Mr Norris looked her in the face for the first time, seemed about to speak, but then stopped, his eyes fixed intently on her.

"Good heavens," he exclaimed. "What is this? What can be meant by it?"

To Mary’s astonishment, his complexion became pale, and the disturbance of his mind was visible in every feature. Nothing could explain such a complete change of humour and countenance; he had always been polite, even if rather quiet and reserved, but now he made every effort to avoid her eye, and every subject of conversation she attempted was firmly and resolutely repulsed, with the result that they concluded their two dances in a most unpleasant and uncomfortable silence.

As soon as the set was ended Mr Norris made the briefest of bows and walked quickly away towards Rushworth and Miss Price, leaving Mary quite at a loss as to how to proceed. She made her way slowly back to where her brother was standing on the other side of the room, watching the group by the fire in a fit of jealous agitation. Miss Price had refused to dance with him, despite the conspicuous encouragement he believed he had received when they last met at the Park.

"It appears I was a useful distraction for an hour or two," he said, with evident irritation, "but now she has once again succeeded in attracting the attention of that chattering coxcomb Rushworth, I am no more use to her." Mary had feared it would be so, and was about to express her sympathy when they were accosted by Mrs Norris.

"Well, miss," she said loudly, "it has been quite clear to me, from the very day you arrived in the neighbourhood, that you Crawfords are just the sort of people to get all you can, at other people’s expense — but I had not thought even you capable of stooping quite so low."

"I–I — " stammered Mary, her face like scarlet.

"Mrs Norris," said Henry coldly, "I beg leave to interject on my sister’s behalf. To what do you allude, ma’am?"

"That necklace," she replied, "belongs to Miss Price. I am therefore at a loss to imagine how your sister can have come by it."

"I can assure you, ma’am," said Mary, recovering herself, "that the necklace was a kind gift, most freely given."

"I beg your pardon," replied Mrs Norris, "but I cannot quite believe you. Fanny would never have presented you with any item of the slightest value. The cost alone makes such a thing unthinkable. I know for a fact its price was at least eighteen shillings."

Henry was too angry to speak; but Mary stood her ground, and quietly explained the circumstances of the gift. Mrs Norris was, at length, satisfied, if being forced to concede an ill-founded accusation, formed on mistaken premises, may be termed satisfaction, and without making any apology for her error, hastened away. Mary immediately expressed a wish for the relative seclusion of the supper-room, and she was soon after joined by Henry, who, sitting down next to her with a look of consciousness, said, "My own cares are vexing enough, but I am very sorry if anything has occurred to distress you. This ought to have been a day of happiness."

"Oh! It shall be. It is," said Mary, making an effort for her brother’s sake. "Let us say no more about it, I entreat you. I shall have forgotten the whole affair by morning."

"I fear it may prove more enduring than that," he replied in a low voice. "Just now, when I was with them, I heard Norris asking Miss Price about the necklace."

"Mr Norris?" asked Mary, the colour rushing to her face.

"The very same. That necklace you are wearing was evidently his gift."

The truth rushed on Mary in an instant; all of Mr Norris’s unaccountable conduct in the ball-room was now explained; his surprise, his seemingly unintelligible words, and the way he had looked at her, that was fully accounted for by the extraordinary spectacle of a gift he had presented to one woman being conspicuously displayed around the throat of another.

"I must find an opportunity to explain," she said, in distracted tones, rising from her chair. "I must speak to him instantly, I cannot let him think that I — "

"My dear Mary," replied Henry, detaining her, "you have not heard the end of my story. When Miss Price gave no immediate answer to his question, Mrs Norris hastened to explain to him that your necklace is, in fact, an entirely different ornament, of a similar pattern to the one he gave Fanny, but — and here I had difficulty in holding my peace — of inferior workmanship."

"But why?" stammered Mary. "What can be the justification for such an unnecessary deception?"

"Perhaps because Mrs Norris’s beady little eyes have detected some part of the truth? That Miss Price no longer cares for her son — that is, if she ever did — and her making his gift over to you is proof of that. But, one thing you may be sure of — one thing we may both be sure of," this with a look of meaning, "is that old Mother Norris will not let it go as easily as that. That marriage is the favourite project of her heart, and she will do anything necessary to secure it — even if it means practising deceit on her own son."

