"May I begin by thanking you for your prompt compliance with my request for an audience this morning," Maddox began, in a manner that was perfectly easy and unembarrassed."As I have been explaining to Miss Crawford, I have just now received certain most interesting information. We have, at last, a witness." He stopped a moment, as if to ensure that his announcement would produce the greatest possible effect.

"Miss Price was seen by a local man, at the back gate to Mansfield, three mornings ago, some time between eight and nine o’clock. Since she never reached the Park, I believe we may safely presume that she met her death at, or around, that time."

There was a general consternation at this: Edmund turned abruptly round, his face drawn in shock and dismay; Maria gasped; and Lady Bertram drew out her handkerchief and began to cry quietly. Mary was, perhaps, the only one with sufficient presence of mind to observe Maddox at this moment, and she saw at once that he was equally intent on observing them. "So he has contrived this quite deliberately," she thought; "he plays upon our feelings in this unpardonable fashion, merely in order to scrutinise our behaviour, and assess our guilt." But angry as she was, she had to own a reluctant admiration for his method, even if it owed more to guile and cunning, than it did to the accustomary operations of justice. There doubtless were inveterate criminals so hardened to guilt and infamy as to retain control over their countenances at such a moment, but the members of the Bertram family could not be numbered among them. Maddox had succeeded in manoeuvring them all into displaying their most private sentiments in the most public fashion.

"My purpose, then," he continued, his calm and composed manner providing the most forcible contrast with the state of perturbation all around him, "is to ask you all, in turn, where you were that morning. It will be of the utmost usefulness to my enquiries. So, shall we begin?"

This was all too much for Mrs Norris, who had sat swelling for some minutes past, and now shewed two spots of livid colour on her cheeks. "This is the most extraordinary impertinence! Question us, indeed! And in such a barbarously uncouth manner! When it is as plain as it could possibly be that it must have been one or other of those blackguardly workmen — why we do not cart the lot of them off to the assizes at once I still cannot conceive. A night or two without bread or water and we would soon have our confession — I never did like the look of that tall one with the eye patch — "

But here she was interrupted. "My dear aunt," said Tom, "I am sure we all wish to see this dreadful matter cleared up as soon as possible, do we not? If it will assist Mr Maddox, what objection can we have? It is, after all, quite impossible that any of us were responsible."

Mary wondered whether Tom’s readiness to accede to Maddox’s request owed more to his knowledge of his own complete innocence in the affair, or to a recognition that he had brought this man into the house, and would be the one answerable if the enterprise should fail.

"I shall set the example, Mr Maddox," he said. "You may begin with me. I was in my room until ten o’clock, and after a late breakfast I spent an hour with my father’s bailiff, Mr Fletcher. He will be able to confirm that."

Maddox nodded. "And her ladyship?"

Lady Bertram looked up; her eyes were heavy, and she seemed not to have heard the question. "I am sorry, were you speaking to me?" she said, in the languid voice of one half-roused.

Tom turned towards his mother. "Mr Maddox wishes to know how you occupied your time on Tuesday last, ma’am. Most particularly the time before breakfast."

Lady Bertram seemed bewildered that anyone should even ask such a thing. "I was in my room, where else would I be? Chapman came to dress me as usual, and I had a dish of chocolate. I do not understand — what can this have to do with poor dear Fanny?"

Her tone was becoming agitated, and Tom endeavoured to soothe her, saying at once, "Oh no, ma’am — I am sure nobody suspected you!"

"Quite so," said Maddox, with the most deferential of bows. "I seek merely to obtain the fullest possible picture of where everyone in the house was at that particular time. There is no cause to distress yourself, your ladyship."

"I am very happy to tell you where I was, Mr Maddox," said Mary, in an effort to draw attention away from Lady Bertram. "I spent the morning in the garden with my sister, cutting roses."

"Indeed," said Maddox in a steady tone. "And before that, Miss Crawford?"

Mary flushed; she had quite forgotten her fruitless excursion to the post-office, and the conviction was of a sudden forced upon her that Maddox was already fully apprised of every aspect of her movements that day. "Well, I did walk to the village that morning — "

"So I have been informed. I am delighted that you have elected to be so thorough in your disclosure. Did you see anyone during this no doubt pleasant little walk? Aside from the post-boy, of course?"

