‘There is no need to be sorry. I did not want to marry you,’ she said.

She smiled, and I was taken aback. There was no timidity in her smile, and as she walked up to me she looked confident and assured.

‘Am I then so terrible?’ I asked.

‘No, not that. As a friend and a cousin I like you very well – as long as the weather is fine, and you are not forced to remain indoors – but I do not love you, and the thought of marrying you made me miserable. I am glad you are to marry Elizabeth. She is in love with you. She will tease you out of your stiffness, and we will all be friends.’

‘She is in love with me? I wish I could be so sure.’

‘One woman in love recognizes another,’ she said.

She smiled again and then followed Lady Catherine out of the room.

I am once again at Netherfield. I arrived here with more hope than I have ever felt, but still I dare not take Elizabeth’s love as a settled thing. Bingley and I left Netherfield early and soon arrived at Longbourn. Miss Bennet was full of blushes and had never looked more becoming. Elizabeth was harder to understand. She, too, blushed. I wish I knew the cause!

Bingley suggested a walk.

‘I will fetch my bonnet,’ said Kitty. ‘I have been longing to see Maria. We can walk to the Lucas’s.’

Mrs Bennet frowned at her, but Kitty did not notice.

‘I am not a great walker, I am afraid,’ said Mrs Bennet, turning to Bingley with a smile. ‘You must excuse me.

But Jane loves to walk. Jane, my dear, fetch your spencer.

That man, I suppose, will go, too,’ she said, looking at me as though I was a disagreeable insect.

Elizabeth blushed. I ignored the remark as best I could, and thought that only my love for Elizabeth could induce me to set foot in that house ever again.

Bingley looked helpless.

‘Lizzy, run and fetch your spencer, too. You must keep Mr Darcy company. I am sure he will not be interested in anything Jane has to say.’

‘I am too busy to walk,’ said Mary, lifting her head from a book. ‘I have often observed that those who are the best walkers are those who lack the intellectual capacity to instruct themselves in the serious matters of life.’

‘Oh, Mary!’ said Mrs Bennet impatiently.

Mary returned to her book.

Elizabeth and her sister returned, having put on their outdoor clothes, and we set out. Bingley and his beloved soon fell behind. Kitty, I knew, would soon leave us to go to visit her friend. Would Elizabeth go too? I hoped not.

If she remained with me, then I would be able to talk to her. And talk to her I must.

We reached the turning to the Lucas’s.

‘You can go on by yourself,’ said Elizabeth. ‘I have nothing to say to Maria.’

Kitty ran off down the path, leaving Elizabeth and me alone.

I turned towards her.

Elizabeth, I was about to say, when she stopped me by speaking herself.

‘Mr Darcy, I am a very selfish creature; and, for the sake of giving relief to my own feelings, care not how much I may be wounding yours.’

I felt myself grow cold. All my hopes now seemed like vanity. She was going to wound my feelings. I had been wrong to read so much into her refusal to deny the report of our engagement. It had meant nothing, except that she would not deign to deny an idle report for the benefit of my aunt.

She was obviously finding it difficult to continue.

She is going to tell me never to come to Longbourn again, I thought. She cannot bear the sight of me. I have given her a disgust of me that is too great to be overcome. I have not used my opportunities. I have visited Longbourn with Bingley and said nothing, because I had too much to say. Yet none of it could have been said in front of others. And now it is too late. But I will not let it be too late. I will speak to her, whether she wants me to or not.

But then she went on, even as those thoughts were going through my mind.

‘I can no longer help thanking you...’

Thanking me? Not blaming me, but thanking me? I scarcely knew what to think.

‘...for your unexampled kindness to my poor sister.’

Unexampled kindness? Then she does not hate me!

The thought made my spirits rise, though cautiously, for I did not know what she had heard of the business, or what else she was going to say.

‘Ever since I have known it, I have been most anxious to acknowledge to you how gratefully I feel it. Were it known to the rest of my family, I should not have merely my own gratitude to express.’

Gratitude. I did not want her gratitude. Liking, yes.

Loving, yes. But not gratitude.

‘I am sorry,’ I said, ‘exceedingly sorry, that you have ever been informed of what may, in a mistaken light, have given you uneasiness. I did not think Mrs Gardiner was so little to be trusted.’

