‘I didn’t. I thought it was just in the dream. Did it really burn?’

‘Yes, it did, a long time ago. Centuries ago.’

‘Then someone must have told me about it, or perhaps I read about it somewhere.’

‘Yes, perhaps,’ he said, but his mood was sombre.

‘It was nothing, my love,’ she said, and now she was comforting him. ‘A nightmare, that is all.’

‘Of course,’ he said with a distant smile.

But he put his arms around her and he did not let her go.

Chapter 10

The next morning saw a change in the weather. The last of the summer sunshine had disappeared, to be replaced by a misty, eerie fog. When Elizabeth stepped onto her balcony, she saw not the glorious blue sky and the glowing colours of late summer, but the white and ghostly miasma of autumn, which wrapped itself around the palaces and bridges like a choking vine. Gondolas loomed out of the mist like wraiths, appearing and disappearing beneath her with a sepulchral air, and the dolorous tolling of the Campanile’s bell seemed to come from a vast distance.

Elizabeth and Darcy were both subdued at breakfast. They ate, not in the courtyard as they had done when the weather was sunny, but in the dining room, an imposing, formal room ornamented with classical frescoes. Darcy ate little and left as soon as he had finished, saying that he had an appointment with his boot maker. At any other time, Elizabeth would have shown an interest, but she was thinking of her arrangement to meet Sophia at the Venezia Trionfante with some misgiving. It had been made on the previous evening, so that they would have an opportunity to talk over the ball, but she had no desire to go out into the fog. She consoled herself with the thought that it might clear by the time she needed to leave, but when the appointed hour came, it was as heavy as ever.

With great reluctance she donned her cloak, her bonnet, and her gloves, and she left the palazzo with Annie beside her. The courtyard seemed sad and cheerless without the sun to brighten its stones, and she noticed for the first time that the steps were crumbling and that there was green slime on the landing stage. She hesitated under the colonnade, thinking that the gondola was missing, and only realising that it was tied up in its usual place when the gondolier spoke to her. She took his hand and was glad of his assistance. It no longer seemed such an easy thing to climb into the flimsy little craft, now that the landing stage was slippery with moisture and the gondola itself was obscured by the fog, and she sat down and reclined with relief, only to sit up straight again because the cushions were damp and clammy. She looked at Annie and the two women pulled faces, then wrapped their cloaks more tightly around themselves, and peered ahead through the fog.

‘Where do you go to, Signora?’ asked the gondolier.

‘To the Venezia Trionfante,’ she said.

‘The Venezia Trionfante?’ he asked with a frown. ‘I do not know this place.’

There came a cry through the mist as another gondolier shouted a warning and a few seconds later another boat appeared.

‘Ayee! Carlo! Where is the Venezia Trionfante?’ cried her boatman.

He spoke in Italian, but Elizabeth was pleased to find that she could understand him.

‘The Venezia…? I know of no such place,’ said the other gondolier, resting on his oar and thinking.

‘It is a café,’ said Elizabeth.

‘A café!’ called out her boatman.

‘There is no such café in Ven—ah! you mean Florian’s! It has not been called the Venezia Trionfante for many, many years, not since it was first opened, I think, and that is eighty years ago! These English, they are crazy, they know nothing!’

‘Ah! Si! Florian’s! I know where it is! In the square of San Marco!’ cried Elizabeth’s boatman, thanking him, and straight away he was plying his oar, sending the gondola through the swirling mist and into the hidden waters beyond.

Buildings loomed up in front of them every time the mist parted for a few seconds, but instead of seeing the warm colours and the splendid proportions, Elizabeth saw the crumbling corners and the exposed brickwork where the plaster was falling off. The gilding was chipped and looked tawdry in the dull light. The water too seemed darker and dirtier, full of murky secrets.

The fog had still not lifted by the time she arrived at St Mark’s square. The great basilica was hidden and so was the towering Campanile. She could not see Florian’s anywhere, but she found it at last by walking all around the square, her head down and her cloak pulled firmly round her with its hood up, covering her head and face.

She went in, glad of Annie’s company, for the people looked at her with hostility and she felt awkward and out of place. When she discovered that Sophia was not there she felt even worse and she stood by the door for a moment, deciding what to do. The customers were still looking at her, some appraisingly, some suspiciously, and the waiters surveyed her with stony faces. She wished there were some women there, for Sophia had said that women were admitted to the café, but there were none at the tables; they were all men.

