"I hope you will soon receive more encouraging news from Cumberland," she said, regretting she could think of nothing more to the purpose, but relieved to see the girl’s face lighten for a moment at her words.

"It is very good of you to come. I have some satisfaction in knowing that Edmund will soon be at my father’s side — it will be such a relief to us all! As it is, we do not seem to know what to do with ourselves. My aunt has been scolding me all morning about the needlework for Fanny’s wedding, but I can hardly see to sew."

At this, her eyes filled with tears once more, and she turned her face away and began to weep silently. Mary took her hand in her own, and offered her assistance, but it was not without a wondering reflection that she might find herself helping to adorn wedding-clothes for the very woman who was to marry the man she herself loved.

They drank their chocolate in heavy silence, until the stillness of the room was suddenly broken by the sound of violent screams from another part of the house. In a residence of such elegance, tranquillity, and propriety, such a disturbance would have been unusual at any time, but doubly shocking in a house silenced by sorrow. Mary was on her feet in an instant, and going quickly to the door she flung it open, and went to the foot of the staircase. There was no mistake; the noise was issuing from one of the rooms above, and the briefest of glances at the footmen was enough to confirm that this was not the first burst of feeling from that quarter they had witnessed that day. Miss Price was giving vent to tumults of passionate hysterics, and although Mary could not distinguish the words, it was clear that Mrs Norris was doing her utmost to comfort and quiet her. Mary was surprised, and not a little ashamed, wondering for a moment whether she had misjudged Fanny, and formed an unjust estimate of her fondness for her uncle. She felt the indelicacy of listening unseen to such a private grief, and turned back towards the drawing-room, where Maria was standing at the open door. Mary felt her face glow, as if she had been caught in the act of spying, but when she saw the expression of the young woman’s face she quickly forgot her own embarrassment. She doubted if Maria was even aware of her presence; she was wrapped in her own meditations, her cheeks were flushed, and her eyes unnaturally bright.

"Are you quite well, Miss Bertram?" Mary asked gently.

Maria roused herself with some difficulty from her reverie. "Perfectly well, thank you, Miss Crawford," she said coolly. "As far as one can be, in such a situation."

Mary returned to the drawing-room to take her leave of the other ladies, and she was half way across the park before recollecting that she had not asked Julia what she had wished to discuss with her at Compton: every other consideration had been swept away by the news from Cumberland. There was nothing to be done now but to return to the parsonage, and endeavour to find an opportunity to speak to Julia the following day. The rain began to fall once more, and she quickened her pace, noticing, however, that there seemed to be a group of workmen with mattocks gathered around a man on horseback, some distance away. The light was uncertain, but she thought she could discern the figure of her brother, and as she was drying herself in the vestibule, he came in behind her, dripping with wet.

"I have just been giving the men instructions to commence the felling of the avenue, and the digging of the channel for the new cascade," he said, as he shook out his coat. "How do they go on at the Park?"

Mary sighed, and related the events of the afternoon, too preoccupied, perhaps, with her wet shoes to notice the look in his eye as she described what she had heard on the stairs. "I had not expected her to be so affected," she concluded.

"I suppose it rather depends what exactly she is affected by," observed Henry, deep in his own thoughts.

At that moment Mrs Grant appeared, armed with dry clothes, and the promise of hot tea and a good fire.

"I hear there is still no news of Sir Thomas," she said."Poor man! To be cut off at his time of life, when Lady Bertram depends on him so completely! But then again, I have no doubt Mrs Norris will be more than ready to step forward, and supply his place. She never misses an opportunity to interfere, even where she is not wanted. Did you see her at the ball? Taking it on herself to make up the card-tables, as if she were the hostess, and plaguing the life out of the chaperons because she wanted them moved to another part of the room. But at least we will not have to endure all that again in a hurry. There will be no more balls at Sotherton for the present."

Henry looked up from where he was sitting removing his boots. "What is this? No more balls at Sotherton? Do not ask me to believe that Mr Rushworth has all of a sudden lost his taste for gaudy display, or acquired a preference for the modest and discreet."