Mary shook her head. "No, I did not."

The expression on Maddox’s face was unfathomable. "That is a pity. Let us hope it does not prove to be significant."

Mary opened her mouth to reply, but Maddox had already turned his attention to Maria. "Perhaps Miss Bertram might now be so good?"

Maria might look a good deal thinner and paler than she had used to do, but she appeared to have assumed once more all the hauteur owing to a Miss Bertram; it was with the pride and dignity of a daughter of a baronet that she met the thief-taker’s gaze. "I was somewhat indisposed, as I recall. I remained in my room all morning, with my maid in attendance."

"You did not speak to anyone during all that time? Aside from your maid, of course."

Maria shook her head. "No. I saw no-one."

Maddox gave a broad smile, and linked his hands behind his back. "Your clarity is admirable, Miss Bertram. And you, ma’am?" he said, turning to Mrs Norris. "Perhaps you also took a walk in the park? I gather Miss Crawford was not alone in seeking air and exercise that morning — I am told Miss Julia was also some where in the vicinity."

"Well, I most certainly was not. I have better things to do than wandering about on wet grass catching my death of cold. I was in my store-room, sir, as any respectable matron would be at that time of the morning. And you need not trouble to question my son, neither. He did not return from Cumberland until just before luncheon, and he left for the parsonage almost immediately, when we heard what had happened to Julia."

Maddox was not the only one in the room to turn towards Edmund at this; he was still standing in the window, but Mary saw at once that his demeanour was not as collected as it had been.

"Is this true, Mr Norris?" asked Maddox genially. "The briefest of discussions with the stable-hands, would, of course, resolve all doubt."

"For heaven’s sake, tell him, Edmund," said Mrs Norris impatiently. "Let us have done with this, once and forever."

Edmund gave a slight cough. "Mr Maddox will have no need to trouble the grooms. As it happens, I arrived in Mansfield somewhat earlier than my mother might have supposed. The difference is easily accounted for: I was glad to be released, after such a journey, from the confinement of a carriage, and ready to enjoy all the luxury of a walk in the fresh air, to collect my thoughts."

Maddox gave a disarming smile. "It seems that the park was more than usually crowded on Tuesday last. You had, I conclude, much on your mind?"

Edmund appeared to hesitate, before regaining his confidence. "Evidently. But my private cogitations are my own affair, and can have no conceivable bearing on your enquiries, Mr Maddox."

Maddox was unperturbed. "I will determine what does, and does not, have a bearing on my enquiries, Mr Norris. So how long did you devote to this perambulation? Let me be absolutely clear: at what time, precisely, did you return to Mansfield that day?"

Edmund flushed. "I am not entirely sure. Perhaps eleven o’clock."

Maddox took a memorandum book from his pocket, and opened it with a theatrical flourish. "According to the information supplied to my assistant yesterday by the stable-boy, you arrived just before nine o’clock. He is quite sure of this, because the great clock at Mansfield happened to chime as he was unharnessing the horses. I say again, it was not eleven o’clock, as you claim, but nine. Having employed one of Sir Thomas’s carriages for the journey, you naturally came directly to the stables here, but then, rather than going into the house, you told your valet that you would, instead, walk across the park to the White House. Rather an irregular way of proceeding, would you not say?"

"What do you mean to imply by that?"

Maddox snapped his pocket-book shut. "I imply nothing; I enquire merely. However, I am sure I would not be alone in regarding it as rather curious for a gentleman in your position, returning to a house in turmoil, and a family in dire need of him, to dawdle among the delphiniums for upwards of three hours."

Edmund’s colour was, by this time, as heightened as Mary had ever seen it, and it had not escaped her notice that, whether he knew it or not, he had reverted to the stiff and officious mode of discourse that had characterised his manner on their first acquaintance, and which her brother had once found so entertaining. There was no possibility of entertainment now; knowing him as she did, Mary feared, rather, that the alteration in his elocution betrayed a mind profoundly ill at ease.

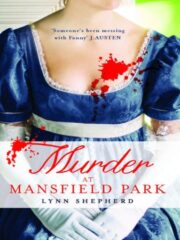

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.