‘Happy?’ asked Darcy.

‘Yes, very,’ said Lizzy, taking his arm.

‘I thought, when we were in Venice, that you might want to go home.’

‘Perhaps I did, but I feel differently now. I don’t suppose we will ever come so far again so let us make the most of it whilst we are here.’

As one of the footmen walked past she attempted to put her glass, now empty, on his tray, but he turned away at the last moment and the glass fell to the ground where it broke into pieces.

Elizabeth gave an exclamation of annoyance and bent down to pick up the glass before one of the other guests should tread on it, but Darcy, bending down beside her with preternatural speed, said urgently, ‘Don’t!’

He caught her hand and jerked it back, but the action pulled her fingers over the jagged edge and a spurt of blood gushed from the wound in a fountain of brilliant scarlet. She felt a terrible energy in him, and he began to tremble.

‘Go inside at once!’ he said, standing up and backing away from her. ‘Have your maid bind your wound. Now!’

‘It’s nothing,’ she said, perplexed, as she stood up. ‘Only give me your handkerchief, that is all I need.’

‘Come,’ said Lady Bartholomew, who had seen the accident and who had approached to help. ‘Your husband is right. In this hot climate any wound, no matter how small, can soon go bad.’ In a lower voice she said to Elizabeth, ‘It often happens this way, many gentleman cannot stand the sight of blood. They are often very squeamish. Humour your husband in this. He will not want to appear weak in front of the other guests.’

Elizabeth allowed Lady Bartholomew to lead her away, but as she went into the villa she felt a sense of alarm and profound unease, for the look on Darcy’s face had not been squeamish. It had been ravenous.

Chapter 11

My dearest Jane,

We are now in the south of Italy, near Rome, and the weather is so warm that today I did not even need to wear my shawl when I went outside. You, I suppose, are wrapped up in your pelisse and cloak! The days here are long and move at a leisurely pace. There are impromptu balls almost every evening, and if we are not dancing, then we are playing at cards or backgammon, and if not that, then we play the piano and sing. In the daytime we walk in the gardens. I am just about to go outside and play at croquet. I am becoming quite a proficient!

My dear Darcy remains an enigma. Sometimes when he looks at me I feel a sense of expectation, but sometimes I am filled with an unaccountable unease. I am longing to talk to you again, and yet I am not longing to return home. I have not yet had my fill of Italy. And so, for the moment, adieu.

The game of croquet was about to begin when Elizabeth joined the rest of her party on the lawns behind the villa. Sir Edward and Lady Bartholomew were there, as well as Monsieur Repar, Mrs Prestin, and Darcy. Darcy looked up as she joined them, and there was something hungry in his look.

‘There you are, Mrs Darcy! You are just in time to start us off,’ said Sir Edward jovially.

Elizabeth took her shot, knocking the ball cleanly through the hoop, and she was then succeeded by Lady Bartholomew and Mrs Prestin. The gentlemen praised their efforts then took their own turns. There was a friendly rivalry between Sir Edward and Monsieur Repar, and Monsieur Repar smiled broadly when Sir Edward struck the ball poorly, only to be repaid when his own shot went wide and Sir Edward laughed in a friendly fashion.

Darcy played well, but it was Lady Bartholomew who excelled. Every shot she made was clean and the ball went wherever it was meant to go, not too far but just far enough. It sailed through hoops and rolled smoothly across the grass.

She was just about to take her final shot, which would win her the game, when clouds appeared suddenly in the sky and a storm blew up from nowhere. The light dimmed and turned purple, changing the single cloud from a bright puff of gossamer into a dark and swollen mass that throbbed like a livid bruise.

‘Poor fellow, he isn’t seeing the place at its best,’ said Sir Edward as a coach rolled up the drive and disgorged a new visitor. ‘He can hardly see it in this light.’

Lady Bartholomew took her last shot and won the game just in time as a strong wind whipped the ladies’ dresses round their ankles and the rain suddenly threw itself from the sky. They all ran inside, being soaked by the time they reached the sanctuary of the hall. The group dispersed, the gentlemen arranging to meet again once dry and play a game of billiards whilst the ladies announced their intention of writing letters or otherwise occupying themselves in their own rooms.

