‘So I have, a long time ago. You’re right, they don’t matter.’

‘But something matters,’ she said, bringing her mare to a standstill, ‘because you are not happy.’

He looked surprised.

‘I am happy,’ he said.

‘Then you are not easy in our mind,’ she persevered. ‘Otherwise why would you want your uncle’s advice?’

Again he thought before speaking.

‘Elizabeth, there are things you don’t yet know,’ he said with a frown.

‘About you?’

‘About me, and my family.’

‘You mean there are skeletons in the closet?’ she asked, patting her mare’s neck.

He gave a ghost of a smile.

‘Not skeletons, no,’ he said. ‘But I think I might have underestimated the problems we will face. For myself, it doesn’t matter, but for you… I want to protect you, I want to make you happy.’

‘You do.’

‘No, not entirely. I’ve seen you looking at me, puzzled, a few times since we married.’

She could not deny it.

‘That’s because I don’t always understand you,’ she said.

‘I don’t always understand myself.’

‘You have always been a difficult man to fathom,’ she agreed. ‘Even at the Netherfield ball, I could not make you out. And I think that recently, you have grown more perplexing rather than less so. I hope your uncle can help.’

‘I think you will like him, and I think you will like the Alps. The scenery is unlike anything you have ever seen before.’ Then his eyes laughed and he said, ‘Your mother would certainly like him. He lives in a castle.’

‘A castle?’ she asked, impressed despite herself. ‘Is it finer than Pemberley?’

‘Bigger, certainly.’

‘Finer than Rosings?’

‘More imposing, at least.’

The horses began to trot more quickly, as if sensing the lightening in their riders’ moods, and before long, they reached a wider open space.

‘And what of the chimney piece?’ asked Elizabeth teasingly.

‘It is the most impressive chimney piece I have ever seen; the sort of chimney piece that would send Mr Collins into raptures.’

‘Then I beg you will not tell him about it, or he will find a way to visit your uncle, and drag poor Charlotte with him,’ said Lizzy, laughing. ‘What is his name, this uncle? Is he a Darcy or a Fitzwilliam?’

‘He comes from… an older branch of the family,’ he said. ‘He is an uncle a few times removed. He is neither a Fitzwilliam nor a Darcy. His name is Count Polidori.’

‘A count?’ asked Lizzy, amused. ‘Then we must definitely not tell Mama about him, or she will be introducing him to Kitty!’

‘He is rather too old for Kitty,’ he said.

‘That is a relief. Poor Kitty has had enough to cry about these last few months, with Papa saying he would keep a careful watch over her and never let her out! It took a great deal of soothing to make her realise that he was joking. When do you expect us to leave for the mountains?’ she asked.

‘That depends. We can go as soon or as late as you wish. Have you seen enough of Paris or would you like to stay?’

‘I think I have seen all I need to see,’ she said. ‘It is very elegant, despite the destruction wrought by the revolution. The people too have surprised me, but…’

‘But?’

‘I find I do not really like it here. The buildings are all very fine, but I am longing for green fields once again.’

‘Then we will make our preparations and set out as soon as they are complete.’

Chapter 4

The weather was fine when they left Paris. It was a golden October, with plenty of sunshine and warm, drowsy days. They set out at a leisurely pace, enjoying the journey. Elizabeth travelled in the coach as it passed through the city and headed in a south-easterly direction. They stopped for lunch at an inn near Fontainebleau and then Elizabeth took to horseback, riding through the forest beside Darcy. The whitebeams were starting to lose their leaves, creating openness above them, and the air had a clarity that made the colours sing.

They passed the chateau of Fontainebleau and Elizabeth looked at it in wonder. It dwarfed Pemberley and Rosings, too.

‘At least the revolution didn’t destroy this,’ she said.

She had seen a great deal of destruction in Paris, with buildings defaced or demolished, but the palace was still intact, rapturous in its beauty. It had graceful proportions and elegant lines, ornamented with the curve of a horseshoe staircase at its front. And surrounding the palace were the greens and blues of the gardens and lake.

‘No, not the outside, but the inside has been ransacked and the furniture sold. François would not recognise it now, nor Louis, nor Marie Antoinette.’

He spoke about them as if he knew them, but Elizabeth’s education, governess-less though it had been, was sufficient to tell her that he meant the French kings and queens of centuries gone by.

