The last arrival was soon followed by tea, a ten miles’ drive home allowing no waste of hours, and from the time of their sitting down, it was a quick succession of busy nothings till the carriage came to the door. It was a beautiful evening, mild and still, and the drive was outwardly as pleasant as the serenity of nature could make it; but it was altogether a different matter to the ladies within. Their spirits were in general exhausted — all were absorbed in their own thoughts, and Fanny and Maria in particular, seemed intent on avoiding one another’s eye. The party stopped at the parsonage to take leave of the Crawfords, and then continued on to the Park, where Mr Rushworth was invited to come in and take a glass of wine, before resuming the journey to Sotherton. But the company had scarcely entered the drawing-room when Lady Bertram rose from the sopha to meet them, came forward with no indolent step, and falling on her son’s neck, cried, "Oh, Tom, Tom! What are we to do?"

Chapter 8

Nothing can convey the alarm and distress of the party. Sir Thomas was dead! All felt the instantaneous conviction. Not a hope of imposition or mistake was harboured any where. Lady Bertram’s looks were an evidence of the fact that made it indisputable. It was a terrible pause; every heart was suggesting, "What will become of us? What is to be done now?"

Edmund was the first to move and speak again. "My dear madam, what has happened?" he asked, helping his aunt to a chair, but Lady Bertram could only hold out the letter she had been clutching, and exclaim in the anguish of her heart, "Oh, Edmund, if I had known, I would never have allowed him to go!"

Entrusting Lady Bertram to her daughters’ care, Edmund turned quickly to the letter.

"He is not dead!" he cried a moment later, anxious to give what immediate comfort was within his power. Julia sat down in the nearest chair, unable to support herself, and Tom started forward, saying, "Then what is the matter? For God’s sake, Edmund, tell us what has happened!"

"He is not dead, but he is very ill. The letter is from a Mr Croxford, a physician in Keswick. It appears my uncle elected to undertake an inspection of the property on horseback, and suffered a dreadful fall, and a serious contusion to his head. It was some hours before he was missed, and several more before he was discovered, by which time he was unconscious, and very cold, and had bled a good deal. This Mr Croxford was sent for at once, and initial progress was good. That afternoon he opened his eyes — "

"So he is better — he is recovered!" cried Julia in all the agony of renewed hope.

" — but soon closed them again, without apparent consciousness, and by the evening he was alternating between fits of dangerous delirium in which he scarce knew his own name, and moments of lucidity, when he seemed almost himself. At the time of writing, Mr Croxford admits that the signs are still alarming, but he talks with hope of the improvement which a fresh mode of treatment might procure. “Before he sank into his present wildness,”" Edmund continued, his voice sinking, "“Sir Thomas begged me to ensure that this letter should go to Mansfield at once, and by private messenger. Knowing himself to be in danger, and fearing that he may never see his beloved family again, he demanded a promise from me, with all the strength and urgency which illness could command, that I would communicate to you his wish, perhaps his dying wish — ”"

Edmund stopped a moment, then added, in a voice which seemed to distrust itself, "I think, perhaps, that it would be better if we deferred the discussion of such a subject until tomorrow — it is a matter of some delicacy."

Mr Rushworth offered at once to withdraw, but Miss Bertram stopped him, saying, "What is it, Edmund? What are my father’s wishes?"

"Very well," said Edmund, with resignation. "Mr Croxford writes as follows: “Sir Thomas directs that there should no longer be any delay in the celebration of the marriage between his niece and Mr Norris. If he should be doomed never to return, it would give him the last, best comfort to know that he had ensured the happiness of two young people so very dear to him. He only wishes that he could be sure that his own children were as nobly and as eligibly settled.”"

Every eye turned upon Miss Price, who, conscious of their scrutiny, rose to her feet and said in an unsteady voice, "You must excuse me, indeed you must excuse me," before running out of the room.

Mrs Norris made to follow her, unable to suppress a look of triumph and exultation at such an unlooked-for resolution to all her difficulties, but Edmund firmly prevented her. "She is distressed, madam. It will all be better left until tomorrow, when we will have had the advantage of sleep. In the mean time, Mr Rushworth, I would be most grateful if you would assist us in keeping the whole affair from public knowledge for the time being, until we receive further news."

