‘There is one thing,’ said Elizabeth.

‘Only say its name.’

‘There is no mirror in my room.’

He became as still as a heron. At last his hands moved and he said, ‘Alas! I have no mirrors. I have been a widower for very long, you understand, and a man with no pretensions to beauty, he does not seek to fill his home with these things. Ask anything of me but this.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ said Elizabeth hurriedly, hoping she had not wounded him. ‘Thank you, there is nothing else I need.’

‘I am glad of it. The castle, it is ancient and not made for today, it is made for the old times, when my ancestors they needed a fortress from war, but I have made it my home.’

Elizabeth felt uncomfortable for a moment, wondering if he could have heard her comments on the castle’s upkeep, but then dismissed the notion as impossible.

As they continued to talk, she felt herself growing more at peace with her surroundings. The Count spoke deprecatingly of the castle, but it was clear he loved it as his home, and Elizabeth began to view it with new eyes.

‘The portraits are good, do you not think?’ asked the Count, looking up at the picture she had been examining. ‘Of them, at least, I need not be ashamed. They were painted by a local artist, a man with much talent. That one in particular is a favourite of mine. The artist has caught the fabric well. See the lace!’

‘Who are they?’ asked Elizabeth. ‘The men in the portrait?’

‘The first is of my sire, the first Polidori,’ he said, pointing to the man on the left. ‘It is from him I inherit the castle. And the one on the right is a Darcy.’

‘Yes, I thought it must be. The family resemblance is striking,’ said Elizabeth.

‘Oui, though I think that Darcy is slimmer than the man in the portrait. And more handsome, n’est-ce pas?’

He dropped into French with the ease of the English aristocracy, and Elizabeth was glad he had not lapsed into his own native tongue, which, although it bore some resemblance to French, was one she did not recognise.

‘When was it painted?’ she asked.

‘Over a hundred years ago, in 1686. Times, they were very different then. The castle was full of light and laughter. Much has changed.’ He seemed to be lost in a reverie and Elizabeth did not like to disturb him, but at last he roused himself and said, ‘But we cannot live in the past. We must accept what we have in the present, and that is not so bad, with a visit from friends to look forward to. My housekeeper, she will be doing what she can to improve the castle’s appearance in honour of my valued guests. If it will not discommode you greatly, will you take your meal at noontide in your room and remain there until we eat at six o’clock? We keep early hours at the castle. I believe, in England, you call them country hours.’

Elizabeth said that it would not discommode her at all and the Count excused himself. She soon followed him from the room, feeling more cheerful than she had done since arriving at the castle.

She found Annie in her room, pressing her evening gowns with a flat iron heated on the fire, and the homely scene further reassured her.

‘It will be lunch on a tray today, Annie,’ she said, ‘and then there will be guests for dinner. I will wear my amber silk, I think, with plenty of petticoats. It’s very cold away from the fires. And I will have my cashmere shawl.’

‘Will you wear the amber beads or the gold necklace?’ Annie asked.

‘The beads, I think,’ said Elizabeth, recalling the Count’s shabby clothes: she wanted Darcy to be proud of her, but she did not want to look too fine.

‘Very good, Ma’am.’

One of the maids soon arrived with a tray of hot, steaming stew which tasted exactly the same as the previous night’s meal, and Elizabeth thought of how shocked her mother would have been at this deficiency in the housekeeping, then fell to musing about the Count’s wife. She wondered what the Countess had been like and thought it a tragedy she had died, for she suspected that, if the Countess had still been alive, the castle would have been better looked after, even if the Count’s fortunes had dwindled.

After her lunch, Elizabeth finished her letter to Jane, but alas, she knew she could not post it in such an out of the way place and that she would have to wait until they returned to civilisation before she could send it.

There was no dressing room, the bedroom filling all of the turret, but one of the footmen carried a hip bath upstairs and the maids brought jugs of hot water so that Elizabeth could take a bath. It was a delight to soak in the hot, soapy water and soothe away all the aches and pains caused by the jostling of the coach the day before.

By three o’clock there were already sounds of commotion from below, gusting in through the door whenever Annie opened it to fetch hot water, and Elizabeth found herself looking forward to the evening. Scented, warm, and delicately flushed, she climbed out of the bath and dried herself before the fire, then set about dressing for the evening. Her amber gown suited her complexion, and with its round neck, it complemented the shape of her face. Annie dressed her hair and then said, ‘There,’ standing back with satisfaction.

