The inn was so small that friendship was inevitable, and the four of them were soon engaged in conversation.

‘Have you come far?’ asked Mr Cedarbrook, as their host brought in a large bowl of something savoury and proceeded to ladle appetising soup into clay bowls, placing large hunks of crusty bread on the plates next to them.

‘From Paris,’ said Darcy.

‘Ah, Paris! How I love Paris,’ said Mrs Cedarbrook.

‘Humph,’ said her husband, tasting his soup. He made an appreciative noise and took another spoonful. ‘Big cities are not for me.’

‘My husband is a botanist,’ explained Mrs Cedarbrook. ‘He prefers the countryside. We are on a walking tour, collecting plants.’

‘New species,’ said her husband as he broke off a piece of bread. ‘There are plenty of them in the Alps. What do you do?’ he asked Darcy.

‘I am a gentleman of leisure,’ said Darcy.

‘A man needs a hobby, even so,’ said Mr Cedarbrook. ‘You should take up botany.’

‘My dear, not everyone wants to be a botanist,’ said his wife.

‘Can’t think why not,’ he returned.

Mrs Cedarbrook smiled indulgently, but accompanying the look was also an expression of good humour and common sense. She reminded Elizabeth of her Aunt Gardiner, who treated Mrs Bennet’s foibles in much the same way as Mrs Cedarbrook treated her husband’s eccentricities.

‘Do you always travel together?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘We do now,’ said Mrs Cedarbrook. ‘When the children were younger I stayed at home because I did not like to be away from them for months at a time, but now that they have all married and have homes of their own, I enjoy our journeys and I like to see something of the world.’

‘And what do you do when your husband is studying plants?’ asked Darcy.

‘I have my sketchbook and my watercolours, and I make a pictorial record of everything we see,’ she replied.

‘And very useful it is, too,’ said her husband.

They talked of their experiences in the Alps over the meal, sharing their pleasure in the scenery. They also shared with each other information about the journey, for they had approached the inn from different directions, and so they knew what difficulties their fellow guests would face on the following day.

When they had finished their meal, their host brought in a bottle of some local spirit and Mrs Cedarbrook said to Elizabeth, ‘I think it is time for us to withdraw.’

‘Gladly,’ said Elizabeth.

It was a long time since she had had a woman to talk to—a sensible, mature woman—and she felt herself in need of someone to turn to.

As there was no withdrawing-room, they retired to Mrs Cedarbrook’s chamber and there they sat and talked. All the time, Mrs Cedarbrook watched Elizabeth and after a while she said, ‘Something is troubling you, my dear. Can I help?’

‘No, it is nothing,’ said Elizabeth.

‘I have two grown up daughters and I can tell that something is wrong. Will you not trust me?’

Elizabeth was longing to do so, but she did now know how to begin.

‘You are from Hertfordshire, I think you said?’ prompted Mrs Cedarbrook.

‘Yes, that’s right, from a small town called Meryton,’ said Elizabeth.

‘I do not know the town, but I have passed through Hertfordshire often on various journeys. It is a very beautiful county, but very different to the Alps. You are a long way from home. Do you not find it lonely here, where there are so few people?’

‘I have my husband,’ said Elizabeth.

‘Of course. But sometimes a woman needs another woman to talk to.’

Elizabeth said nothing, but she had been thinking exactly the same thing. She had been troubled for some time, and she found it difficult to keep her feelings to herself, because at home she had always had someone to talk to.

‘You are a long way from your mother,’ said Mrs Cedarbrook.

‘Yes, I am,’ said Elizabeth.

She gave a rueful smile as she thought of her mother.

Mrs Cedarbrook said, ‘Ah,’ quietly, and added, ‘And your friends.’

‘Yes,’ said Elizabeth with a sigh.

‘You must miss them,’ said Mrs Cedarbrook kindly.

‘I do. But not as much as I miss my sister.’

‘If you need someone to talk to, my dear, I am here.’

Elizabeth looked at her uncertainly and then came to a decision. Mrs Cedarbrook was a stranger, but she was a sympathetic woman and Elizabeth needed to confide in someone. Her friends and family were a long way away and she had no one else to turn to in her need for a listening ear and, more importantly, some advice.

‘You are worried about something,’ said Mrs Cedarbrook gently.

‘It is only…’ said Elizabeth, not knowing how to begin. ‘It is just that…’

‘Yes, my dear?’

