Elizabeth laughed. Sometimes it seemed as though her Aunt Gardiner had hundreds of children, when they were all running around noisily on a summer’s afternoon!

‘Do any of you have sisters?’ Elizabeth asked, as they gathered on the rug and began to eat.

‘I have two,’ said Clothilde, between mouthfuls of game pie, ‘both older than me. I am the baby of the family.’

‘Do they live nearby?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘No, my family is scattered,’ she said. ‘Some of them live in France, some in Austria, and some even further away.’

‘So that is why you thought that Charlotte had settled an easy distance from her family,’ said Elizabeth to Darcy. ‘And when compared with settling in another country, then yes, she has.’

‘Everything, it is relative,’ said Frederique as he helped himself to a glass of wine, and then helped Elizabeth to one as well.

‘But what are you doing here?’ said Isabella to Darcy. ‘I hope you are thinking of living amongst us again?’

‘No,’ said Darcy. ‘The Count thinks he might have found a tenant for me.’

‘Vraiment? Who?’

They were all eager to know, and when Darcy mentioned the name they each had their own opinion to give.

‘He will not like it. He thinks he wants to live in the country, but he would never be happy away from town,’ said Louis.

‘He will come here for a few months and then he will go,’ agreed Carlotta.

‘Is he married?’ asked Elizabeth. ‘When an unmarried gentleman moved into Meryton it was the talk of the neighbourhood, and he was seen as the property of one or other of the Hertfordshire daughters! I am sorry if I offend you, but it was so!’

Isabella sat up straight and looked at Louis with interest.

‘Well? Is he handsome?’ she asked.

‘He is not handsome enough for you!’ said Louis with a laugh.

‘And how do you know what is handsome enough for me?’ she asked. ‘I might like him very well.’

‘You might, I suppose. Very well, he is unmarried.’

‘Louis!’ said Frederique with a groan. ‘You are a traitor! Why not tell them that yes, he is married, and then he can know some peace when he arrives.’

‘I think he would like very much the company of such beautiful young women; it will amuse him to have them all paying a call on him as soon as he arrives.’

‘But what is this you say?’ asked Isabella. ‘When we pay a call? It is our fathers who will call. Carlotta’s father cannot call, it is true, but my Papa shall go for both of us.’

They continued to laugh and banter and tease each other throughout the meal, the women asking more questions about the prospective tenant and the men laughing at them whilst serving Elizabeth with all the choicest delicacies from the hamper. They were attentive and gallant, and Elizabeth responded in a lively fashion.

When they had finished eating, the ladies packed the remains of the picnic away in the hampers and the gentlemen carried them outside and put them on the roof of the carriage. The rug was folded, leaving a clean space where it had swept away the dust, and the windows were closed. The door was locked and then they went outside, those with horses mounting them in a flurry of skirts and boots, all except Carlotta who professed herself tired. Darcy offered her his place and handed her, together with Elizabeth, into the carriage.

The road back was full of pleasantries, and Elizabeth and Carlotta were not forgotten. Louis and Frederique rode beside the carriage, laughing and talking with them through the open window.

The castle at last loomed into sight. Against the backdrop of the late afternoon sunlight it looked less gloomy than heretofore, but once across the drawbridge, Elizabeth felt some of her apprehension return. The mercenaries were still patrolling the courtyard with their leashed hounds, and even the sight of Frederique and Gustav dismounting and talking to them did not make the sight any less threatening. Those with horses took them round to the stables, eager to make sure that the grooms rubbed them down thoroughly, and Elizabeth went back into the castle. She went upstairs to repair the damage to her hair, wrought by the elements, and to remove her outdoor apparel.

When she had gone halfway up the imposing stone staircase, Elizabeth heard Darcy calling her. She stopped and turned round. He was standing at the bottom of the stairs looking up at her.

‘Elizabeth!’ he said again, as he began to climb the stairs towards her place on the half landing.

Illuminated by the light from the large window she made a lovely sight. Her cheeks were aglow, her eyes sparkled, and she radiated good humour and health.

‘I am glad you enjoyed the company of my uncle’s guests, but it would be well not to encourage them too far,’ he said in some agitation.

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ she said in surprise.

‘You were enjoying their attentions,’ he said with a sudden spurt of jealousy.

She was taken aback by the injustice of his remark and flashed back, ‘And why should I not? I never get yours.’

