‘Tell me, how are the sleeves this year? Are they long or short?’ asked Clothilde.

‘They are scarcely there at all,’ said Elizabeth. ‘They are nothing but frills at the top of the arm.’

‘That is all very well for a heated drawing room where the press of bodies makes one hot, but it will not do for the mountains where we have snow for half the year,’ said Isabella, laughing.

‘It might, if we sit close to the fire,’ said Clothilde. ‘I like the thought of sleeves that are nothing more than a frill.’

‘Do you really want to sit close to the fire all day?’ Isabella teased her. ‘No, you cannot sit still for more than a few minutes at a time. You would be jumping up and going somewhere, doing something.’

‘Not all the time; in the evening now and then sitting still would not be so bad if it meant I could be comme à la mode. And how are the skirts, are they all like your dress, with the waist very high?’

‘Yes,’ said Elizabeth. ‘They have been this way for some time.’

‘We have much to catch up with,’ said Carlotta. ‘We used to get the fashion journals, but since the troubles, they have not been so easy to come by.’

‘Then we must go to Paris,’ said Clothilde. ‘We must treat ourselves. Too long have we been content to live in the forests. We will take a trip to the capital and return laden with gowns and shawls and gloves and fans. We will startle our men folk with our fashionable dress and perhaps it will prompt them to go to town themselves and get some new clothes, too. I am sure they could benefit from them. They look very clumsy, our friends, next to Mr Darcy.’

‘I cannot believe Frederique will wear new clothes; his old ones are too comfortable,’ said Clothilde. ‘He will wear them until they fall from his back! Have you men like this in England, Elizabeth?’

‘We have men of all kinds,’ she said, ‘some who follow the fashions closely and some who dress as they please.’

‘Ah! Then it is the same everywhere, I think! But here they are now. We were just saying how we would like to go to Paris and buy some new clothes, and that you should come too,’ she said, as the men entered the room.

‘New clothes!’ said Louis in horror. ‘I cannot abide them. Always they are uncomfortable. They scratch or they are too tight or they are too loose, and they are never the right shape. A coat needs to be worn for a year before it is comfortable.’

‘You see, Elizabeth, we can do nothing with them!’ said Carlotta with a laugh.

A game of cards was suggested and everyone readily agreed to the plan. They were just taking their places at the card table when there came a sudden loud knocking on the front door.

Elizabeth looked up in surprise and all eyes turned towards the hall.

‘Now who can that be?’ asked the Count.

There was the sound of voices in the hall. The butler’s voice was angry and contemptuous, and the other, a woman’s voice, was feeble with age and yet at the same time resolute. A moment later the door was flung open and the old woman entered, followed by the outraged butler, who said something in his own language to the Count. Although Elizabeth could not understand his words, his indignation was clear, as was his step towards the old woman. But the Count lifted his hand and the butler stepped back, muttering.

‘We have before us an old crone who asks to tell our fortunes. What say you?’ said the Count.

‘Let her in!’ said Frederique, laying down his hand of cards. ‘It would be a thousand pities to miss such sport.’

‘What do the ladies say? Would it amuse them?’ asked the Count.

‘Certainly,’ said Clothilde.

‘But assuredly! I would like to discover what she makes of my hand,’ said Isabella with an impish smile.

The Count, his eyes glittering in the candlelight, turned to Elizabeth. ‘Do you object, Mrs Darcy?’

The old woman came forward. By the light of the fire Elizabeth could see that she was not as old as she had at first appeared. Her face was lined but not wrinkled, and her stoop was assumed. Elizabeth guessed that the woman was a friend of the Count’s, someone who had agreed to pose as a fortune-teller in order to amuse his friends, and she said, ‘No, I don’t object at all.’

‘Alors, then please, come closer to the fire,’ said the fortune-teller.

She spoke with a heavy accent, but she spoke in English, confirming Elizabeth’s opinion that she was a friend of the Count’s and not the peasant woman she appeared to be.

She established herself on a stool by its side, protected from the brightness of the candles by the shadow of the mantelpiece.

Clothilde stepped forward, but the old woman said, ‘Not yet, my dark lady. There is one here who must come before you; I see a bride.’ She fixed her eyes on Elizabeth. ‘I would give a fortune to the bride.’

Elizabeth went over to the woman and sat opposite her and the woman held out her hand.

‘You must cross my palm with silver,’ she said.

‘Ah! Now we come to it,’ said Frederique, laughing. ‘The fortune is nothing, the silver is all.’

