"Oh, Mr. Knightley, how kind of you to walk with us," said Miss Bates. "I am not surprised Miss

Woodhouse did not enjoy my company - so kind of her to be so forbearing - I rattle on sadly, it must be a trial to her - so good of her to trouble herself to visit me, for I am sure I am always receiving attention from her and her father," she said, as we set out.

And for the rest of the walk, I had to listen to her apologizing for her tongue, when it should have been Emma who was apologizing for hers.

I did what I could to soothe her, and she grew easier. I was just beginning to regain my composure when Mrs. Elton joined us and tried to force Miss Fairfax to take up an appointment with friends of hers. I pity any poor woman who would have to go as a governess to Mrs. Smallwood, no matter how near Maple Grove she might be! This objectionable episode put the seal on a most disagreeable day.

My anger had not cooled when I stood next to Emma as we waited for the carriage to take us home again. I told myself I must not reprimand her or criticize her, but I could not help myself. I could not see her being dragged down, when a word from me might stop it.

"Emma, I must once more speak to you as I have been used to do," I said, in some agitation. Even then, I tried to hold back, but I could not. "I cannot see you acting wrong, without a remonstrance. How could you be so unfeeling to Miss Bates? How could you be so insolent in your wit to a woman of her character, age and situation? Emma, I had not thought it possible."

She blushed, but only laughed.

"Nay, how could I help saying what I did? Nobody could have helped it. It was not so very bad. I dare say she did not understand me."

"I assure you she did. She felt your full meaning. She has talked of it since. I wish you could have heard how she talked of it - with what candour and generosity. I wish you could have heard her honouring your forbearance, in being able to pay her such attentions, as she was for ever receiving from yourself and your father, when her society must be so irksome."

"Oh!" she said airily, "I know there is not a better creature in the world: but you must allow, that what is good and what is ridiculous are most unfortunately blended in her."

"They are blended," I said, "and were she a woman of fortune, I would leave every harmless absurdity to take its chance - but, Emma, consider how far this is from being the case. She is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she lives to old age, must probably sink more. Her situation should secure your compassion. It was badly done, indeed!"

She was not interested. She looked away, impatient with me for speaking to her thus. But I had started, and I could not have done until I had finished.

"To laugh at her, humble her - and before her niece, too. This is not pleasant to you, Emma - and it is very far from pleasant to me; but I must, I will, tell you truths while I can, satisfied with proving myself your friend by very faithful counsel, and trusting that you will some time or other do me greater justice than you can do now."

I handed her into the carriage. She did not even bid me goodbye. She was sullen. Who could blame her? But it could not be helped. I had said what I had to say, and I returned to the Abbey in low spirits.

By and by, the sight of my fields began to restore my sense of calm. The air was sweet with the scent of clover, and the birds were singing. If Emma had been with me, I would have known complete happiness. But she was not, and as I came inside I had to acknowledge that such a thing would never come to pass.

I retired to my room, picked up my quill and gave vent to my feelings. But I cannot forget about Emma. Where is she now? Is she at Hartfield, thinking of Frank Churchill and his easy flattery? She must be. And soon she will be living at Enscombe.

I must go away, at once. I cannot bear to see her with him, to watch her permitting, even encouraging, his attentions. It hurts me too much. She is lost to me. My Emma.

Saturday 26 June

I awoke, firm in my resolve to go away, and settled on London, as it would give me an opportunity to see to some business, and to see John and Isabella.

I could not go without seeing Emma one last time, however, and I walked over to Hartfield. I was out of luck, for Emma was not at home. I meant to be on my way at once, but I sat with Mr. Woodhouse, asking him if he had any message to send to Isabella, then telling him I did not know how long I would be away. I still could not bear to go, not without seeing her for one last time.

Harriet arrived, which provided a diversion, and gave me an excuse to remain awhile longer.

"I hope I find you well?" I said to her, standing up as she entered the room.

She blushed prettily.

"Very well, I thank you," she said.

"I have called to see Miss Woodhouse, to tell her I am going to London, but she is out. I would like to speak to her before I go. I cannot stay above five minutes, however," I said firmly, but my body seemed to move of its own accord and I sat down beside Harriet.

