She thought of Lady Catherine’s visit to Longbourn a few short weeks before, when Lady Catherine had tried to dissuade her from marrying Darcy by saying that she would be censured, slighted, and despised by everyone connected with him, and that the alliance would be a disgrace; that Elizabeth herself, if she were wise, would not wish to quit the sphere in which she had been brought up. To which Elizabeth had replied angrily that, in marrying him, she should not consider herself as quitting her sphere, because Darcy was a gentleman and she herself was a gentleman’s daughter.

And that had been true. But only in Paris had she realised how wide was the gulf between a gentleman’s daughter from a country manor house and a gentleman of Darcy’s standing. The people he knew in Paris were quite unlike the country gentry of England. They were beautiful and mesmerising in a way she had never encountered before. The women undulated, instead of walked, across the rooms with the sinuous beauty of snakes, and the men were scarcely any less seductive. They spoke to her in low voices, holding her hand lingeringly and gazing into her eyes with an intensity which at once attracted and repulsed her.

Nevertheless, she liked Paris, and by the time she arrived at the salon, she was ready to enjoy herself.

The house was insignificant from the outside. It was situated on a dirty street and had a narrow, plain frontage, but once inside everything changed. The hall was high ceilinged and carpeted in thick scarlet, and a grand staircase swept upstairs to the first floor. It was crowded with people, all wearing the strange new fashions of the Parisians. Gone were the elaborate styles of the pre-revolutionary years, with wide hooped skirts and towering wigs. Such signs of wealth had been discarded in fear, and simplicity was the order of the day. The men wore their hair long, falling over the high collars of their coats, and at their necks they wore cravats. Beneath their coats they wore tightly fitting knee breeches. The women wore gowns with high waists and slender skirts, made of a material so fine that it was almost sheer.

There was a noise of conversation as the Darcys began to climb the stair. One or two people raised quizzing glasses so they could stare at Elizabeth. She felt conscious that her dress was English and appeared staid by the side of the Parisian finery. The fabric was sturdier and the style less bare.

Darcy introduced her to some of the people and they welcomed her to Paris, but it was not the warm welcome of Hertfordshire; it was an altogether more appraising greeting.

Elizabeth and Darcy made their way to the top of the stairs where they waited to be announced.

The doors leading to the drawing room had been removed and the opening had been shaped into an oriental arch. It framed the hostess so perfectly that Elizabeth suspected it was deliberate. Mme Rousel, reclining on a chaise longue, was like a living portrait. Her dark hair was piled high on her head and secured by a long mother-of-pearl pin, from which curls spilled artistically round her sculptured features and fell across her bare shoulders. Her dress was cut low, with the small frills which passed for sleeves falling off her shoulders before merging with a delicate matching frill at her neck. The sheer fabric of her skirt was arranged around her in folds that were reminiscent of Greek statuary, and on her feet she wore golden sandals. A dark red shawl was draped across her knees, flowing over the gold upholstery of the chaise longue in an apparently casual arrangement. But every fold was so perfect that its placement could only be the result of artifice and not the negligence it was intended to convey. Elizabeth realised that that was why she felt uncomfortable: because the whole salon, from the people to the clothes to the furniture, was the result of artifice, a carefully arranged surface which shone like the sea on a summer’s day but disguised whatever truly lay beneath.

The Darcys were announced. At the name, many of the people already in the drawing room turned round. Even here in Paris, the name of Darcy was well known. They stared openly, in a way the English would not have done, with a boldness that was unsettling.

They went forward and Mme Rousel, Darcy’s cousin, welcomed them.

‘At last, Darcy, I was wondering when you would pay me a visit. It is many years since I have seen you.’

‘It has not been easy to visit France,’ he said.

‘For one of our kind it is always easy,’ she said reprovingly. ‘But you are here now, and that is all that counts.’

She held out her hand, with its long white fingers covered in rings, and he kissed it. She then withdrew it and placed it precisely in her lap, exactly as it had been before.

‘So you are Elizabeth,’ she said. ‘You must be very special to have won Darcy’s affections. I never thought he would marry. The news has taken many of us by surprise.’ She looked at Elizabeth and then at Darcy and then back again. Her expression was thoughtful. Then she bowed slightly to Elizabeth with a small incline of her head before wishing them joy of her salon.

