"If you please, Rogers," said Mary, her voice thick, "tell me what has happened — I have only the dimmest recollection as to how I came to be here."

Rogers sat down heavily in the chair, her face grim. "Are you sure, miss? Mr Norris said you weren’t to be upset. Most insistent, he was."

"I am sincerely grateful to Mr Norris for his consideration," she said, treasuring the thought, "but you need not worry. I was, I admit, overcome by a fit of nervous faintness, but I do not usually suffer from such things, and I am quite recovered now. I would much rather know exactly what has occurred."

"If you say so, miss," said Rogers, who clearly still had her doubts on the matter. "It was Mr McGregor who brought you back. You was leaning on his arm and you looked so queer! Of course, none of us knowed why then, and Mr McGregor barely had time to tell Mr Baddeley what it were all about before he was off again on horseback to fetch the constable, though what use they think old Mr Holmes is going to be is beyond me. He must be sixty if he’s a day. Anyway, that’s when we knowed it were serious, but we didn’t find out what was really going on until the footmen came back. They’d covered it over as much as they could, but there was this one hand hanging down, all spattered in mud, and jolting with every move of the cart. Gave me quite a turn, I can tell you. Young Sally Puxley fainted clean away."

Mary turned her face against the pillow, and closed her eyes. So it had not been a dream; it had seemed so shocking, that her heart revolted from it as impossible, but she knew now that the sickening images that had floated before her in her stupor were not, after all, some hideous concoction of memory and imagination, but only too horribly real.

"Are you all right, miss?" said Rogers quickly. "You’ve come over dreadful pale again."

"So it’s true," Mary whispered, half to herself. "Fanny Price is dead."

Chapter 12

When Mary opened her eyes again, the morning sun was streaming through the window. For a few precious moments she enjoyed the bliss of ignorance, but such serenity could not last, and the events of the previous day were not long in returning to her remembrance. She felt weak and faint in body, but her mind had regained some part of its usual self-possession, and she dressed herself quickly, and went out into the passage. She was in a part of the house she did not know, and she stood for a moment, wondering how best to proceed. It then occurred to her that she might take the opportunity to locate Julia Bertram’s chamber, and try if she might be permitted to see her. To judge from Rogers’s words the preceding day, Julia might even have recovered sufficiently to rise from her bed. Mary made her way down the corridor, hearing the sounds of the mansion all around her; the tapping of servants’ footsteps and the murmur of voices were all magnified in a quite different way from what she was accustomed to, in the small rooms and confined spaces of the parsonage. A few minutes later she saw a woman emerging from a door some yards ahead of her, carrying a tray; it was Chapman, Lady Bertram’s maid. The woman hastened away without seeing her, and Mary moved forwards hesitatingly, not wishing to appear to intrude. As she drew level with the door she noticed that it was still ajar, and her eyes were drawn, almost against her will, to what was visible in the room.

It was immediately apparent that this was not Lady Bertram’s chamber, but her daughter’s; Maria Bertram was still in bed, and her mother was sitting beside her in her dressing gown. Mary had not seen either lady for more than a week, and the change in both was awful to witness. Lady Bertram seemed to have aged ten years in as many days; her face was grey, and the hair escaping from under her cap shewed streaks of white. Maria’s transformation was not so much in her looks as in her manner; the young woman who had been so arch and knowing when Mary last conversed with her, was lying prostrate on the bed, her handkerchief over her face, and her body racked with muted sobs. Lady Bertram was stroking her daughter’s hair, but she seemed not to know what else to do, and the two of them formed a complete picture of silent woe. Mary had no difficulty in comprehending Lady Bertram’s anguish — she had supplied a mother’s place to Fanny Price for many years, and the grief of her death had now been superadded to the public scandal of her disappearance; Maria’s condition was more perplexing. Some remorse and regret she might be supposed to feel at Fanny’s sudden and unexpected demise, but this utter prostration seemed excessive, and out of all proportion, considering their recent enmity.

Mary was still pondering such thoughts when she became aware of a third person in the room: Mrs Norris was standing at the foot of the bed, observing the two women almost as intently as Mary herself. A slight movement alerting that lady to Mary’s presence, she moved at once towards the door with all her wonted vigour and briskness.