"I should like to go to London," said Harriet. "It must be a wonderful place."

"It is not somewhere I wish to go," I said. "I would much rather stay at home."

She blushed, and I thought again that she must have guessed my secret, and that she knew I did not want to go because I did not want to leave Emma. I was glad of her silent sympathy.

"I hope you will not be away for very long," she said.

It was kind of her to speak to me as though there was hope for me, but I know I have lost Emma. I will never call her mine. Never take her to the Abbey. Never see her sitting opposite me in the evening. Never go with her to London to visit Isabella and John. Never see her playing with our children, as she plays with her sister’s children.

But I had to face it like a man.

I meant to leave, but I could not bring myself to do so. Not without one last glimpse of Emma, and so I continued to talk to Miss Smith.

"Did you enjoy our trip to Box Hill?" I asked her.

"Oh, yes, very much," she said.

"I am glad," I said warmly, and so I was: I was glad that at least one person had enjoyed it.

"I was sorry you ate out of doors," said Mr. Woodhouse anxiously. "Perry did not think it at all wise. I hope you may not take cold."

She assured him she was quite well.

"You were very ill over the winter," he said to her.

"You were indeed," I said kindly, remembering that she had had other ills, besides a cold, to bear.

"It was nothing," she whispered.

I began to think there was more to her colourings than goodwill towards me and my suit, and I wondered if she might have caught another cold after all, for not only did she seem to colour a great deal, but also to whisper.

"I hope your throat is not sore?" I asked her.

"No, thank you," she said, and blushed again.

The time passed slowly, but pass it did, and at last Emma returned. I rose as soon as she came in, saying I was going to London, and asking if she had any message to send to her sister. She looked surprised, but I said I had been planning the expedition for some time.

I waited for a word from her, something to give me hope to remain, but there was nothing.

I was a fool to expect it. To think that Emma, with all her advantages of birth and beauty, with a good heart and superior understanding, would sacrifice the attentions of a man who flatters her for the hand of a man who scolds her! If I had ever had a chance of winning her away from Churchill, I had lost it on Box Hill.

She said she had no particular message, and I was about to leave when her father began asking her about her morning call. To my surprise, I learnt that she had been calling on the Bateses, which is why she had been from home.

I am sure she did not go to apologize - it would have been beyond the desire of either party, for Miss Bates would have been as embarrassed as Emma - but this attention would be recognized as an apology, and I felt my heart expand. So Emma had not lost her better nature!

My face must have showed my thoughts, for she smiled at me, a little shyly, and on an impulse I took her hand. I wanted to do more. I wanted to kiss it. I lifted it, scarcely knowing what I was doing, and I was about to press it to my lips when I recollected that I had no right to do such a thing, no matter how much I might want to.

I dropped her hand, then making her a bow, I bade her and her father farewell. I said goodbye to Harriet, and set out for London.

It was a long and dismal journey, filled with gloomy thoughts, but once I reached Brunswick Square, I endeavoured to put my troubles out of my mind.

John and Isabella were surprised to see me, but I gave some pretext relating to business and they accepted it, welcoming me into their home.

I soon saw that the boys had grown since they were with us in the spring. Henry was turning into a fine boy, and John was not far behind. Bella had grown a very little, except in mischief, and George was still content to toddle behind her. The baby was showing an interest in everything, and I sat down with her on my knee.

Henry asked me about Harriet and the Gypsies, a tale which made Isabella shudder, and John asked me what had been done to make sure the roads were safe. This led to parish business, and we talked of Highbury and Hartfield until it was time to go to bed.

I went upstairs but I could not sleep. I took up my newspaper, but I could not pay attention to it. I was not interested in the world outside, I was interested in my own world, and at the heart of that world was Emma. Emma with her good heart, Emma with her dear face. Emma. My Emma.

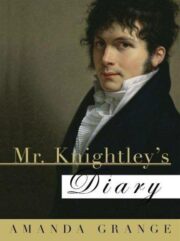

"Mr. Knightley’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Knightley’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Knightley’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.