"Capital, my dear Crawford! I was just saying to the ladies, you have out-Repton’d Repton! We are all anticipating the view of the house with the keenest enthusiasm."

They turned in at the lodge and found themselves at the bottom of a low eminence overspread with trees. A little way farther the wood suddenly ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by the house. It was a handsome brick building, backed by gently rising hills, and in front, a stream of some natural importance had been swelled into a series of small lakes, by Henry’s skill and ingenuity. The barouche was stopped for a few minutes, and the three gentlemen rode up to join them. Mary’s heart swelled with pride and pleasure, to see her brother’s genius and taste realised in the beauties of a landscape such as this. Even Mrs Norris was forced into admiration, though evidently against her will. "I wish my dear husband could have seen this," said she. "It is quite like something we had planned at the White House."

Henry was excessively pleased. If Mrs Norris could feel as much as this, the inference of what the young ladies must feel was indeed gratifying. He glanced at Miss Price, to see if a word of accordant praise could be extorted from her, but although she remained resolutely silent, his spirits were in as happy a state as professional pride could furnish when they drove up the last stretch of road to the spacious stone steps before the principal entrance.

The housekeeper met them at the door, and the particular object of the day was then considered. How would the ladies like — in what manner would they choose — to take a survey of the grounds?

"I wonder," said Mr Crawford, looking round him, "whether the party would be interested in an account of the improvements so far? Seeing the park as it is now, it is difficult to imagine it as it was. Shall we summon a council on the lawn? And what does Miss Julia say?" he continued more gently, turning to where she stood at the edge of the party. "How should you like to proceed?"

Julia did not at first appear to have heard, but when Mary touched her gently on the arm she roused herself, and acknowledged in a sad voice, "I suppose I am here to be persuaded, and I cannot give my approbation without knowing how it has been altered."

"Very well," began Henry. "Since I came to Compton we have turned the whole house to front the south-west instead of the north — the entrance and principal rooms, are now on that side, where the view, as you saw, is very fine. The approach was moved, as Mr Rushworth described, and this new garden made at what is now the back of the house, which gives it the best aspect in the world."

"You speak of turning the house with as much ease as I might turn my horse!" cried Tom. "Crawford, is there no limit to your exertions in pursuit of your object?"

"Indeed not," replied Henry, with a look at Miss Price, who affected not to notice. "My role is to improve upon nature, to supply her deficiencies, and create the perfect prospect that should have been from the imperfect one that is."

"A trifling ambition, upon my word!" rejoined Tom. "I will remember to call upon your services when I want a river diverted, a hill removed, or a valley levelled."

"All feats which I have indeed performed!" laughed Henry. "But, to conclude my narration, the meadows you can just see beyond the wilderness have all been laid together in the last year.The wilderness on the right hand was already here when I came — it had been planted up some years before. As such it is further advanced than much of the planting in the new garden, and I commend it to you as not only a pretty walk, but the one affording the best shade on a hot day."

No objection was made, but for some time there seemed no inclination to move in any direction, or to any distance. All dispersed about in happy spontaneous groups, though there was, perhaps, a degree of premeditation in Mrs Norris’s determination to accompany Mr Rushworth and Fanny. For her part, Mary made sure to keep close to Julia, who had relapsed once again into silence and sadness. A moment later she found, to her surprise, that Mr Norris intended to join them, and the three began with a turn on the lawn. A second circuit led them naturally to the door which Henry had told them opened to the wilderness; from there a considerable flight of steps landed them in darkness and shade and natural beauty, compared with the heat and full sunshine of the terrace. For some time they could only walk and admire, and Mary saw at once that the felling of the trees in the park had indeed opened the prospect in a most beautiful manner, even if she forbore from voicing this opinion aloud. At length, after a short pause, Julia turned to Mary and said, "I suppose it must be my late illness that makes me so tired, but the next time we come to a seat, I should be glad to sit down for a little while."

"My dear Julia," cried Edmund, immediately drawing her arm within his, "how thoughtless I have been! I hope you are not very fatigued. Perhaps," turning to Miss Crawford, "my other companion may also do me the honour of taking an arm."