‘We will wait a little,’ said Elizabeth to Annie, taking a seat at an out of the way table. ‘I am sure Sophia will be here presently. I think we are perhaps rather early.’

The waiter came and Elizabeth ordered coffee.

In England she would have enjoyed looking at the people who sat and talked or watching the world go by, but some of those in the café carried with them an air of danger, and she looked down, not wanting to meet their eyes. She looked instead at her coffee, stirring it with its silver spoon. It was with relief that she heard Sophia arrive at last. Looking up, she saw Sophia being greeted warmly by the waiters and many of the customers, and the café, at once took on a more cheerful air.

‘Ah, Elizabeth, I am sorry I have kept you waiting, I was delayed,’ Sophia said. ‘Maria and I, we have been to the see the sick and the dying, to give them succour, and we were delayed on our return by the fog. Nothing is moving quickly in Venice this morning, not the people in the streets nor the gondolas in the canals; it is all travelling warily, hesitantly, and with good reason, for a misstep can lead to disaster in such weather, with the city so full of canals. It is the change of season. In summer we have the sun and this year it has lasted long, but now, today, it is autumn and the mists they have come down like a shroud.’

‘Is it often foggy here?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘But yes, and in the winter it is worse; we have snow. The cold winds, they blow down from the mountains, and the canals, they freeze. But never mind, we are in the Trionfante, what care we for fog or ice or snow? You did not have any trouble finding it, I hope?’

‘To begin with, yes. My gondolier had to ask where the Trionfante was. He couldn’t find it until we realised it was called Florian’s now,’ said Elizabeth.

Sophia paused.

‘Ah, yes,’ she said. ‘Florian’s. Of course. He was the patron many years ago, and the café became known by his name, I had forgotten. It is a wonderful place, is it not?’

‘Ye—es,’ said Elizabeth.

‘You do not like it? But ah, I see it in your eyes, you are afraid of some of the people. They whisper in the corners do they not?’

‘Yes. They look like they are plotting,’ said Elizabeth, with a smile to show that she knew such a thought was ridiculous.

But Sophia treated her remarks seriously.

‘Yes, they are plotting. They want to put an end to the French; they want Venice to return to what she once was. But how can we return to what has gone?’ she asked sombrely.

Elizabeth had the feeling that she was speaking of something more personal than the fate of Venice and did not interrupt her thoughts by a reply; indeed, she was sure that Sophia wanted none.

‘The glory, it has passed,’ Sophia went on, looking round the room. ‘The great days, they have gone. There is no place in the world now for our kind,’ she said, turning suddenly to look at Elizabeth. ‘Not unless we will take it, and take it with much blood. There are those who will do so, but me, I find I love my fellow man too much and I cannot end his life, not even to restore what has been lost. But without great ruthlessness, glory fades and strength is gone.’

Elizabeth’s mood, already low, became lower still. There was a darkness lurking beneath the gilding of the city and Venice had lost its appeal. She did not quite know how or when it had happened, but now, instead of beauty, she saw only decay. Sophia’s face, so bright the day before, now seemed tired, and her conversation now seemed more macabre.

Seeming to sense something of Elizabeth’s drooping spirits, Sophia made an effort to lighten the conversation and she began to talk about the ball.

‘You were a great success last night. “The English bride” was spoken of everywhere. We Italians, we have a passion for romance, and your marriage to Darcy is just the sort of thing we like: two people separated by a great gulf coming together with love triumphing over all. It is a thing that does not often happen, and when it does we celebrate it, no matter how hard the future might be. Your dress, it was remarked upon, and how well it suited you, and how surprised everyone was when you removed your mask.’

Elizabeth did her best to respond but could not recapture her enthusiasm for either Venice or the ball, and she was glad when both she and Sophia finished their coffee so that they could say goodbye. She set out again with Annie, returning to the Darcy palazzo in no better spirits than she had left it.

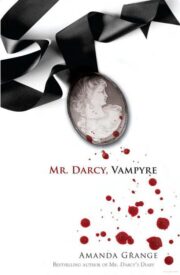

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.