And then she thought of the strange incident when Annie had found her in the gardens and told her that her handkerchiefs had been hemmed. It wasn’t urgent news, it could have waited. But then with a creeping feeling running down her spine, she realised that Annie had not sought her out to tell her about the handkerchiefs; she had sought her out to tell her about the letters, but, on finding that Elizabeth was not alone, she had given nothing but a veiled warning instead.

Then if Annie had known about the letters, had she put them there? If so, where had she found them? And who had stopped them being sent?

Elizabeth remembered Annie’s strange behaviour when she had first noticed the Prince and she wondered if Annie suspected him of stealing the letters. But a moment’s thought showed her that, whatever Annie might or might not have suspected, the Prince could not have been involved because most of the letters had been written before Elizabeth had visited the villa.

But who, then? The only people to touch the letters, apart from herself, were Annie and the footmen who took them to be posted. Annie she could exclude, which left the footmen. But why should any of them do such a thing? They were all loyal to Darcy. They had been in his family’s employ for years. Except…

She remembered an incident in Paris when one of the footmen had fallen ill and had been quickly replaced. He had had excellent references but they had not known anything of the man personally. It seemed ridiculous to think that he was involved, but the fact remained that the letters had not been sent. Could he have been paid to suppress the letters? she wondered. But, if so, why? And by whom?

It might be possible that Annie knew, but Elizabeth could not ask her because… she shivered… because Annie was missing. What had happened to Annie? Where was she? Was she really in the forest with a lover or had something happened to her?

‘Stop the coach!’ called Elizabeth, rapping on the floor of the carriage with her parasol to gain the coachman’s attention. ‘Stop the coach at once!’

But the carriage did not slow its riotous pace.

She wound down the window and called out, ‘Stop! I command you, coachman, stop this instant!’

But his only response was to whip the horses and drive them faster. She felt a rising tide of panic as she realised that she was in the Prince’s carriage, driven by the Prince’s coachman, and surrounded by the Prince’s servants.

She looked out of the window and wondered if she could jump out of the carriage, but it was going too fast. It passed farmers on their way to market and she called out to them as they crossed themselves and stood back to let the carriage pass. Their faces were sullen and hostile, but when they heard her cries, their expressions turned to horror or pity. One woman, moved to action, ran forward when the carriage slowed to take a corner, and thrust a necklace of small white flowers through the window. She said something unintelligible, but her gesture was clear: put it around your neck.

Elizabeth, frightened by her look and by the tears in her eyes, did as she said.

As she did so, she smelt the pungent smell and recognised the flowers as wild garlic.

Strange tales began to come back to her, folk tales she had read in the library at Longbourn, stories of strange creatures that preyed on the living and haunted the forests of Europe, half men, half beasts, mesmeric, and seductive, but evil and dangerous, creatures who bit their victims, piercing their skin and drinking their blood; beasts which could be held at bay by garlic.

‘No, I will not think of it,’ said Elizabeth aloud. ‘It is nothing but a story, a myth, a folk tale. There is no such thing as a vampyre.’

But she held on tight to the necklace, crushing the delicate flowers and leaves with the tightness of her grip.

The coach sped on and she saw that it was heading for the forest. A terrible dread seized her and a fear of the looming trees.

There must be something I can do, she thought.

She looked wildly around the carriage and saw that her travelling writing desk had been packed beneath the opposite seat. As quickly as she could she pulled it open and dipping the quill into the ink she began to write.

My dearest Jane,

My hand is trembling as I write this letter. My nerves are in tatters and I am so altered that I believe you would not recognise me. The past few months have been a nightmarish whirl of strange and disturbing circumstances, and the future…

Jane, I am afraid.

If anything happens to me, remember that I love you and that my spirit will always be with you, though we may never see each other again. The world is a cold and frightening place where nothing is as it seems.