Elizabeth, once she had changed out of her wet clothes, retired to the library, where she hoped she might find something in English she could read in order to pass the time before dinner. The library was an impressive room, and one she had discovered soon after arriving at the villa. It was very large, with high ceilings, and it was lined with books. But today, despite the tall windows, she found it hard to see, for outside it was almost as dark as night, almost dark enough for her to need a candle. Thinking she would rather not light a candle so early in the day, no matter how dark it was, she persevered without one.

The books were bound in leather with the most exquisite tooling on the covers. Gold lettering spelled out the titles and the authors’ names, which were written in flourishing scripts. She thought of the library at Longbourn, with its well-worn books, and she thought how much her father would love the Prince’s collection.

As she wandered round the room she tilted her head to one side, the better to read the titles, although most of them were in Italian and barely comprehensible to her. But here and there she recognised a few English books: Tom Jones, Robinson Crusoe, Shakespeare’s plays.

She found herself curiously drawn to one corner, where the books were more densely packed than elsewhere, and one book in particular seemed to call to her.

She took it out and looked at it. It was bound in old, deep red leather and it was ornamented with script in gold lettering, which had been handled so often that it was beginning to flake. She could still see the title, however, Civitates Orbis Terrarum.

Opening the book, she saw that it had been published in 1572 in Cologne and that it was a book of engravings. It contained maps and prospects and birds’ eye views of various cities around the world. There were people in the engravings too, dressed in sixteenth century costume, the women wearing long dresses which flowed into trains behind them and the men wearing short cloaks.

It was fascinating to see views of various cities in times gone by, and as she turned the pages she found herself looking at images of places she recognised. She knew at once when she had arrived at engravings of Venice. There was a view of San Marco and the Palazzo Ducale, and—she felt a creeping fear crawl over her—the Palazzo Ducale was on fire. She had seen it before, that fire, in her dream. It had frightened her, and it frightened her again, so badly that she tried to thrust the book away from her, but somehow the book seemed to be stuck to her fingers and she felt compelled to look at the image.

I must have seen it before, she thought. I must have seen this engraving somewhere and that is why I saw it in my dream. It must have been a memory.

But she knew she had not seen the book before, and that, even if she had, it could not be the source of the image in her dream: the view in the Civitates was looking at the burning palace from the direction of the canal, but in her dream she had seen it from the other direction.

I didn’t dream it, she thought, with a terrifying realisation. I was in the past. I was there.

She dropped the book, letting it fall from numb fingers. Despite its great antiquity and obvious value, she felt only the vaguest sense of relief when it was caught by other hands which stopped it plummeting to the floor, for one of the Prince’s guests had entered the room and had saved it from its fall.

‘My dear young lady,’ he said in concern, ‘you are as white as a ghost. Are you unwell?’

She turned towards him and had difficulty in making out his face. It seemed ageless: unlined and yet old, sympathetic and yet devilish. It floated before her in silent mockery, completely at odds with his words and behaviour, and she felt very strange.

‘Here,’ he said, offering her his arm.

She did not respond, only looking at him, and he pulled her hand through his arm himself, saying, ‘Let me escort you to a seat.’

As he touched her, she felt her will altering, flowing, and merging with his. She moved with him to one of the window seats. She was ensorcelled by him. Her body was light and ethereal and her thoughts were unclear, as though her mind was filled with mist.

She was aware of a peculiar sensation as the room around her began to alter, distorting and changing like a wet portrait in the rain. The green wallpaper began to melt and run down the walls and a deep ochre ran down in great rivulets behind it and took its place. The curtains too began to change, their dark green velvet dropping away to be washed over with rivers of gold silk. Pictures were appearing and mirrors disappearing; beneath them the console tables were altering, their legs narrowing and their tops flowing with marble; the vases of flowers were being replaced with porcelain and ormolu clocks. The carpet was giving way to polished floorboards and the sound of unearthly laughter filled the air. He seized her in his arms and waltzed with her around the room, whispering to her in some unintelligible language.

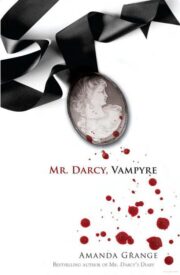

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.