She hesitated, then acquiesced, her hands twisting the handkerchief in her lap all the while.

"Good. So I will ask you once more, what is it that you fear your sister will divulge?"

A pause, then, "She heard me tell Fanny that I wished she were dead."

"I see. And when was this?"

"At Compton. The day we visited the grounds."

Maddox nodded, more to himself than to his companion, whose eyes were still fixed firmly on the ground; one piece of the puzzle had found its correct place.

"I was — angry — with Fanny," she continued, "and I spoke the words in haste." Her voice dropped to barely a whisper. "I did not mean it."

Maddox smiled. "I am sure we all say such things on occasion, Miss Bertram, and from what I hear, your cousin was not, perhaps, the easiest person to live with, even in a house the size of this. Why should such idle, if unfortunate words have caused you so much anxiety?"

It was his normal practice to ask only those questions to which he had already ascertained the answer, and this was no exception; but even the most proficient physiognomist would have been hard put to it to decide whether the terror perceptible in the young woman’s face was proof of an unsophisticated innocence — or the blackest of guilt.

Maria put her handkerchief to her eyes. "After Fanny and I quarrelled in the wilderness I ran away — but — but — my eyes were full of tears and I could hardly see. I stumbled on the steps leading up to the lawn, and made my nose bleed. I did what I could to staunch it, but the front of my dress was covered with blood. I was mortified to be seen so in public, so I concealed the stain with my shawl, that no-one should perceive it. As a result I alone know how and when the blood came to be there."

"You did not ask your maid to launder the gown?"

She shook her head. "Not at first. I had not spirits to bear even her expressive looks. Insolence would have been intolerable, but pity infinitely worse. And when Fanny’s body was found, it was too late. I became more and more terrified. It was as if some frightful trap had been laid for me. I thought that if — "

" — if I searched your room I would discover this dress, and draw the obvious — indeed the natural — conclusion. I confess I did wonder why you were so adamant in your refusal to permit such a search."

"How could I have proved that the blood was my own? Such a thing is impossible."

"Quite so," said Maddox, who reflected to himself in passing that, unlike any other injury, a nose-bleed offered the invaluable advantage of leaving no visible scar or sign thereafter, which made Maria Bertram either transparently guiltless, or quite exceptionally devious. He had his own ideas on that subject, but he had not finished with her yet. "I can quite understand why you should have been concerned, Miss Bertram. And, if I may say so, your explanation seems most convincing."

Her head lifted, and she looked at him in the face for the first time. "O, how you do relieve me!" she burst out. "I have not slept properly for days — not since — "

Maddox held up his hand. "There is just one more thing, Miss Bertram. One last question, if I may. If you are indeed as innocent as you claim, why did you induce your maid to lie?"

Her eyes widened in terror, and he saw her lips form into a no, though the sound was inarticulate.

"There is nothing to be gained by denying it, Miss Bertram — I have spoken to the young woman myself. Do not blame her, I entreat. Your Kitty is one of the most loyal creatures I have ever encountered in her station in life, although I own the ten shillings you gave her would have been a most efficacious reinforcement of her natural tendencies. It was an admirable amount to fix upon, if I may say so — not too large, not too small. Bribery is always such a tricky thing to carry off, especially for a novice: pay too much, and you put yourself in the power of a servant, offer too little, and a greater price — or a greater threat — may be your undoing. And, I am afraid, it proved to be so in this case. Kitty Jeffries was proof against my pecuniary inducements, but even she could not withstand George Fraser. He has never failed me yet."

He paused; he was not proud of what he had done, but the wench had suffered no real harm, and he had got the truth from her. Maria Bertram was, by now, sobbing as bitterly as her maid had done not twelve hours before.

