I carry everything to the white room and pry off the lids of the cans with a butter knife: crimson, yellow, cobalt, bubblegum pink, deep purple—like a bruise—and three different greens to match the summer leaves. I stick my hand in the red paint first, and rub my fingertips together. It falls heavy, spilling on my clothes and the floor where I am kneeling. I scoop up more, ‘til my hands are brimming. Then I throw it—a handful of red paint at my white, white wall. Color explodes. It spreads. It runs. I take more—I take all of the colors—and I stain my white room. I stain it with all the colors of Isaac, as Florence Welch sings me her song.

It’s then that my phone rings. I don’t pick it up, but when I listen to the message later that night, Detective soft s Garrison informs me that Saphira is dead. Dead by her own hand. Good, I think at first, but then my chest aches. He doesn’t tell me how she did it but something tells me she opened her own veins. Bled out. She liked her patients to bleed out their thoughts and feelings; she would have chosen to go that way. Saphira and her god-complex would never have tolerated being tried in a court of law. She thought people were stupid. It would have been beneath her to be judged. I call him the next morning. There would be no trial. He sounds disappointed when he tells me, but I feel relieved. It’s an end to the nightmare. I couldn’t have handled months and months of a trial. Wasting my last days seeking human justice. I think I forgive her for believing she was God, I’m not sure God will.

Garrison informs me that there is an ongoing investigation into Saphira’s accomplices. “Everyone we have questioned is shocked. She was well respected in the mental health community. No family in the country. No friends. She seems to have just snapped, lost touch with reality.”

Who has time for friends when you’re performing human experiments? I think.

“What about the blood on the books?” I ask. “Was it human?”

There is a long pause.

“The lab test indicated that it was animal blood. A ram or a goat, we can’t be a hundred percent sure. We found your books in her home, along with your case file from-”

“I figured,” I say quickly.

“There was something else,” he says. “We found the footage of your time in the house.”

I squeeze my eyes closed. “What are you going to do with it?”

“It’ll go into evidence,” he says.

“Good. No one will see it?”

“Not the media, if that’s what you’re asking.”

“Okay.”

“There is one more thing…”

How many more things could there be?

“Saphira had an apartment in Anchorage. We think that’s how she got to you so quickly when Isaac was sick. She had been watching a recording of you and Doctor Asterholder. She was only able to see what was happening in the house when the power was on, and there was only sound in certain rooms. So there are gaps in the recordings. But, it was paused. I was hoping you’d be able to tell me something about the context of what I was seeing.”

“What was it paused on?” I am breathless…sick. It never occurred to me that there were multiple cameras set up around the house.

“You holding a knife to Doctor Asterholder’s chest.”

I lick my lips. “He was holding a knife to his own chest,” I say. My mind is ripping through what exactly Saphira was trying to tell me.

“It was the moment I changed,” I say. “It was the reason she did what she did.”

I look for my mother’s book. I go the local bookstore and detail the plot to a wide-eyed girl of no more than eighteen behind the counter. She calls a manager to the front to help me. He looks at me earnestly while I repeat everything I just said to the girl. When I am finished, he nods like he knows just what I am talking about.

“The book I think you are talking about had a small run on the New York Times Bestsellers List,” he says. I raise my eyebrows to his back as he leads me to the rear of the store and pulls a book off the shelf. I don’t look at it as he hands it to me. I hold the weight of it in my hands and stare blankly at his face. I feel as if I’m about to see my mother face to face.

“You’re the writer, the one who—”

“Yes,” I say. “I’d like some privacy.”

He nods, and leaves me. I have a feeling he’s going to wherever managers go to tell everyone he knows that the kidnapped writer is here.

I take one of those breaths that make you burn on the inside, then I drop my head.

I see the cover—the words, the oranges and teals that make up the pattern of a woman’s dress. You can only see the back of her, but her arms are spread wide, her blonde hair cascading down her back. The Fall.

The fall of my mother. I wonder if she wrote this for me. Is that too much to ask? An explanation for your abandoned daughter … your china doll? My mother is a narcissist. She wrote this for herself, to feel better for leaving me. I flip open the cover and search for a picture on the dust jacket. There is none. I wonder if she’s still pretty. If she still wears flower skirts and headbands. She writes under the name Cecily Crowe. I grin. Her real name was Sarah Marsh. She hated the normalcy of it.