‘You must not blame my aunt,’ she said. ‘It was Lydia who told me of it, and then I asked my aunt for greater detail. Let me thank you again and again,’ went on Elizabeth, ‘in the name of all my family, for that generous compassion which induced you to take so much trouble, and bear so many mortifications, for the sake of discovering them.’

Generous compassion. She thought well of me, but in what way? I was in an agony of suspense.

‘If you will thank me, let it be for yourself alone,’ I said. My voice was low and impassioned. I could not hold my feelings in. ‘Your family owe me nothing. Much as I respect them, I believe I thought only of you.’

I stopped breathing. I had spoken. I had let out my feelings. I had offered them to her, and could only wait to see if she would fling them back in my face. But she said nothing. Why did she not speak? Was she shocked?

Horrified? Pleased? Then hope rose in my breast. Perhaps she was kept silent by pleasure? I had to know.

‘You are too generous to trifle with me,’ I burst out.

‘If your feelings are still what they were last April, tell me so at once. My affections and wishes are unchanged. But one word from you will silence me on this subject for ever.’

It seemed to be an age before she spoke.

‘My feelings are so different…’ she began.

I started to breathe again.

‘…that I am humbled to think you can still love me…’

I began to smile.

‘…now I receive your assurances with gratitude and…and pleasure…’

‘I have loved you for so long,’ I said, as she slipped her hand through my arm and I covered it with my own. To claim her was a joy. ‘I thought it was hopeless. I tried to forget you, but to no avail. When I saw you again at Pemberley I was overcome with surprise, but quickly blessed my good fortune. I had a chance to show you that I was not as mean-spirited as you thought me. I had a chance to show you that I could be a gentleman. When you did not spurn me, when you accepted my invitation, I dared to hope, but your sister’s troubles took you away from me and I saw you no more. I could not let matters rest. I had to help your sister, in the knowledge that by doing so I was helping you. Then, when she was safely married, I had to see you. I was as nervous as Bingley when we arrived at Longbourn. It was clear that your sister was a woman in love, but I could tell nothing from your face or manner. Did you love me? Did you like me? Could you even tolerate me? I thought yes, then I thought no.

You said so little –’

‘Which was not in my nature,’ she said with an arch smile.

‘No,’ I said, returning the smile. ‘It was not. I did not know whether it was because you were displeased to see me or merely embarrassed.’

‘I was embarrassed,’ she said. ‘I did not know why you had come. I was afraid of showing too much. I did not want to expose myself to ridicule. I could not believe that a man of your pride would offer his hand when it had already been rejected.’

‘His hand, no, but his heart, yes. You are the only woman I have ever wanted to marry, and by accepting my hand you have put me forever in your debt.’

‘I will remind you of it, when you are cross with me,’ she said teasingly.

‘I could never be cross with you.’

‘You think not, but when I pollute the shades of Pemberley, it is possible that you might!’

I laughed. ‘Ah yes, my aunt expressed herself forcefully to both of us.’

‘She told me I would never live at Pemberley,’ said Elizabeth.

‘I ought to dislike her for it, but I am too much in charity with her. It is her visit that brought me to you.’

‘She came to see you?’

‘She did. In London. She was in high dudgeon. She told me that she had been to see you, and that she had demanded that you contradict the rumour of our impending marriage. Your refusal to fall in with her wishes put her sadly out of countenance but it taught me to hope.’

I spoke of my letter. ‘Did it,’ I said, ‘did it soon make you think better of me? Did you, on reading it, give any credit to its contents?’

‘It made me think so much better of you, and so immediately, that I felt heartily ashamed of myself. I read it through again, and then again, and as I did so, every one of my prejudices was removed.’

‘I knew that what I wrote must give you pain, but it was necessary. I hope you have destroyed the letter.’

‘The letter shall certainly be burnt, if you believe it essential to the preservation of my regard; but, though we have both reason to think my opinions not entirely unalterable, they are not, I hope, quite so easily changed as that implies.’

‘When I wrote that letter, I believed myself perfectly calm and cool, but I am since convinced that it was written in a dreadful bitterness of spirit.’

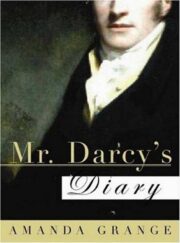

"Mr. Darcy’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.