"Thank you, but I am not at all tired." She took it, however, as she spoke, and the gratification of doing so, of feeling such a connection for the first time, assailed her with satisfactions very sweet, if not very sound. A few steps farther brought them out at the bottom of the walk and a comfortable-sized bench, a few yards from an iron gate leading into the park, on which Julia sat down.

"Why would you not speak sooner, Julia?" said Edmund, observing her.

"I shall soon be rested," said Julia quickly. "Pray, do not interrupt your walk. I will be quite comfortable here."

It was with reluctance that Edmund suffered her to remain alone, but Julia eventually prevailed, and watched them till they had turned the corner, and all sound of them had ceased.

A quarter of an hour passed away, and then Miss Bertram unexpectedly appeared on another path, some distance away. She was walking quickly, and with some purpose, and did not seem to notice her sister, or have the slightest notion that any other person was nearby. Julia was about to rise and greet her, when she saw with some surprise that Maria was intent on concealing herself behind a large shrub on one side of the path, to the very great danger of her new muslin gown. The reason for this unaccountable behaviour was soon revealed. Julia heard voices and feet approaching and a few moments later Mr Rushworth and Miss Price issued from the same path, and came to a stop before the iron gate. They had clearly been engaged in a most earnest conversation; Miss Price looked all flutter and happiness, and the faces of both were very close together. Neither was sensible of Miss Bertram’s being there, nor of Julia sitting motionless on the bench only a short distance away. It struck the latter all of a sudden as being more like a play than anything she had seen in the theatre at Mansfield Park, and though she knew she ought to draw their attention to her presence, something constrained her, and she remained fixed in her seat. The first words she heard were from her cousin, and were to this effect.

"My dear Mr Rushworth, I have not the slightest interest in attempting to find Mr Norris. Why, we have but this moment escaped from his horrible mother. No — I have had quite enough of that family for one morning. After all, what is Mr Norris to me that I should get myself hot and out of breath chasing about the garden looking for him?"

"Your words interest me inexpressibly, Miss Price," said Mr Rushworth, with some earnestness. "I had no idea, when I first came into the area, but that you were the intended, indeed the engaged, bride of that very same Mr Norris. A steady respectable sort of fellow, no doubt, but no match for a woman of character and brilliance such as yourself."

"Mr Tiresome Norris bores me more than I can say," said Miss Price with feeling. "So dull, so wretchedly dull! He pays no compliments, he has no wit, and if that were not bad enough, his taste in dress is deplorable, and he has no refined conversation; all he wants to do indoors is talk about books, and all he ever does outside is ride. A deadly tedious life mine would be with the oh-so-estimable Mr Norris."

Mr Rushworth laughed knowingly. "Perhaps Mr Norris has recently found someone who might share these dreary interests of his?"

Miss Price gave him a look which marked her contempt. "She is welcome to him. A woman who has the audacity to attach herself to a man already promised to another, as she has done, will surely have no scruple in taking up that other’s cast-offs."

"And you, my dear — my very dear Miss Price," said he, leaning still closer, "what will you now do? There must surely be countless suitors contending for the honour of your hand."

Miss Price drew away slightly, and began to circle the small glade before the gate. "Not so many as you might imagine, sir. But I have no doubt of acquiring them, once it becomes known that the engagement with Mr Norris is broken off."

"So if there happened to be another gentleman who professed the most sincere attachment to Miss Price — nay, not merely an attachment but the most ardent, disinterested love — it might be as well for that gentleman to declare himself without delay?"

Miss Price looked at him haughtily. "It might be as well for that gentleman to begin by demonstrating, beyond question, that all those ardent feelings are for Miss Price, and not for Miss Bertram."

"My dear Miss Price," he cried, making towards her,"how could you even imagine — you are so infinitely her superior. In beauty, in spirit, in — "

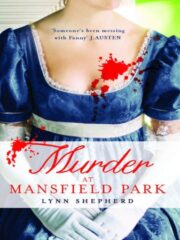

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.