He looked startled.

‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

‘You know full well what I mean. We have been married for weeks and yet I am still not your wife.’

‘Elizabeth—’ he said, and then stopped, as if at a loss.

‘Why do you never come to me?’ she asked him, hurt.

‘I—’ He shook his head. ‘I should never have brought you here,’ he said.

‘Then why did you?’ she asked.

‘I didn’t know how it would be. I thought it would be different.’

‘Different? How?’

‘Not so difficult—or yes, difficult, but difficult in different ways.’

‘I don’t see what is so difficult,’ she said, looking at him beseechingly and reaching out a hand to touch him.

‘No, I know you don’t,’ he said, but he did not take her hand.

‘Then explain it to me. Talk to me, Darcy,’ she begged him, taking his hands and looking into his eyes. ‘Tell me what is wrong. I will not leave this spot until you talk to me, though sunset is already on its way. I will stand here until dark if necessary.’

He lifted his eyes but he did not look at her, he looked beyond her, over her shoulder, to the reddening sky. Then his whole attitude changed.

‘That’s no sunset,’ he said.

She was startled and, looking over her shoulder, she saw that he was right. The sky was not flamed with crimson, it was stained with a fire’s glow.

A bell on the stables started to ring out and there was a clamour from the courtyard outside. Through the window she saw the mercenaries mount with all speed as the grating of the drawbridge’s chains rent the air. The vast bridge began to lower and the mercenaries streamed across it, filling the air with the flash of their bright swords.

‘There is no time to lose,’ said Darcy, seizing Elizabeth by the hand and pulling her down the stairs, just as the Count appeared at their foot.

‘Quickly,’ the Count said, ‘you must go at once. The mob, it is on the move.’

Elizabeth was at once alarmed, remembering everything she had heard about the revolution in France, when the mobs had stormed the houses of the nobility and wreaked havoc, burning and murdering as they went.

‘We can’t leave the castle,’ she said. ‘The walls are thick. We will be safe here.’

‘We can and we must leave,’ said Darcy.

The Count said something under his breath and Elizabeth thought he said, Get her away from here. It is her they will not stand for, before realising that she must be mistaken, because those words didn’t make sense. Then, in a louder voice, he said, ‘Do not stop for your things. Me, I will have them sent on.’

‘We can’t leave at night,’ said Elizabeth. ‘The horses—’

‘We cannot ride our own horses, there is no time to have them readied,’ said Darcy.

‘You will find everything needful at the usual place,’ said the Count to Darcy. ‘Go quickly, my friend, and the wind, may he be at your back.’

Darcy nodded, then saying, ‘Send our things on,’ he turned to Elizabeth and said, ‘We must go.’

Caught up in the sense of urgency, she ran down the flight of stairs with Darcy beside her, but when she headed for the door he caught her hand and, pulling her along with him, took her to another staircase leading down into the bowels of the castle. The steps were smooth and slippery, and the cold bit into Elizabeth’s feet through the soles of her shoes. The light faded as the windows receded and they were running in near darkness, until at last Darcy pulled her through a studded door. There he took a torch from a sconce on the wall and fumbled on a shelf, striking a light with a tinder box. The torch caught fire and a light shone out, a dreadful echo of the torches of the mob.

They were in a storeroom with sacks of flour stacked against the walls. It was hewn out of the rock on which the castle stood, and the ceiling was so low that Darcy had to stoop and Elizabeth was in danger of hitting her head.

Darcy pulled aside the heavy sacks of floor and then, taking the torch in one hand and Elizabeth’s hand in the other, he led her on through the door that had been revealed. Elizabeth found herself in a dark, dank tunnel with water running down the walls, and she shuddered with cold and fear. The floor was uneven, and twice she stumbled, but she quickly righted herself, wondering where they were going. She guessed they were passing beneath the castle walls and the thought of so much weight above oppressed her so that she hurried her pace. At last they came to another thick door which was barred with a stout oak log. Darcy again handed her the torch and then heaved the bar out of its housings and opened the door. Beyond was a tangled thicket of thorns and ivy, disguising the opening, and beyond that lay the forest.

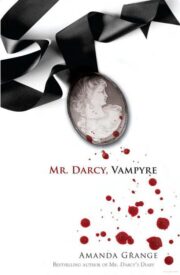

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.