was hopeless. I could discover nothing."

"And you conducted these enquiries where, exactly?"

"From our lodgings in Portman-square."

"So I take it you come directly from London?"

Henry hesitated, and flushed slightly. "No. Not directly. I come from my house at Enfield."

Maddox looked at him more closely; this was an interesting development indeed. "Now that, sir, if you will forgive me, strikes me as rather odd. Capricious even."

"I do not see why," retorted Henry, sharply."I had decided to return to Mansfield, and Enfield is in the way from London."

"Quite so," said Maddox, with a smile. "I do not dispute your geography, Mr Crawford. But I do ask myself why a gentleman in your position — a man of means, with horses and grooms at his disposal, and the power to command the finest accommodations in the country — should voluntarily, nay almost wilfully, elect to lodge in a house that, as far as I am aware, is barely larger than the room in which we sit, and has not been inhabited for years. Not, indeed, since the regrettable death of poor Mrs Tranter."

Henry started up, and stared at his companion. "How do you come to know of that?"

Maddox’s countenance retained its expression of impenetrable calmness. "You will not be surprised to hear that your delightful sister asked me exactly the same question, Mr Crawford. But it was a brutal and notorious crime, was it not? And not so very far from London.You would surely expect a man in my line of work to have heard tell of such an incident. The gang was never apprehended, I collect."

Henry shook his head. "No, they were not."

Maddox turned to stir the fire. "I gather your sister finds the house so retentive of abhorrent memories that she will not set foot in it.You, by contrast, elect to stay under that very roof, when you might have had your pick of lodgings without stirring a finger."

He turned to face Crawford once more, but received no reply.

"But perhaps I am unjust," he continued. "Perhaps you found yourself in the immediate neighbourhood just as twilight descended. Perhaps it was easier to put up for the night there, than search for more suitable quarters after dark. And, after all, I have no doubt that you stayed not a minute longer than was absolutely necessary. You must have been in such haste to be gone that you left with the light the following morning. Am I right?"

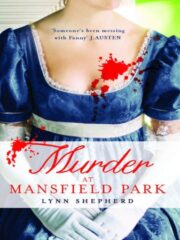

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.