He fell silent, and they heard the distant sound of the great clock at Mansfield, striking the half hour. Mary stirred in her chair. She hardly dared trust herself to speak, yet it was now absolutely necessary to do so. But even as she was collecting her thoughts and wondering how to begin, the door opened for a second time.

"You see, my dear," Dr Grant was saying to his wife as they came into the room, "I was quite right. I knew the presence of such a horse in the yard could betoken only one thing. I will see to it that more claret is brought up from the cellar. I am glad to see you again, Crawford, even if you do return to a neighbourhood in mourning. We will all be very thankful when Sir Thomas resumes his customary place at Mansfield, and the funeral can at last take place; so protracted a delay is disrespectful, and serves only to amplify what is already the most lamentable circumstance. Indeed, I cannot conceive a situation more deplorable."

"In mourning?" said Henry, rising again from his chair. "I do not understand — that is, Mary did not say — "

Mrs Grant looked first to Henry, and then to her sister. "Mary? Surely you have been most remiss — there has not been such an event as this in these parts for twenty years past. You will scarce believe it, Henry, but we have had a murder amongst us. Miss Price is dead."

Dr Grant was the only one among them capable of any rational thought or deliberation in the course of the extraordinary disclosures that must naturally follow, though Mary could have wished his remonstrances less rigorous, or at the very least, rather fewer in number. Dr Grant had, indeed, a great deal to say on the subject, and harangued Henry loudly and at length for having so requited Sir Thomas’s hospitality, so injured family peace, and so forfeited all entitlement to be considered a gentleman. Mrs Grant needed her salts more than once, during this interminable philippic; while Henry, by contrast, seemed hardly to hear a word of it. He was not accustomed to allow such slights on his honour to pass with impunity, even from his brother-in-law, but his manner was distracted, and his whole mind seemed to be taken up with the attempt to comprehend such an unspeakable turn of events; he had started that day a husband, even a bridegroom, but he would end it a widower.

Dr Grant had not yet concluded his diatribe. "And now we have this wretched man Maddox in our midst, poking and prying and intermeddling with affairs that in no way concern him, in what has so far proved to be a fruitless quest for the truth. He will want to see you, sir, without delay; that much is abundantly clear. There will be questions — and you will be required to answer. And what will you have to say for yourself, I wonder?"

There was a silence. Henry did not appear to be aware that he was being addressed. He was staring into the bottom of the glass of wine Mary had poured for him, his thoughts elsewhere.

Dr Grant cleared his throat loudly. "Well, sir? I am waiting."

Henry looked up, and Mary saw with apprehension that his eyes had taken on a wild look that she had seen in them once before, many years ago. It did not bode a happy issue.

"What did you say?" he cried, springing up and striding across the room towards Dr Grant. "Who is this — Maddox — you speak of? By what right does he presume to summon me — question me?"

The two men were, by now, scarcely a yard apart, and Henry’s face was flushed with anger, his fists clenched. Mary stepped forward quickly, and put a hand on his arm. "He is the person the family have charged with finding the man responsible for Fanny’s murder," she said. "It is only natural that he should wish to talk to you — once he knows what has occurred."

Henry shook her hand free; he was still staring at Dr Grant, who had started back with a look of alarm.

"Henry, Henry," said Mary, in a pleading tone, "you must see that it is only reasonable that Mr Maddox should wish to talk to you.You may be in possession of information that could be vital to his enquiries. You must remember that you saw her — spoke to her — more recently than any of us. It may be that there is something of which you alone are aware, which may be of vital significance — more than you can, at present, possibly perceive."

She stopped, breathless with agitation, and watched as Henry stared first at her, and then at her sister and Dr Grant.

"So that is what you are all thinking," he said, nodding slowly, his face grim. "You think I had something to do with this. You think I was responsible in some way for her death. I — her husband — the man she risked everything to run away with — you actually believe that I could have — "

He turned away. His voice was unsteady, and he looked very ill; he was evidently suffering under a confusion of violent and perplexing emotions, and Mary could only pity him.

"Come, Henry," she said softly. "Your spirits are exhausted, and I doubt you have either eaten or slept properly for days. Let me call for a basin of soup, and we will talk about this again tomorrow."

