As the coach rolled out of the gate, Elizabeth found herself glad to be leaving the castle, even for a short time. She was not looking forward to the journey through the forest, but to her surprise, she found that it had taken on a different aspect in the daylight. Gone were the dark and gloomy shadows and in their place were dancing sunbeams and sunlit clearings. The undergrowth was full of nature’s bounty, with nuts and berries growing profusely, and here and there she could see patches of mushrooms, too.

‘When we were children, Jane and I used to take a basket and go out blackberrying,’ said Elizabeth. ‘We would set out early in the morning and Hill would give us whatever she could spare from the larder, a piece of chicken pie, perhaps, with an apple and a slice of cake. We would go out into the fields and woods round about Longbourn, and we would spend the day filling the basket. We would at last return home, laden down with fruit, tired but happy. Kitty and Lydia would dance around us and Mary would look up from her pianoforte and her eyes would gleam. Mama would scold us for dirtying our dresses—or at least she would scold me, for Jane never ruined her clothes—and Papa would smile at us and say we had done well. Having shown off our spoils to the rest of the family, we would take the basket to the kitchen. Hill would say that it was the finest crop she had ever seen and she would bake a pie for tea. I well remember the taste of that first blackberry pie of the season; it always tasted better than any other.’

Darcy smiled and said, ‘I used to pick fruit in these very forests. I always felt free out here in the wilds. At Pemberley I was conscious of being the master and I had to set an example to those around me. Here I could be myself. I would wander through the forests from morning to night and not go home until dark.’

‘Were you not afraid of the wolves, or did you have outriders to watch over you even then?’

‘No, I didn’t have outriders, and no, I wasn’t afraid. I knew how to protect myself.’

She thought of the education of an English gentleman and knew that he would have learned to handle a sword and pistols, just as she had learnt to sew and paint. She imagined him walking through the forest self-reliant and unafraid.

‘Were your parents happy for you to wander?’

‘Yes, they were,’ he said. ‘They never prevented me from doing anything I wanted to do, and besides, they thought it was good for me to be out of doors.’

‘Did you used to stay at the hunting lodge, or did you stay with the Count at the castle?’

‘To begin with I stayed with the Count, but later I stayed in the hunting lodge.’

‘Do you have many hunting lodges?’ she asked.

‘Five. There used to be seven but two of them were in such a poor state of repair that I disposed of them some time ago. I seldom travel to Europe now; my time is tied up with Pemberley.’

‘The Pemberley estate is even bigger than I imagined and it stretches farther than I ever realised,’ said Elizabeth as she reflected, not for the first time, that she had moved into a very different sphere of life. ‘I knew about the house in London and Pemberley, of course, but not of anything in Europe.’

‘There used to be a town house in Paris but it was destroyed in the revolution. When the storm has finally spent itself, I intend to rebuild the house, or perhaps buy another house there.’

‘Do you think the wars with France will ever come to an end?’

He nodded.

‘Everything does eventually, and I hope it will be sooner rather than later,’ he said. ‘There are other properties in Europe, too, and there are smaller properties scattered throughout England, all of which I hope to show you in time.’

Elizabeth thought of how her mother’s eyes would widen at the thought of properties in Europe, as well as properties scattered throughout England. She could almost hear her mother telling Lady Lucas and Mrs Long all about it!

The coach followed the road through the trees until at last it came to a high wall running alongside the road. A little further on there was an iron gate, and through its bars Elizabeth could see a box-shaped house as high as it was wide. One of the footmen jumped down to open the gate, which creaked as it swung open, and then the coach bowled through. It went up an unkempt drive, full of encroaching weeds and tough grasses, which lay in the midst of overgrown grounds, and came to rest outside the lodge.

Although it was called a lodge, it was larger than many of the houses in Meryton, with three storeys and large chimneys. It seemed, at first sight at least, to be in a good state of repair. The steps leading up to the front door were sound, and the rooms, though smelling somewhat stale, were dry and in good condition. The floorboards felt firm as she walked over them and the window shutters were unrotted. There was no furniture and no decorations, save for the cobwebs that were strung from every corner and were hanging in festoons from every shelf or ledge. She went over to the windows and threw them wide, letting in the fresh air.