‘Thank you, Annie,’ she said.

She found it strange going downstairs without first looking in the mirror to make sure she was dressed to her own satisfaction, but there was no help for it and so, putting on her gloves and picking up her shawl, she went downstairs.

The castle looked brighter than formerly, with a profusion of candles lighting the hall and bowls of wildflowers set on the tables. There was a murmur of voices and, from outside, the sound of horses and carriage wheels. The door opened and a draught swirled into the hall. With it came the sound of laughter.

‘You’re looking very lovely,’ said Darcy, materialising beside her. ‘Shall we go in?’

She took his arm and they entered the drawing room.

It looked altogether different. Candles were set on every surface and the room had a bright and welcoming air. The fire roared in the fireplace, giving out not only heat but light, and the sound of conversation bubbled everywhere. It was in a foreign tongue, but it sounded good humoured and lively.

Gradually the hubbub died down and one by one the Count’s guests turned towards the door. They were mostly men, dressed in shabby, comfortable clothes which nevertheless had the air of being their best. The few women amongst them were all dressed in woollen clothes that were shabby too, and Elizabeth felt conscious of being finer than her neighbours.

It was the first time she had had such a feeling since the start of their wedding tour. In France she had felt positively dowdy by the side of the butterfly-like creatures who flitted about the ballrooms and salons, but here she felt like an exotic bird in a room full of sparrows. She quickly saw that the Count’s guests did not resent the fact, but that they liked seeing a bride in all her glory.

‘So you are the woman who has captured Darcy?’ said one of the men jovially, coming forward. ‘It is easy to see why he has lost his heart.’

The introductions were made, and Elizabeth was made to feel very welcome. For the first time since her marriage, Elizabeth felt she was in a world she could understand. Although the clothes, the customs, and the castle might be unfamiliar, she was being given the courtesies always accorded to a bride on her wedding tour. She was the centre of attention, her every word was being listened to with great interest.

‘You must tell us how you met,’ said Gustav. ‘We have heard nothing about it.’

‘We never hear of anything here!’ said Clothilde.

‘Yes, do tell us,’ said Isabella.

‘Indeed,’ said Frederique.

‘We met in Hertfordshire,’ said Elizabeth, ‘when Darcy’s friend rented a house in my neighbourhood. Darcy attended the local assembly with his friend…’

‘And it was love at first sight. I comprehend!’ said Louis.

Elizabeth laughed.

‘Far from it!’ she said.

‘No? But what is this? Darcy, you did not fall in love at once with the beautiful Elizabeth?’ He turned to Elizabeth. ‘If I had been there, I would have prostrated myself at your so-charming feet.’

‘When, then, did Darcy see the error of his ways?’ asked Gustav.

‘It was not until many months later,’ said Elizabeth.

‘No? Darcy! You are a veritable blockhead!’ said Frederique.

Darcy smiled.

‘Ah, yes, my friend, you can afford to smile, you have at last won the hand of the beautiful Elizabeth and you bring her to us as your bride.’

‘But how did it happen?’ asked Carlotta. ‘You must tell us how Darcy changed his mind.’

Nothing would do for them but to hear a full recital. Elizabeth left out any mention of Georgiana and Wickham, and she passed lightly over Lydia’s elopement, saying only that Darcy had come to the aid of her sister when that sister found herself in difficulties a long way from home.

They were still asking her questions when dinner was announced, and over that meal, which consisted of venison, root vegetables, and partridge, they teased out more information about Elizabeth’s home in Hertfordshire. Gustav announced that he had been to England many years ago and he discussed its merits with Elizabeth.

The women were engaging and the men were attentive, so that Elizabeth felt herself charmed. For all their shabby clothes, they knew how to set her at her ease, and the men knew how to flatter her delicately and how to make her laugh.

After dessert, the port was passed round and the ladies withdrew. The Count’s female guests were full of admiration for Elizabeth’s gown and they were eager to hear about the Paris fashions.

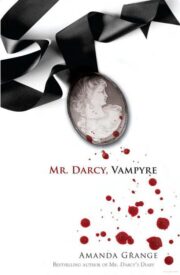

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.