"No," said Henry, with unexpected decision. "If this Maddox wishes to see me, I will not stay to be sent for. I have nothing to hide."

Dr Grant eyed him, shaking his head in steady scepticism. "I hope so, for your sake, Crawford."

The two ladies turned to look at him, as he continued. "We here at Mansfield have spent the last week conjecturing and speculating about the death of Miss Price, but it seems that we were all mistaken. It was not Miss Price at all, but Mrs Crawford. That puts quite a different complexion on the affair, does it not?"

Mary’s eyes widened in sudden fear. "You mean — "

"Indeed I do. Whoever might have perpetrated this foul crime, it has made your brother an extremely rich man. As Mr Maddox will no doubt be fully aware."

At that very moment, Charles Maddox was sitting by the fire in Sir Thomas’s room. It was a noble fire over which to sit and think, and he had decided to afford himself the indulgence of an hour’s mature deliberation, before going in to dinner. He had not yet been invited to dine with the family, but such little indignities were not uncommon in his profession, and he had, besides, gathered more from a few days in the servants’ hall than he could have done in the dining-parlour in the course of an entire month. They ate well, the Mansfield servants, he could not deny that; and Maddox was a man who appreciated good food as much as he appreciated Sir Thomas’s fine port and excellent claret, a glass of which sat even now at his elbow. He got up to poke the fire, then settled himself back in his chair.

Fraser had completed his questioning of the estate workmen, and although he had assured his master that there was nothing of significance to report, Maddox was a thorough man, and wished to read the notes for himself. There were also some pages of annotations from Fraser’s interviews with the Mansfield servants. Maddox did not anticipate much of use there, either; he had always regarded both maids and men principally as so many sources of useful intelligence, rather than probable suspects in good earnest. Moreover, only the female servants had suffered that degree of intimacy with Miss Price that might have led to a credible motive for her murder, and he could not see this deed as the work of a woman’s hand. Stornaway, by contrast, had spent the day away from the Park, interrogating innkeepers and landlords, in an effort to determine if any strangers of note had been seen in the neighbourhood at the time of Miss Price’s return. Now that Maddox knew she had indeed eloped, it was of the utmost necessity to discover the identity of her abductor. If Stornaway met with no success, Maddox was ready to send him to London; it would be no easy task to trace the fugitives, and Maddox was mindful that the family had already tried all in its power to do so, but unlike the Bertrams, he had connections that extended from the highest to the lowest of London society; he knew where such marriages usually took place, and the clergymen who could be persuaded to perform them, and if a special licence had been required, there was more than one proctor at Doctors-Commons who stood in Maddox’s debt, and might be induced to supply the information he required.

It was little more than ten minutes later when the silence of the great house was broken by the sound of a commotion in the entrance hall. It was not difficult to distinguish Mrs Norris’s vociferous tones in the general fracas, and knowing that lady was not in the habit of receiving visitors any where other than in the full pomp and magnificence of the Mansfield Park drawing-room, he suspected something untoward, and ventured out to investigate the matter for himself. The gentleman at the door was a stranger to him, but first impressions were Maddox’s stock-in-trade. He prided himself on his ability to have a man’s measure in a minute, and he was rarely wrong.This man was, he saw, both weary and travel-soiled, but richly and elegantly attired. Maddox was something of a connoisseur in dress; it was a partiality of his, but it had also proved, on occasion, to be of signal use in the more obscure by-roads of his profession. He could, for example, hazard a reasonable estimation as to where these clothes had been made, by which London tailor, and at what cost. This was, indeed, a man of considerable air and address; moreover, the set of his chin, and the boldness of his eye, argued for no small measure of pride and defiance. Yet, in spite of all this, it piqued Maddox’s curiosity not a little to see that Mrs Norris accorded the newcomer neither courtesy nor common civility, and her chief object in leaving the sanctuary of the drawing-room for the draughtiness of the hall seemed to be to compel the footmen to expel the intruder without delay.

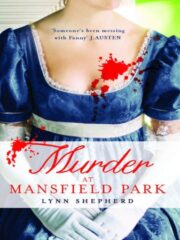

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.