‘You will find many old friends here and some new ones, too,’ she said to Darcy.

Darcy and Elizabeth moved on into the large drawing room so that Mme Rousel could greet her next guests.

Darcy was at once welcomed by four women who walked up to him with lithe movements and lingering glances. Their dresses were rainbow hued, in the colours of gems, and flimsy, like all the Parisian dresses. Their hair was dark and their skin was pallid.

‘You will have to be careful,’ came a voice at Elizabeth’s shoulder.

She turned to see a man with fine features and tousled hair. He had an air of boredom about him, and although Elizabeth did not usually like those who were easily bored, there was something strangely magnetic about him. His ennui gave his mouth a sulky turn which was undeniably attractive.

‘They will take him from you if they can,’ the man continued, watching them all the while.

Elizabeth turned to look at them, and as she did so, she was reminded of Caroline Bingley and her constant efforts to catch Darcy’s attention. He had been impervious to Caroline and he was impervious to the Parisian women as well, for all their efforts to enrapture him. As they talked and smiled and leant against him, flicking imaginary specks of dust from his coat and picking imaginary hairs from his sleeve, they looked at him surreptitiously. When they saw that he was oblivious to their attempts to captivate him, they redoubled their efforts, one of them whispering in his ear, another leaning close to his face, and the other two walking, arm in arm, in front of him, in order to display their figures.

‘It is not right, what they do there, he being so newly married,’ said a woman, coming up and standing beside the two of them. ‘But forgive me, I was forgetting, we have not been introduced. I am Katrine du Bois, and that is my brother, Philippe.’

There was an air of warmth about the woman which was missing from many of the salon guests, and Elizabeth sensed in her a friend. And yet there was something melancholy about her, as though she had suffered a great disappointment from which she had never recovered.

‘It is not right, no,’ said Philippe. ‘But it is nature. What can one do?’

He turned to look at Elizabeth with sympathy but Elizabeth was only amused.

‘Poor things!’ she said.

Darcy wore the same expression he had worn when she had first seen him at the Meryton assembly; and despite the difference in the two events, the noisy vulgarity of the assembly and the refined elegance of the salon, he was still above his company. His dark hair was set off by his white linen and his well-moulded face, even in such company, was handsome. His dark eyes wandered restlessly over his companions until they came to rest on Elizabeth. And then his face relaxed into softer lines, full of warmth and love.

‘I wish a man would look at me the way that Darcy looks at you,’ said Katrine.

‘I am very lucky,’ said Elizabeth, and she knew that she was.

She had not married for wealth or position; she had married for love. She wished that she was not in company, that she and Darcy had stayed at the inn where they could have been alone, but she knew they would not be in Paris forever. The calls and engagements would come to an end and then they would have more time to spend, just the two of them, together.

‘You are,’ said Katrine. ‘I have many things; I have jewels and clothes, carriages and horses, a fine house and finer furnishings, but I would give them all for one such look.’

Darcy’s companions claimed his attention and he turned reluctantly away. As he did so, his hand moved to his chest as though he were lifting something beneath his shirt, pulling it away from his chest and then letting it drop again.

‘What is it he does there?’ asked Katrine. ‘Does he wear something round his neck?’

‘Yes, I bought him a crucifix yesterday. The shops in Paris are very tempting,’ said Elizabeth. ‘He refused to take it at first, but he had given me so much and I had given him so little that I insisted, and at last he allowed me to fasten it around his neck.’

Katrine’s voice was reverent. ‘He must love you very much,’ she said.

‘Yes, I believe he does,’ said Elizabeth.

‘And now, we have talked of Mr Darcy for long enough,’ said Philippe. ‘Any more and I will grow jealous. I will pay you out by talking of our hostess’s many perfections. Do you not think she is beautiful?’ he asked, casting his own longing look in her direction.

‘She seems charming,’ said Elizabeth.

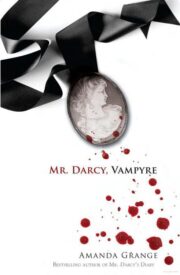

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.