‘Autumn was always the time for Fontainebleau,’ he said. ‘That was when the Court came here to hunt. But not anymore. Nothing lasts. It all fades away. Only the trees remain.’ He pointed one of them out to her, an ancient tree, standing alone. ‘I used to climb that tree as a boy,’ he said. ‘It was perfect for my purposes. The lower branches were just low enough for me to be able to reach them by jumping, if not on the first attempt, then on the second or third, and the topmost branches were strong enough to bear my weight. When I reached them, I would hold on to the trunk and look out over the surrounding countryside and pretend I was on a ship and that I had just climbed the mast, looking for land.’

‘You may climb it now if you like!’ she said. ‘I will wait.’

He laughed.

‘I doubt the branches would bear my weight. It was a long time ago.’

She liked to hear of his childhood, and as they rode on, he told her more about his boyhood pursuits. She responded with tales of her own childhood, games of chase with her large family of sisters on the Longbourn lawn and rainy afternoons curled up on the window seat in the library with a book.

Elizabeth patted her mare’s neck as they came to a crossroads and turned south, the carriages rolling along behind them. Darcy, watching Elizabeth said, ‘Has Snowfall won you over? Do you like riding?’

‘How could I not with such a mount?’ said Elizabeth. ‘But—’

She shifted a little in her saddle.

‘Saddle sore?’ he asked.

‘Yes! I am not used to it, you know.’

‘Would you rather walk?’

‘I think so, for a little while, anyway.’

He helped her to dismount and then dismounted beside her, and they walked on, leading their horses, until Elizabeth at last tired and took her seat once more in the coach.

As they travelled south through France, the Alps drew steadily closer.

‘Twice now I have been deprived of a promised visit to the Lake District, but both times I have been glad to change my destination. I never thought anything could be so beautiful,’ she said.

She raised her eyes to their summits, which were iced with snow.

‘You must have seen pictures of them,’ said Darcy.

‘Pictures, yes, but they didn’t prepare me for their scale or grandeur,’ she said.

As day followed day, they left the lowlands behind and began to climb, following a winding road through the foothills of the mountains which gave extensive views at every turn. Against the backdrop of the mountains there were tall trees and shady glens, and here and there, they saw mountain goats. There were flowers still blooming in the meadows. Butterflies flitted between the gentians, harebells, and saxifrage, their iridescent blue and yellow wings catching the light.

From time to time, they came across cool, bubbling springs at which they stopped to drink.

Darcy knew the way, having travelled the route before, and as the light started to fade at the end of each day, he led them to a homely cottage where they could shelter, having them safely inside before sunset.

At the end of several days’ travelling, they stopped for the night at a small inn.

‘It’s not like the inns in England,’ said Darcy as they approached.

‘It’s delightful,’ said Elizabeth.

It was set amidst the mountains beside a mirror-like lake. She ran her eyes over the rustic building with its gaily painted shutters, its blooming window boxes, and its overhanging eaves.

They were welcomed warmly with genuine hospitality. The size of their retinue at first caused some consternation, but the problem was quickly solved by the judicious use of outbuildings which nestled close by the inn.

Elizabeth’s room was homely, with pine furniture. There was a picture over the bed, but the real picture in the room was the view. Framed by the window, it was magnificent. Elizabeth rested her arms on the window ledge and watched the sun setting. It turned the sky golden as its last rays blazed out, then flooded it with orange and red as the sky around it grew darker, changing from blue to purple, and then, as the sun sank at last, to black. The white finger of the mountain could still be seen, glowing softly in the ethereal light of the stars that pricked the sky. Elizabeth watched it still, delighting in the novelty and the splendour of its majesty, until the wind blew cold and she drew the curtain.

She washed and changed and then went down to dinner. The dining room was a simple apartment with only three tables, each flanked with benches. But the room was pretty, with long gingham cushions on the benches and gingham curtains at the windows.

Despite the remoteness of the place, the Darcys were not the only guests. A middle aged English couple, a Mr and Mrs Cedarbrook, were also staying there. They had an air of solid respectability about them and whilst her husband’s expression was absent-minded, Mrs Cedarbrook’s face wore a sensible aspect. They were dressed in good but unostentatious clothes, with Mrs Cedarbrook wearing a cashmere shawl over her cambric gown and Mr Cedarbrook wearing a well-tailored coat and breeches with a simply folded cravat.

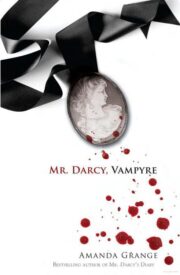

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.