"No! No!" she screamed. "Tell me she is not dead! She cannot, cannot be dead!"

"Oh my Lord!" cried Mrs Baddeley, rushing to Julia’s aid. "This is just what I tried to prevent!"

Mary turned at once to the footmen, who were standing motionless, half stupefied. "Go at once," she said quickly. "Make haste with the coffin, if you please. Miss Julia should never have seen this."

"Did I not tell you, not an hour since,"said the housekeeper, casting a furious look at the maid who had just appeared at Julia’s side, "that on no account was Miss Julia to be allowed to leave her bed this afternoon? Heavens above, girl, what were you thinking of?"

The maid was, by this time, almost as horror-struck as her young mistress, and stammered between her tears that "They would have stopped her had they only known, but Miss Julia had insisted on rising — she said she wished to see her brother, and she seemed so much better, that they all thought some fresh air would do her good."

"As to that, Polly Evans, it’s not for you to think thoughts, it’s for you to do as you’re told. Heaven only knows what Mr Gilbert will say. It will be a miracle if serious mischief has not been done."

This did little to calm the terrified maid, who looked ready to fall into hysterics herself, and Mary motioned to Mrs Baddeley to take the girl to her own quarters, while she helped Julia back to her bed. She was by this time in a state of such extreme distress that Mary sent one of the servants to fetch Mr Bertram, with a request that the physician be summoned at once. But as she waited anxiously for his arrival, it was not Tom Bertram, but Edmund, who appeared at the door. When he saw his young cousin lying insensible on the bed, moaning and crying indistinctly, his face assumed an expression of the most profound concern.

"Is there anything I can do to assist?"

Mary shook her head. "I have administered a cordial, but I fear something stronger is required."

Edmund nodded. "I concur with your judgment. Let us hope Gilbert is not long in arriving." As he spoke the words his eyes stole to her face, and he saw for the first time that Mary, too, was wan and tremulous. A glance at the apron, with its tell-tale stains, lying disregarded on the chair, told him all that was needful for him to know.

"So it was you! You were the one who — " He stopped, in momentary bewilderment. "When I saw the coffin being carried through the hall I thought — at least, I had no conception that it was your kindness — "

Mary had borne a good deal that day, but it was the gentleness of his words, rather than the horror of what she had seen and endured, that proved her undoing. She turned away in confusion, hot tears running down her face. Edmund helped her to a chair, and rang the bell.

"You are overcome, Miss Crawford, and I can quite comprehend why. You have over-taxed yourself for our sakes, and I am deeply, everlastingly, grateful. But I am here now, and I can watch with my cousin until Mr Gilbert arrives. You look to stand in great need of rest and wholesome food. I will ring for it directly."

Being obliged to speak, Mary could not forbear from saying something in which the words "Mrs Baddeley’s room" were only just audible.

"I understand," said Edmund, with a grim look, and not wanting to hear more. "I understand. I have allowed this unpardonable incivility to continue for far too long. I will arrange for you to take a proper meal in the dining-parlour, as befits a lady, and one to whom we all owe such an inexpressible obligation."

Such a speech was hardly calculated to compose Mary’s spirits, but he would brook no denial, and within a few minutes she was settled in a chair by the fire downstairs, being helped to an elegant collation of minced chicken and apple-tart. Both her head and her heart were soon the better for such well-timed kindness, and when the maid returned with a glass of Madeira with Mr Norris’s compliments, Mary enquired at once whether Mr Gilbert had yet been in attendance.

"I believe so, miss. Mrs Baddeley said he’d given Miss Julia something to help her sleep."

Mary nodded; such a measure seemed both prudent and expedient; they must all trust to the certainty and efficacy of some hours’ repose. She thanked the maid, and sat for a few minutes deliberating whether it would be best to return to the parsonage; her sister must be wondering where she was. She was still debating the matter when she heard the sound of a carriage on the drive, and went to the window. It was a very handsome equipage, but the horses were post, and neither the carriage, nor the coachman who drove it, were familiar to her. The man who emerged was a little above medium height, with rather strong features and a visible scar above one eye. His clothes, however, were fashionable and of very superior quality, and he stood for a moment looking confidently about him, as if he was weighing what he saw, and putting the intelligence aside for future use. He was not handsome — or not, at least, in any conventional manner — but there was something about him, a sense of latent energy, of formidable powers held in check, such as might command attention, and draw every eye, even in the most crowded of rooms. As she observed him ascend the steps to the door, Mary did not need to overhear the servant’s announcement to guess that the man before her was none other than Mr Charles Maddox.