"But why should Fanny do such a thing?" said Mary. "She must have known the effect it would produce on Edmund — Mr Norris. I can quite believe that she would connive most happily at anything that caused me embarrassment, but what can she hope to gain by behaving so discourteously to Mr Norris? What can be her motive?"

"I do not pretend to understand Miss Price," said Henry grimly, "but could it be that she wishes to put his affection to the test? Or to ascertain if he has feelings for another?"

He stopped. By this time Mary’s cheeks were in such a glow, that curious as he was, he would not press the article farther.

"I do not like deceiving Mr Norris," said Mary after a few moments, oppressed by an anguish of heart.

Henry sighed, and took her hand. "But unless you propose to undeceive him, and therefore to contradict Mrs Norris (which would cause no end of vexation, and not least to you, my dear Mary), then I do not see how it is to be avoided."

In such spirits as Mary now found herself, the rest of the evening brought her little amusement. She danced every dance, though without any expectation of pleasure, seeing it only as the surest means of avoiding Edmund. She told herself that he would soon be gone, and hoped that, by the time of his return, many days hence, she would have succeeded in reasoning herself into a stronger frame of mind. For, although she could see that, contrary to his earlier reserve, he now very much wished to speak to her, she could not yet bear the prospect of listening politely to apologies that had been extorted from him by falsehood.

Chapter 6

The house was very soon afterwards deprived of its master, and the day of Sir Thomas’s departure followed quickly upon the night of the ball. Only the necessity of the measure in a pecuniary light had resigned Sir Thomas to the painful effort of quitting his family, but the young ladies, at least, were somewhat reconciled to the prospect of his absence by the arrival of Mr Rushworth, who, riding over to Mansfield on the day of Sir Thomas’s leave-taking to pay his respects, renewed his proposal for private theatricals. However, contrary to Miss Price’s more sanguine expectations, the business of finding a play that would suit every body proved to be no trifle. All the best plays were run over in vain, and Othello, Macbeth, The Rivals, The School for Scandal, and a long etcetera, were successively dismissed.

"This will never do," said Tom Bertram at last. "At this rate, my father will be returned before we have even begun. From this moment I make no difficulties. I will take any part you choose to give me."

At that moment, Mr Yates took up one of the many volumes of plays that lay on the table, and suddenly exclaimed, "Lovers’ Vows! Why not Lovers’ Vows?"

"My dear Yates," cried Tom, "it strikes me as if it would do exactly! Frederick and the Baron are capital parts for Rushworth and Yates, and here is the rhyming Butler for me — if nobody else wants it. And as for the rest, it is only Count Cassel and Anhalt. Even Edmund may attempt one of them without disgracing himself, when he returns."

The suggestion was highly acceptable to all; to storm through Baron Wildenhaim was the height of Mr Yates’s theatrical ambition, and he immediately offered his services for the part, allowing Mr Rushworth to claim that of Frederick with almost equal satisfaction. Three of the characters were now cast, and Maria began to be concerned to know her own fate. "But surely there are not women enough," said she. "Only Agatha and Amelia. Here is nothing for Miss Crawford."

But this was immediately opposed by Tom Bertram, who asserted the part of Amelia to be in every respect the property of Miss Crawford, if she would accept it. A short silence followed. Fanny and Maria each felt the best claim to Agatha, and was hoping to have it pressed on her by the rest. But Mr Rushworth, who with seeming carelessness was turning over the first act, soon settled the business. "I must entreat Miss Bertram," said he, "not to contemplate any character but that of Amelia. That, in my opinion, is by far the most difficult character in the whole piece. The last time I saw Lovers’ Vows the actress in the part gave quite the most deplorable performance (and in my opinion, the whole play was sadly wanting — if they had accepted my advice, they might have brought the thing round in a trice, but though I offered my services to the manager, the scoundrel had the insolence to turn me down). But as I was saying, a proper representation of Amelia demands considerable delicacy — the sort of delicacy we may confidently expect from Maria Bertram."

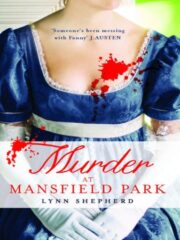

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.