"I do not know why it was necessary for Miss Crawford to remain in the house last night," she said angrily, to no-one in particular. "She seemed perfectly recovered to me, and in my opinion it is quite intolerable to have such an unnecessary addition to our domestic circle at such a time. But I did, at the very least, presume we would be not be subjected to vulgar and intrusive prying."

"Sister, sister," began Lady Bertram, in a voice weakened by weeping, but Mrs Norris did not heed her, and seized the handle of the door, with an expression of the utmost contempt.

"I beg your pardon," said Mary. "I did not mean — I was looking for Miss Julia’s chamber — "

"I doubt she wishes to see you, any more than we do. Be so good as to leave the house at your earliest convenience. Good morning, Miss Crawford."

And the door slammed shut against her.

Mary took a step backward, hardly knowing what she did, and found herself face to face with one of the footmen; he, like Mrs Chapman, was already dressed in mourning clothes.

"I am sorry," stammered Mary, her face colouring as she wondered how much of Mrs Norris’s invective had been overheard, "I did not see you."

"That’s quite all right, miss," he replied, his eyes fixed on the carpet.

"I was hoping to find Miss Julia’s room. Perhaps you would be so good as to direct me?"

"’Tis at farther end of t’other wing, miss. By the old school-room."

"Thank you."

The footman bowed and hurried away in the opposite direction, without meeting her eye, and Mary stood for a moment to collect herself, and still her swelling heart, before continuing on her way with a more purposeful step.

Nearing the great staircase, she became aware of voices in the hall below, and as she came out onto the landing, she was able to identify them, even though the speakers were hidden from her view by a curve in the stairs. It was Edmund, and Tom Bertram.

"It is scarcely comprehensible!" Edmund was saying. "To think that that all this time we have been thinking her run away — blaming her for the ignominy of an infamous elopement — and yet all the while she was lying there in that dreadful state, not half a mile from the house. It is inconceivable — that such an accident could have happened — "

"My dear Edmund," interjected Tom, "I fear you are labouring under a misapprehension. You were absent from Mansfield, and cannot be expected to be aware of precise times and circumstances, but I can assure you that the work on the channel commenced some hours, at least, after Fanny was missed from the house. It is quite impossible that there could have been such an accident as you have just described."

There was a pause, and Mary heard him pace up and down for a few moments before speaking again. She had already drawn a similar conclusion; moreover, she had private reasons of her own for believing that the corpse she had seen could not have lain above a day or two in the place where it was found.

"And even were that not the case," continued Tom, "you cannot seriously believe that the injuries we were both witness to, were solely the result of a fall? You saw it, as much as I did. Surely you must agree that there was a degree of malice — of deliberation — in the reckless damage done to — " he hesitated a moment. "In short, it can only have been the work of some insane and dangerous criminal. It is of the utmost importance that we arrange at once for a proper investigation."

"But the constable — "

" — has done everything in his power, but even were he a young man, which he is not, he has neither the men nor the authority to pursue the rigorous enquiries demanded by such an extraordinary and shocking case. You must see that — just as you must acknowledge that we have only one course available to us."

"Which is?"

"To send for a thief-taker from London. Mr Holmes himself as good as begged me to do so — he knows as well as I do, that this is our best, if not our only, hope."

"A thief-taker?" gasped Edmund. "Good God, Tom, most of those men are little more than criminals themselves! I have read the London newspapers, and I know how they operate. Bribery, violence, and extortion are only the least of it. Do we really want to open our most private and intimate affairs to such a man? To the public scrutiny such a course of action must inevitably occasion? I beg you, think again before you take such a perilous and unnecessary step."

"Unnecessary?" replied Tom coldly. "I am afraid I cannot agree. You, of all people, must want the villain who perpetrated so foul a deed to be brought to justice? And there is but one way we can hope to achieve that. I have made careful enquiries, and have received a most helpful recommendation from Lord Everingham. His lordship has suffered a number of fires on his property, and this man was instrumental in the discovery and detention of the culprit."

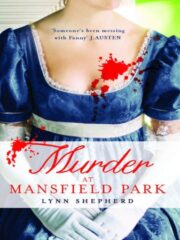

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.