"I was not aware it was so long," he stammered.

Maddox linked his hands behind his back. "You are an educated man, Mr Norris, and as such you will be aware that, given these facts, it would have been quite possible for you to have seen Miss Price — and not only seen her, but met with her, and talked to her. Indeed, it almost defies belief that such an encounter did not take place. And it would hardly have been a congenial reunion. You would, indeed, have had good cause for resentment on Miss Price’s account. To be subjected to the shame of a public jilting — what man of any character could submit to that with equanimity? And there is, of course, the small matter of her very considerable fortune."

"You need not concern yourself about that," said Mrs Norris quickly, her face red. "My son has plenty of money of his own."

"In my experience, madam," said Maddox coolly, "all men covet money, however lofty their professed indifference; many are willing to die for it, and some are prepared to kill for it. So, Mr Norris, I repeat: what, precisely, happened in the park that morning?"

Mary felt quite sick with fear and apprehension; she could not dispute Maddox’s reasoning, but her heart shrank from what that reasoning implied. She did not — could not — believe Edmund guilty of such an act of horror and violence, however cruelly provoked, but she could not deny that his actions had driven him into the appearance of such guilt. She could quite believe that Maddox found his story incredible; she alone, of all the family, might have been able to account for such uncharacteristic perturbation of mind, but how could she, with propriety or delicacy, supply Maddox with the explanation he lacked? And even if she overlooked her own scruples, was it not equally possible that Maddox might consider that if Edmund was in love with her, and not Fanny, that would only serve to provide him with an even more cogent motive for committing the very act from which she hoped to exonerate him? She could barely keep still, terrified of what Maddox might say next. Would he have Edmund apprehended there and then? Were his odious assistants even now summoning magistrates and constables from Northampton? It was altogether horrible, and in her anxiety for Edmund, it did not occur to her to fear for herself: not until much later did she perceive that what Maddox had said of Edmund, he could equally well have said of her.

Edmund, meanwhile, appeared to have regained his composure. He looked first at his family, and then at Maddox."You have my word, sir, as a gentleman, that no such encounter with Miss Price took place, either then, or at any other time. I can offer no corroborating circumstances or exculpatory evidence; my word alone will have to suffice."

His voice was both cool and steady, and the two men remained stationed thus for what seemed to Mary to be an age, gazing upon one another in silence. Then Maddox suddenly gave a brief bow. "Thank you," he said, "I have all I need. For the present."

Having uttered these words, he walked so swiftly to the door as to forestall the footmen, and were the notion not so ludicrous, Mary might have been tempted to think he did so to ensure that no-one inside the room should perceive that there had been someone listening outside. There was certainly nobody in evidence when Mary followed Maria Bertram through the door and into the hall; Edmund had departed without another word, and as she was endeavouring to determine where he might have gone, her thoughts were distracted by the sight of Mr Gilbert descending the stairs.

Maddox stood in the door of the drawing-room, and observed as the family went their several ways. It had been a most rewarding morning, and it was not done with yet. He had read widely on the subject of physiognomy, and to this theoretical knowledge of facial features, the pursuance of his profession had added a practical proficiency in the interpretation of gesture and demeanour. He regularly derived considerable amusement from scrutinising people at a distance, and deducing the state of relations between them, and many times, as now, this faculty had proved to be of the greatest service in the course of his work. He, too, had noted the appearance of the physician, and he now watched his meeting with Miss Bertram and Miss Crawford with the keenest interest. It was evident that Gilbert had promising tidings to impart, and the satisfaction writ across his face was quickly communicated to one, at least, of his companions: Miss Crawford’s relief was immediate and unfeigned; Miss Bertram’s response to the news, however, was rather more finely chequered. She seemed to be very much aware that she ought to look happy, without really being so; it was the impression of a moment only, but Maddox thought he discerned something that looked, to his trained eye, very much like fear. "Now why," he thought to himself, "should that be so?"