Cecily Crowe lives everywhere.

She does not believe in dogs or cats.

This is her first novel, and probably her last.

I close the book; slide it back into the space it came from. I have no desire to read it again, not even in order with page numbers. I got to know my mother in a discombobulated way. I am her china doll. She mourned me a little, but not enough. I can’t fault her for running—I’ve been running my entire life; bad blood, maybe. Or maybe she taught me, and someone taught her. I don’t know. We can’t blame our parents for everything. I don’t think I care anymore. It’s just the way it is. I walk out of the store. I put her to rest.

Chapter Forty-Two

Three months after I get home, I drive to the hospital to see Isaac. I don’t know if he wants to see me. He hasn’t tried to contact me since I’ve been back. It hurts after the emotional violence we experienced together, but it’s not like I tried to contact him either. I wonder if he told Daphne everything. Maybe that’s why…

I don’t know what to say. What to feel. Relief because we both survived? Do we talk about what happened? I miss him. Sometimes I wish we could go back, and that’s just sick. I feel as if I have Stockholm Syndrome, but not for a person—for a house in the snow.

I pull into a space and sit in my car for at least an hour, picking at the rubber on the steering wheel. I called ahead, so I know he’s here. I don’t know what it’s going to feel like to see him. I held his body while he was dying. He held mine. We survived something together. How do you stand back and shake someone’s hand in the real world when you were clutched together in a nightmare?

I fling open my car door and it cracks against the side of an already beat up minivan. “Sorry,” I tell it, before stepping away.

The doors to the hospital slide open, and I take a moment to look around. Nothing has changed. It’s still too cold in here; the fountain still sprays a crooked stream into air that smells deeply of antiseptic. Nurses and doctors cross paths, charts clutched against chests or hanging droopy from their hands. It all stayed the same while I was changing. I turn my face toward the parking lot. I want to leave, stay out of this world. No one but Isaac knows what it was like. It makes me feel like the only person on the planet. It makes me angry.

I need to talk to him. He’s the only one. I walk. Then I’m in the elevator, sliding slowly up to his floor. He is probably doing rounds, but I’ll wait in his office. I just need a few minutes. Just a few. I walk quickly once the doors open. His office is just around the corner and past the vending machine.

“Senna?”

I spin. Daphne is standing a few feet away. She is wearing black scrubs and a stethoscope is hanging around her neck. She looks tired and beautiful.

“Hello,” I say.

We stand looking at each other for a minute, before I break the silence. I wasn’t expecting to see her. It was stupid. An oversight. I didn’t come here to make her uncomfortable.

“I came to see—”

“I’ll get him for you,” she says, quickly. I am surprised. I watch as she turns on her heel and trots down the hallway. Maybe he didn’t tell her everything.

He won’t speak to the news stations either. My agent called me days after I got back, wanting to know if I could write a book detailing what happened to me—to us. The truth is I don’t know that I’ll ever write another book. And I’ll never tell about what happened in that house. It’s all mine.

When I see him I hurt. He looks great. Not the skeleton man I kissed goodbye. But there are more lines around his eyes. I hope I put a few there.

“Hello, Senna,” he says.

I want to cry and laugh.

“Hi.”

He motions for his office door. He has to open it with a key. Isaac steps inside first and turns on the light. I cast a quick glance over my shoulder before walking in to see if Daphne is lurking anywhere. Thankfully, she’s not. I can’t bear her burdens on top of the ones I’m already carrying.

We sit. It’s not uncomfortable, but it’s not entirely tea and cookies either. Isaac sits behind his desk, but after a minute he comes and sits in the chair next to me.

“You’re back to work,” I say. “Couldn’t stay away.”

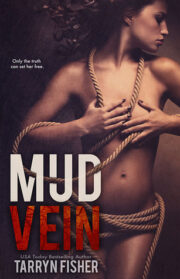

"Mud Vein" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mud Vein". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mud Vein" друзьям в соцсетях.