‘It is just that, sometimes, I don’t understand my husband.’

‘You have been married long?’

‘No, we are only just married. We are on our wedding tour.’

‘You seem very happy together. It is not difficult to see that your husband loves you very much.’

‘I wonder,’ said Elizabeth, looking down at her hands, which were pleating the fabric of her skirt in her lap.

‘What makes you say that?’ asked Mrs Cedarbrook.

‘It is just that he hasn’t so much as touched me in all this time. He’s attentive and friendly and considerate, we have a great deal to say to each other, and the way he looks at me—you have seen the way he looks at me.’

‘Yes, I have.’

‘But at night, when we could be alone, he avoids me.’

Mrs Cedarbrook looked at her thoughtfully.

‘You are very young. Perhaps he is just giving you time to adjust to your new life. Tempt him, my dear. You are very lovely, and there isn’t a man alive who could resist you if you put your mind to it.’

‘That’s just it,’ said Elizabeth. ‘I don’t know how.’

‘You are a woman in love, you will know how when the time comes. Go to his room if he will not come to yours. It will not be long before you are happy, I am sure.’

‘You have taken a load from my mind,’ said Elizabeth. ‘Just to be able to talk about it has been a help.’

There was a noise from below.

‘I think the gentlemen are coming to the end of their conversation. Go now, my dear, and I am sure your problems will soon be over.’

The two women rose and Elizabeth returned to her own room. Annie helped her to undress and then, saying, ‘Thank you, Annie,’ Elizabeth waited only for her maid to leave the room before she went through the interconnecting door into her husband’s room. She had hoped to find Darcy there, but the room was empty, save for a faint, lingering scent of him.

On the washstand, his valet had laid out his brushes and razor, and Elizabeth went over to them and ran her hands over them. These were the things he had touched, and she let her fingers linger there. Her eyes wandered round the small, rustic apartment until they came to rest on the window. It had been left open. The night air was fresh but cold, and it carried a hint of frost. She went over to the window and prepared to close it, but her hand rested on the catch for a moment and she looked out over the tranquil, moonlit landscape. The lake was shining placidly in the silver light and, far off, trees were silhouetted against the white backdrop of the mountain. Hanging above it was a gibbous moon, phosphorescent in the darkness.

Her attention was attracted by movement close at hand and she saw the dark shape of a bird—no, a bat—heading towards the window. She closed it quickly, leaving the bat to hover outside. As she looked at it she was seized with a strange feeling. She thought how lonely it must feel, being shut out, being a part and yet not a part of the warmth and light within.

Then the bat turned and flew away and the moment was broken, and she went back to the other side of the room, warming herself by the fire.

There was still no sign of Darcy.

She returned to her own room, and to her astonishment, she found him standing on the hearthrug. She had not heard his footsteps in the corridor, but her surprise quickly gave way to a sense of anticipation. He had come to her after all. She went closer and she felt the tension in him, as though he was trying to hold back some great force by sheer strength of will. She shivered, but not with cold. She could hear his shallow, uneven breathing, and he leaned towards her…

…and then she saw his hands clench as if he had fought an inner battle and emerged in some way victorious, but as if the victory had brought him no pleasure and had cost him dear. He kissed her gently on the cheek, the faintest brush of his lips, and said, ‘Good night, Elizabeth,’ Then, going into his own room, he shut the door.

She could still feel the warmth of his lips on her skin, and she raised her hand to them in an effort to hold the feeling. But gradually it faded, until there was nothing left of it.

She shivered, and looking round, she noticed that the window in her room too was open. She went to shut it, then she climbed into bed. She lay awake for a long time before she at last she fell asleep.

The morning sunlight streaming through a crack in the shutters woke her. She was confused for a moment, not recognising the room, then she remembered that she was in the Alps and she jumped out of bed. She threw back the shutters to see that the sky was a startling blue and that the mountains were rising majestically against it.

Her eyes wandered downwards, to the meadows and wildflowers that surrounded the taverna, and then to the still and placid lake. When she looked more closely, she could see that someone was swimming there. Her heart leapt as she saw that it was Darcy. She longed to join him, and although she thought, to begin with, that she could not possibly do any such thing, she soon changed her mind and thought, Why not?

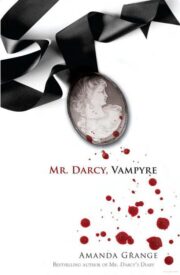

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.