There was a murmur of laughter amongst the Count’s guests and then Darcy stepped forward, placing a coin in the old woman’s hand.

The fortune-teller nodded, bit it, and then slipped the coin into the folds of her cloak.

‘Now, come close, ma belle.’ She took Elizabeth’s hand and turned it over so that it was palm upwards. ‘I see a young hand, the hand of a woman at the start of her journey. See,’ she said, pointing to lines that ran across it, ‘here are the dangers and difficulties you will face. Your hand, it is the map of your life and the lines, they are the dangers running through it. They are many, and they are deep and perilous. You will be sorely tried in body and spirit, and you must be careful if you are to emerge unscathed.’

‘That all sounds very exciting!’ said Gustav.

‘And very general,’ said Clothilde with a laugh.

She had drawn closer and was now standing by the fire.

‘You think so?’ asked the fortune-teller sharply. ‘Then give me your hand.’

Before Clothilde could react, the fortune-teller seized her hand and turned it palm upwards. She ran her finger across its lines and then let out a moan and began to rock herself.

‘Darkness!’ she wailed. ‘Aaargh! Aaargh! The emptiness! The void! Everything is darkness!’

‘She puts on a fine show,’ said Frederique in a stage whisper.

‘I put on no show,’ said the woman, turning to him sharply. ‘Never have I felt such emptiness, such terror and such darkness. The cold, it terrifies me. It turns my bones to ice. But you, ma belle,’ she said, giving her attention once more to Elizabeth and looking at her earnestly, ‘you are of the light. You must beware. There are dangers all around you. Believe this, if you believe nothing else. The forest is full of strange creatures, and there are monsters in many guises. Not all who walk on two legs are men. Not all who fly are beasts. And not all who travel the path of ages will pass through into the shadow.’

Elizabeth could make nothing of the old woman’s words, but she was impressed despite herself by the woman’s intensity and her glittering eye.

‘Mais oui,’ said the old woman, nodding. ‘You begin to believe. You have seen things in your dreams. And you are not the first. No, assuredly you are not the first. There was a young woman like you, many years ago, who came to this castle. They called her la gentille, because she was kind and good, and because she loved the flower gentiane. She wore a spray of it always in her hair. She was young and in love, and like all young women in love, she thought she could conquer everything. And she was right, for love, it can conquer everything if it is deep and true. But when the terror came, she doubted. And when the horror came, she fled. Through the forests she ran, and the wolves, they pursued her and in the end, they ran her down. Take care! Take care! There is darkness all around you. Do not falter. Do not doubt, or you too will share her fate.’

Elizabeth stared into the old woman’s eyes, chilled, despite herself, by the woman’s words. Then a touch on her arm brought her back to her senses—to the drawing room with the dancing candles and the air of bonhomie and good cheer—and she laughed at herself for being drawn in by the fortune-teller, and she agreed with the other guests that they had all been well entertained.

The woman was paid handsomely by the Count, but as she walked out of the door, Elizabeth glanced at Darcy and she could see that he was not smiling. Instead, his look was dour.

There was much laughter as the fortune-teller’s visit was discussed and then it was dismissed as attention once again turned to the game of cards. They separated into groups and played at cribbage, with Elizabeth coming second to Clothilde in her group and Darcy winning in his.

‘Darcy, he always wins,’ said Louis.

‘Not always,’ said Darcy, and a shadow crossed his face.

But then it was gone.

The evening at last drew to an end. One by one, the guests said their goodnights and withdrew to their rooms. Elizabeth excused herself and she too retired. It was cold in her room, the fire having burnt down low. She undressed quickly and was soon in bed. But as she was about to blow out the candle she caught sight of the tapestry and something caught her eye. She lifted the candle to see it better and she saw to her horror that the woman peering out from the mass of strange creatures was wearing a spray of gentian in her hair.

Chapter 7

It was as she had suspected, thought Elizabeth the following morning as she made ready to visit the hunting lodge with Darcy, the fortune-teller was one of the Count’s friends. How else could the woman have gained access to the castle, and how else could she have known about the figure in the tapestry? But even so, the evening had left its mark, and Elizabeth found it difficult to put it out of her mind. There had been something uncanny about the woman, and her story had seemed out of keeping for someone wanting to entertain a group of friends.

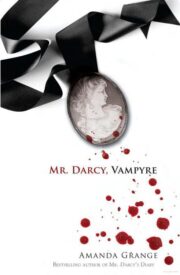

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.