‘This is better than I had expected,’ said Darcy, as they wandered through the rooms, throwing windows open as they went. ‘It needs cleaning and the grounds need some attention, it needs furniture, too, but other than that I see no reason why it should not be let.’

Elizabeth thought of another letting, in another neighbourhood, just over a year ago, and remembered the excitement it had brought in its wake. Her mother had thought of nothing else for weeks! She wondered if there were any similar families in the mountains who might be as delirious at the thought of a new tenant at the lodge as her mother had been at the thought of a new tenant at Netherfield Park. She imagined them dressing in their finest and going—where? Not to the assembly rooms, for there were none nearby. To a private ball, perhaps.

When they had inspected the lodge from top to bottom Darcy, having seen what he wanted to see, suggested they return to the castle. They were just about to leave the lodge when they heard a commotion outside. Elizabeth’s first thought was that it was bandits, but the shouts quickly resolved themselves into friendly halloos and the sound of galloping hooves came to a halt just outside the drawing room window. Looking out, she saw some of the Count’s guests leaping from their saddles and, breathless and excited, heading towards the house.

They were dressed in simple woollen clothes, suitable for hard riding through the countryside, the women wearing serviceable riding habits and the men wearing rough coats and breeches with well-worn boots. They disappeared from view and then there was the sound of the front door being flung open and Gustav’s voice called, ‘The Count, he told us you were visiting the hunting lodge and so we thought you might like some company. We have brought a picnic.’

The room was suddenly full of people, their faces flushed with exercise, all laughing and talking at once.

‘What a morning we have had of it!’ said Gustav. ‘The best sort in many a long day. There is nothing to beat a bright autumn morning when the air is crisp and the blood is flowing with the thrill of the chase. We must persuade you to hunt with us tomorrow, Darcy, and Elizabeth, too.’

‘Elizabeth does not hunt,’ said Darcy sharply.

‘Then you must teach her. There is nothing like hunting for sharpening the senses and bringing them to life. Every sight, scent, and sound is magnified. To live without hunting is to be only half alive. Well, Elizabeth, what is it to be? Will you hunt with us tomorrow?’ asked Isabella.

‘No, I thank you, not I,’ said Elizabeth.

‘A pity. But perhaps we may persuade you yet,’ said Louis.

Carlotta, meanwhile, had unpacked the hamper, spreading the contents out on a rug in the window seat. There was cold chicken and ham, breads and cheeses, game birds and venison, and to go with the food, there were bottles of wine.

‘We have you to thank for this, Elizabeth,’ said Gustav as the plates were passed round. ‘Polidori has not invited us to the castle for years. I had forgotten how much fun it was to hunt hereabouts.’

‘You have not forgotten our agreement, I hope, and been killing things you shouldn’t,’ said Darcy.

‘Never fear, we have respected the Count’s property and your wishes. We hunt to live, not to make enemies of our neighbours.’

‘You must come here more often,’ said Frederique, lifting a leg of chicken to his mouth.

‘Yes, indeed, and bring your friends and family with you. Do you have any sisters as beautiful as yourself?’

‘Yes,’ said Elizabeth.

‘No,’ said Darcy at the same time.

‘I have four sisters,’ said Elizabeth.

‘But none of them as beautiful as yourself,’ said Darcy.

‘Naturally. How is it possible to match perfection?’ asked Louis with roguish gallantry. ‘But if they are not all as beautiful, they are at least numerous. Four sisters is a family indeed.’

‘Two of them are married,’ said Elizabeth.

‘Which means that two of them are not. I will have to visit England again with all rapidity.’

‘And you, do you have brothers and sisters?’ she asked him.

‘Me, I have two brothers, but they are neither of them as handsome as me!’ he said outrageously.

Frederique laughed.

‘His brothers are the most handsome men you have ever seen. They quite put him—how do you say it?—in the shade!’

‘Are they married?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘Mais oui. Both of them have been married for many years.’

‘Do you have any nephews and nieces?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘More than I can count. Hundreds of them!’ he said.

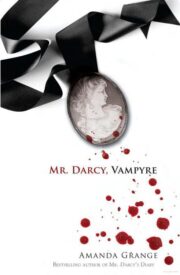

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.