It was all so different a few short months ago. When I awoke on my wedding morning, I thought myself the happiest woman alive… but of what use are such thoughts now? I wanted to spare you but I am in terrible danger. I have nowhere to turn and you, my dearest Jane, are the only person I can trust. I am being abducted by Prince Ficenzi’s servants and I am writing this letter in desperation because I can think of no other way to help myself. I mean to throw it out of the window when it is finished, for I am at this moment in the Prince’s carriage, in the hope that one of the local people will see it. I think they will make sure the letter is sent, for, thank God, I have reason to suppose they will help me if they can.

If this letter reaches you, then please have my father make enquiries about my whereabouts, starting at the Villa Ficenzi near Rome. Tell him he must not be put off, whatever he is told, for the Prince surely knows where I am being taken and he just as surely knows my fate.

When I think of the vast distances that separate us I fear my father will be too late, but he must try and, God willing, my dearest Jane, we may yet see each other again.

There is time for no more, we have almost reached the forest, I must go.

Help me, my dearest!

Elizabeth

She folded the letter and wrote the direction on the outside, then winding down the window she threw the letter out. And not a moment too soon, for the carriage was entering the forest and soon the trees closed about it and there were no more people to be seen. The world became dark and mysterious, with green shadows closing in around the carriage, eerie and malevolent. The sounds were muted and the atmosphere was heavy and thick.

They came at last to a clearing where ferns grew dense and lush, and from above came the faint glimmer of the sky, just enough to show Elizabeth that it was dusk, the nebulous time when worlds collided, night with day, dark with light.

The carriage came to a halt.

Elizabeth, who had been wanting the carriage to stop for miles, was now filled with a terrible sense of dread.

‘Drive on!’ she called in panic. ‘Don’t stop! Drive on!’

But the carriage did not move.

Chapter 13

Elizabeth looked wildly about her and there, in the hazy light in the centre of the clearing, she became aware of a figure, a man, who was standing still and silent. He was dressed in satin, wearing a green coat trimmed with gold lace and green breeches sewn with gold thread. On his head he wore a feathered hat and over his face he was wearing a mask. She had seen that mask before, at the ball in Venice and she had seen it again in her dream. It belonged to the man who had taken control of her and who had propelled her into the past.

She felt a sense of horror overwhelming her. The fear crawled up and down her spine and paralysed her will. She could not move; she could only watch as, with dreadful ceremony, he made her a low bow and then removed his mask.

She knew him now, not the Prince as she had feared, but the Prince’s guest. He had been with her in the library when she had found the book of engravings, when the walls had started to melt.

She stared at him with awe-filled dread. He was terrible in his beauty, his face shining with a dreadful radiance. His features were as smooth as if they had been carved from marble, rigid and full of cold perfection.

He lifted a hand and beckoned her and the door opened of its own accord. Like a dreamer she stepped out of the carriage and crossed the forest floor until she reached him. He took her hand and kissed it in a mockery of a courteous greeting.

Strains of unearthly music began to reach her ears and the forest began to dissolve. The trees were replaced by marble columns and the clearing gave way to a ballroom floor. He took her in his arms and whirled her round in a waltz, and then the ballroom dissolved and they were on the streets of Venice, with revellers laughing and running past them amidst torchlight and gondolas and canals. And then the streets of Venice winked out and they were in the forest again, just the two of them, with the carriage and the servants vanished.

‘Please allow me to introduce myself,’ he said, bowing low over her hand. ‘It is an honour to meet you, Mrs Darcy. But what is this? You do not return my greeting.’

‘I do not know your name,’ she said, finding that her mouth, at least, was her own.

‘Then I must tell it to you. I am called many things by many people, but you may call me husband.’

‘I already have a husband,’ she replied.

He gave an unnatural smile.

‘You have nothing. You have a man who is afraid to touch you. He has married you but he has not bedded you. He is no husband to you.’

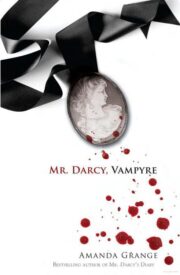

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.