Mr Rushworth readily assured them of his secrecy, expressed his sorrow for their suffering, and requested their permission to call the following morning, before taking his leave.

The evening passed without a pause of misery, the night was totally sleepless, and the following morning brought no relief. Those of the family who appeared for breakfast were quiet and dejected; Tom was the only one among them who seemed disposed for speech, wondering aloud how he would ever be able to assume all his father’s responsibilities.

"Someone must speak to the steward, and then there is the bailiff," he said, half to himself, "and of course there are the improvements. I will walk down to the parsonage this morning and see Crawford myself. He should know immediately. I think we may safely confide in the Crawfords. Knowing my father, as they do, they will be genuinely distressed at this dreadful news."

The Grants were not at home, but the Crawfords received the news with all the sympathy and concern required by such painful tidings; Mary had barely comprehended the consequences of his disclosure, and Henry was still expressing their wishes for a happier conclusion to his father’s illness than there was at present reason to hope, when Mr Bertram threw them into even greater amazement.

"I am grateful for your kind condolences, which I will convey to my mother and sisters," he said, "and if Miss Crawford were to favour them with her company at the Park tomorrow, I am sure they would be thankful for any assistance she might be able to offer with the preparations. Though needless to say, we intend to keep matters within a much smaller circle than was originally intended."

He stopped, seeing their looks of incomprehension. "Forgive me, my thoughts are somewhat distracted. But everything considered, I see no reason why you should not know. Sir Thomas has expressed his wish that the marriage between Edmund and Fanny might take place at once. Indeed I was hoping to see Dr Grant, that I might consult him about the service."

"I see," said Mary, rising from her chair and going over to her work-table to hide her perturbation.

"So Miss Price and Mr Norris are to marry at last," said Henry, with studied indifference. "And when, precisely, are we to wish them joy?"

"As soon as Edmund returns. He left this morning for Cumberland. In the mean time, we await further news," he concluded, in a more serious tone, "but I fear that the next letter may simply confer an even greater obligation upon us to hasten the accomplishment of my father’s wishes."

Mr Bertram departed soon after, and Henry following him out, Mary was left alone. Her mind was in the utmost confusion and dismay. It was exactly as she had expected, and yet it was beyond belief!

"Oh, Edmund!" she said to herself. "How can you be so blind! Will nothing open your eyes? Surely Sir Thomas would not insist on this wedding if he knew your true feelings! Or those of his niece! Oh! If I could believe Miss Price to deserve you, it would be — how different would it be! But it is all too late. You will marry, and you will be miserable, and there is nothing anyone else can do to prevent it."

The agitation and tears which the subject occasioned brought on a head-ache. Her usual practice under such circumstances would be to go out for an hour’s exercise, but she dreaded meeting anyone from the Park, and took refuge instead in her room. In consequence, her head-ache grew so much worse towards the evening that she refused all dinner, and went to bed with her heart as full as on the first evening of her arrival at Mansfield.

The next morning brought no further news, and her headache easing, Mary prepared herself to fulfill her promise, and pay a visit to the ladies of the Park. It was a miserable little party. Lady Bertram was a wretched, stupefied creature, and Julia was scarcely less an object of pity, her eyes red, and the stains of tears covering her cheeks. Maria Bertram was by far the most animated of the three, but hers was the animation of an agitated and anxious mind. Fear and expectation seemed to oppress her in equal degrees, and she was unable to keep her seat, picking up first one book and then another, before abandoning both to pace impatiently up and down the room. There was no sign of Fanny, and when Mary made a brief enquiry she was told merely that Miss Price was indisposed, and Mrs Norris was attending to her.

Mary sat for some minutes more in silence, impatient to be gone, but constrained by the forms of general civility, until the appearance of Baddeley with a tray of chocolate, which, by rousing Lady Bertram to the necessity of presiding, gave her the opportunity to speak privately to Julia.

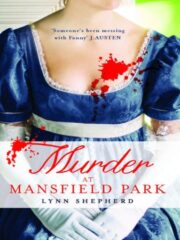

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.