A few moments later, this impressive and uncommon personage was being shewn into Sir Thomas’s room, where Mr Bertram and Mr Norris were awaiting him. The former had taken up the post of honour behind his father’s desk, while his cousin was standing by the window, evidently ill at ease. They had both been to Oxford, and no doubt considered themselves men of the world, but such a creature as Maddox was far beyond their experience.

"Good day to you, sirs!" said their visitor, with the most perfunctory of bows. "I admire your discernment. This will do admirably."

"I am not sure I understand you," said Tom, who had not expected such extraordinary self-assurance from a man who was to be in his employ.

But Maddox had already assumed a proprietorial air, and was wandering about the room, running his hand over the furniture, and inspecting the view from the windows. "This will make a very suitable “seat of operations”, as I like to call it. I will have my assistants set up in here."

"But this is my father’s room — " began Tom, looking at him in consternation.

Maddox waved his hand. "You have nothing to fear on that score, Mr Bertram. His house shall not be hurt. For everything of that nature, I will be answerable. And my men are good men. They know how to behave themselves, even in such a grand house as this one."

Tom and Edmund exchanged a look in which there was as much anxiety on the one side, as there was reproof on the other; the door then opened for a second time, and two men appeared, carrying a large trunk. One was tall and thin, with a pock-marked face; the other short and stout, with a reddened and weather-beaten complexion, and his fore-teeth gone. They set down their burden heavily on the carpet, then departed as they had come, without a word, but leaving behind them a distinct waft of tobacco. Maddox, meanwhile, had installed himself comfortably in an elbow-chair, without staying to be asked.

"And now to business," he said, genially. "You agree to my terms, both as to the daily rate, and the reward in the event of an arrest?"

Tom endeavoured to regain the dignified manner suitable to the head of such a house, and to reclaim the mastery of the situation. "We consider ourselves fortunate to be able to call upon a man of your reputation, Mr Maddox. Indeed, we are relying on you to bring matters to a prompt and satisfactory conclusion."

"My own aim, entirely," said Maddox, with a smile."And in the pursuit of same, may I begin by examining the corpse?"

The two gentlemen absolutely started, and for a moment both seemed immoveable from surprise; but Edmund shortly recovered himself, and said in a hoarse voice, "You cannot possibly be in earnest, Mr Maddox. It is quite out of the question."

Mr Maddox frowned. "I assure you I am in the most deadly earnest, Mr Norris. The precise state of the body — the nature of the injuries, the advancement of putrefaction, and such like matters — are all of the utmost significance to my enquiries. It is the evidence, sir, the evidence, and without it, my investigation is thwarted before it even commences."

"You mistake me, Mr Maddox," said Edmund coldly, a deep shade of crimson overspreading his features. "It is out of the question, because the coffin has already been sealed. To open it again — to break open the shroud — would be a sacrilegious outrage that I cannot — will not — permit."

"I see," said Maddox, eyeing him coolly. "In that case, may I be permitted to speak to the person who laid out the corpse? It is a poor substitute, but in such a circumstance, secondhand intelligence is better than no intelligence at all."

Tom hesitated, and looked to his cousin. "What think you, Edmund? May we impose so much on Miss Crawford’s kindness?"

"Could such an importunate interview not wait a few days?" said Edmund, angrily. "It has been a distressing day for us all, and for none more so than Miss Crawford. She finished laying out the body not two hours ago."

"So much the better," replied Maddox. "The lady’s memory will be all the fresher for it. You would be surprised, Mr Norris, how quickly one’s powers of recall weaken and become confused, especially in cases such as this, when the mind is exerting itself to throw a mist over unpleasantness. We all believe our faculties of recollection to be so retentive, yet I have questioned witnesses who would swear to have seen things that I know, from my own knowledge, to be absolutely impossible. And yet they sincerely believe what they say. Which is why it is essential that I speak with this Miss Crawford without delay. There is not a moment to lose."

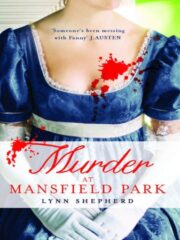

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.