"I see that you are unwilling — or unable — to speak. I, then, will speak for both of us. I have a little theory of my own, Miss Bertram, and with your permission, I will indulge myself by expatiating on it for a moment. I believe that you did, indeed, leave your room that morning, and your maid saw you go. I believe you were still angry with your cousin, and this anger had festered for many months, nay, possibly even years. Matters drew to a crisis over Mr Rushworth, and contrary to what one might have expected, your cousin’s disappearance, and the news of Mr Rushworth’s engagement, did nothing to assuage your fury and resentment. Rationally or not, you blamed his defection on Miss Price, and in your eyes, this was only the last of a long series of incidents in which you had been demeaned and humiliated, thanks to her. I believe you were in this same bitter and revengeful state of mind that morning, when, to your enormous astonishment, you saw Miss Price walking towards you near the channel being dug for the new cascade. What you said to one another, I cannot at present divine, but whatever it was, it ended with you striking your cousin a blow across the face. The rest, I admit, is conjecture on my part, but I surmise that whether from pain or shock, Miss Price fell to her knees before you, under the force of this blow, leaving you ashamed, appalled, and perhaps a little exhilarated, at the enormity of what you had done. Doing your best to contain these tumultuous feelings, you returned to the house at once, without daring to look back. Having regained your room, you remained there in a state of the utmost fear and expectation, dreading every moment to hear a commotion in the hall, as Miss Price arrived to accuse you, but time dragged on, and nothing of the kind occurred. By nightfall you were forced to conclude that she must have returned from wherever it was she had come. But the following day her body was discovered, and you were compelled to face the unspeakable possibility that the blow you had struck was far worse than you had perceived, or meant. You had, in fact, committed murder."

He had never yet used that word, and it had the predictable effect on the already high-wrought nerves of his companion. He sat back in his seat and took out his snuffbox. "Now, Miss Bertram. Perhaps you can tell me whether my theory requires some emendation?"

She took a deep breath. "Very little, Mr Maddox," she whispered. "You are correct in almost every particular. Except one."

"And that is?"

"I did look back. I could hardly bring myself to do it, but something — some impulse — made me turn around. She was still there — lying on the ground where I had left her, screaming at me. I cannot get the sound out of my head. It haunts me, both sleeping and waking."

Maddox could well believe it; her spirits were clearly quite exhausted. "So when they found the body, you presumed that she must have fallen into the trench, and been unable to save herself, dying a lingering and terrible death, from the effects of hunger, no more than a few short hours thereafter."

Maria put her head in her hands, and her slender frame was racked with sobs.

Maddox took a pinch of snuff. "This is not the first time I have had cause to remark on the deficiencies of young ladies’ education, particularly in relation to what we might term the human sciences. A well-nourished young woman like Miss Price could not possibly have succumbed to starvation in so short a period, and certainly not if she retained the use of her lungs, and the ability to call for help. Now tell me, Miss Bertram, did you see the body when they brought it home?"

She shook her head, and murmured something in which the words "my cousin Edmund" were distinguishable.

Maddox nodded; it was of a piece with everything he knew of the public character of Edmund Norris to have stipulated that the young ladies should be protected from such a shocking and distressing spectacle, but on this occasion his interference had had terrible and unintended consequences.

"Your cousin’s consideration for you has, for once, done you a grave disservice. Had you been permitted to see it with your own eyes, rather than relying for your information on rumour and servants’ gossip, you would have saved yourself many hours of needless grief and self-reproach.The wounds inflicted on Miss Price were far more grievous than anything you describe. The blows that killed her were made by an iron mattock, not a human hand."

Maria raised her head and stared at him, daring, for the first time in days, to allow herself the possibility of hope. "But how do you know that I am telling the truth — that I did not pick that mattock up and wield it, just as you say?"

Maddox shook his head, and smiled. "You have the proof, there, in your own hand."

Her expression of uncomprehending amazement was, he had to admit, exceedingly gratifying, and one of the subtler pleasures of his chosen profession.

"I do not take your meaning. I have nothing in my hands — nothing of relevance."

"On the contrary. Before I intruded upon you, you were engaged in needlework, were you not?"

"Yes, but — "

" — and, if I am not mistaken, you hold your needle in your left hand? And your pen, when you write?"

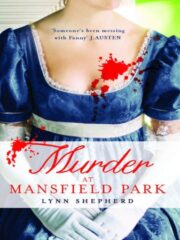

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.