"No, indeed, Henry," said Mrs Grant, with a look that was only half reproving. "But I heard this morning that he has left the neighbourhood. I am told that when he returned to Sotherton last night, there was a letter awaiting him from his father requesting his presence in Bath, and his father’s requests are not, apparently, of the kind to be trifled with. They say he will not be back before the winter. Did you not hear about it at the Park, Mary? Mr Rushworth called there this morning, on his way to the turnpike road — or so Mrs Baddeley told me. The ladies must have heard the news by now."

"I am certain they have," thought Mary, "and I do not doubt that it was this news, unexpected and unwelcome as it must have been, that was the real cause of Miss Price’s hysteria, rather than any excessive solicitude for her uncle’s health." A glance at her brother proved that he was of much the same mind, but Henry refused to meet her gaze, and a moment later he was on his feet, and hurrying away to dress for dinner.

Chapter 9

The weather worsening the next day, Mary was forced to give up all notion of a walk to the Park, and resigned herself to the probability of twenty-four hours within doors, with only her brother and the Grants for company. In the latter, however, she was mistaken. They were just beginning breakfast when a letter arrived for Henry; a letter of the most pressing business, as they soon discovered.

"It is from Sir Robert Ferrars," he said, as he turned the pages. "You remember, Mary? I had the laying out of his pleasure-grounds at Netherfield last year, after he acquired the estate from Charles Bingley. A small job, hardly worth the trouble, but one that obtained for me some invaluable new connections. Indeed, I still have hopes of a commission at Bingley’s new property on the strength of his recommendation. However," he continued, his brow contracting, "it seems that an officious gardener has been interfering with the drains, with the result that most of the gravel walks are now under half a foot of water. Ferrars is reluctant to entrust the repair work to anyone but me — as well he should be, in the circumstances." He folded the letter and put it carefully in his pocket-book. "He writes to request my presence without delay. I will pen a note to Bertram to inform him, if you would be so good as to send one of the men to the Park? The affair requires my immediate departure, and if the weather is at all the same in Hertfordshire as it is here, I dare not imagine the dirt and disorder I will find on my arrival. It will be a miracle if my magnificent statues are not up to their knees in mud."

The rest of the morning was devoted to packing Henry’s trunk, and preparing for his journey. When the whirl of departure was over, and they had watched him disappear into the mist and gloom of the afternoon, Mary returned to the parlour to warm herself by the fire, and reflect on the slow monotony of a wet day in the country, with nothing but the prospect of cribbage with her brother-in-law to enliven it.The only slight communication from the Park was a short note from Tom Bertram by way of reply to Henry, but it contained no further tidings from Cumberland, and consideration for the footman standing shivering in the dark at the outer door prevented Mary from sending any word to Julia. She would have to wait for better weather, and as she was used to walking, and had no fear of either path or puddles, she was confident that she, at least, would not be too long confined to the house.

However, in this, she was to be disappointed. It was a further four days before even Mary could venture outdoors, four days that brought no further news, either from the Park, or from Henry, though in truth she had not expected a letter from her brother so soon. The next day was Sunday, and a brief cessation in the rain making it possible to attend church in the morning, Mary was in eager expectation of the Bertram carriage at the sweep-gate. She had no great hope of Lady Bertram, but the sight even of Mrs Norris would be a relief after so many days without seeing another human creature besides themselves; and while Mary’s sympathy was for Sir Thomas’s wife and children, she could not but acknowledge that his sister-in-law might prove a more useful and communicative source of intelligence.

The church was crowded — especially so, given the unfavourable weather — and it soon became apparent that all the lookers-on of the neighbourhood had heard of Sir Thomas’s misfortune, and hoped, like Mary, to gain some further news as to his condition. Mary felt ashamed to be part of such a general and importunate inquisitiveness, and all the more so, when she saw Julia Bertram being hurried to the family pew by her aunt, to the audible whisperings of the rest of the congregation. A brief exchange of civilities was all that was possible before the service, and Mary was relieved to find that Dr Grant made no reference to the events at the Park in his sermon, and the text for that Sunday was mercifully insipid; in Mary’s experience, Holy Writ had an unpleasant habit of being only too horribly appropriate.

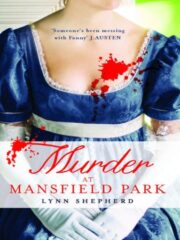

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.