As Mr Gilbert turned to spread his happy news to the rest of the family, the two young women went out onto the sweep; Miss Crawford began to walk down the drive towards the parsonage, while Miss Bertram appeared to be making her way to the garden. Maddox followed them out of the house and lingered a moment, watching the retreating figure of Mary Crawford, and suppressing the urge to follow her; something told him that this young woman had a role to play yet, in this affair.What that might be, he could not tell, but he owned himself engrossed to an unprecedented and possibly dangerous degree with the captivating Miss Crawford. For a moment the man strove with the professional, but the professional prevailed. He turned away, and walked briskly in the direction of the garden.

Maria had taken a seat in the alcove at the farther end from the gate, and although she had drawn a piece of needlework from her pocket, she let it fall in her lap when she saw Maddox approaching. Her position afforded each the opportunity of observing the other as he drew near. He looked all confidence, but Maria’s feelings were not as easily discerned as they had been in the hall; she knew herself to be under scrutiny, and was more guarded as a consequence.

"May I?" said Maddox.

"It appears you have little regard for the niceties of common civility, Mr Maddox," she replied archly. "I dare say you will sit down whether I give my permission or no."

"Ah," he said with a smile, as he sat down beside her, "there you are wrong, Miss Bertram, if you will forgive me. There are few men who are more watchful of what you term “niceties” than I am. Many of my former cases have turned on such things. In my profession it is not only the devil you may find in the detail."

Maria replied only with a toss of her head; she seemed anxious to be gone, but unable to take her leave without appearing ill-mannered. Maddox smiled to himself — these fine ladies and gentlemen! It was not the first time that he had seen one of their class imprisoned by the iron constraints of politeness and decorum.

"To tell you the truth, I followed you here, precisely so that we might have this chance to talk privately," he continued. "I wished to elucidate one or two points, but felt that you would prefer to discuss these matters when the rest of your family were not present."

He received a side-glance at this, but nothing more.

"You stated, just now, that you remained in your own room for the whole morning on Tuesday last, and that your maid was with you. You still hold to that? There is nothing you wish to add — or, perhaps, modify?"

"No," she said, her colour rising. "I have told you everything you need to know."

"I fear," he said, with a shake of the head, "that that is not the case. But let us leave the matter there for the moment. Why are you so concerned that your sister may soon be in a position to speak to me?"

A slight change in his tone ought to have been warning enough, but she had not heeded it.

"I–I — do not know what you mean," she stammered, her face like scarlet.

"It is not wise to trifle with me, Miss Bertram, and even more foolish to attempt to deceive me. I saw it with my own eyes only a few minutes ago. Mr Gilbert told you that Miss Julia may soon be recovered enough to speak, did he not? I saw the effect this intelligence had upon you — and how intent you were to disguise it."

"How could you possibly — "

Maddox smiled. "Logic and observation, Miss Bertram, logic and observation. They are, you might say, the tools of my trade. Mr Gilbert had good news, that much was obvious; ergo, your sister is recovering. And if your sister is recovering, she will soon be able to speak. This intelligence clearly disturbs you; ergo, you must fear what it is she is likely to say. Simple, is it not?"

She was, by now, breathless with agitation, and had her handkerchief before her face."I am not well," she said weakly, attempting to rise, "I must return to the house."

"All in good time," said Maddox. "Let us first conclude our discussion. You may, perhaps, find that it is not quite as alarming as you fear at this moment. But I have taken the precaution of providing myself with salts. I have had need of them on many other like occasions."

Maria took them into her own hands, and smelling them, raised her head a little.

"You are a villain, sir — not to allow a lady on the point of fainting — "

"Not such a villain as you may at present believe. But no matter; I will leave it to your own conscience to dictate whether you do me an injustice on that score. But to the point at hand. I will ask you the question once again, and this time, I hope you will answer me honestly. I can assure you, for your own sake, that this would be by far the most advisable way of proceeding."

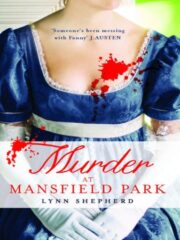

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.