Not enough.

“I’m more approachable when I’m sotted?” he tried to joke.

“Or seasick,” she said kindly.

He laughed at that. “I’m lucky the weather is so fair. I’m told the seas are usually much less forgiving. The captain said that crossing from Liverpool to Dublin is often more difficult than the entire passage from the West Indies to England.”

Her eyes lit with interest. “That can’t be.”

Thomas shrugged. “I only repeat what he told me.”

She considered this for a moment, then said, “Do you know, this is the farthest I have ever been from home?”

He leaned a little closer. “Me, too.”

“Really?” Her face showed her surprise.

“Where would I have gone?”

He watched with amusement as she considered this. Her face moved through a number of expressions, and then finally she said, “You are so fond of geography. I would have thought you would travel.”

“I would like to have done.” He watched the sunset. It was melting away too quickly for his tastes. “Too many responsibilities at home, I suppose.”

“Will you travel if-” She cut herself off, and he did not need to be looking at her to picture the expression on her face precisely.

“If I am not the duke?” he finished for her.

She nodded.

“I expect so.” He gave a little shrug. “I am not sure where.”

Amelia turned to him suddenly. “I have always wanted to see Amsterdam.”

“Really.” He looked surprised. Maybe even intrigued. “Why is that?”

“All those lovely Dutch paintings, I think. And the canals.”

“Most people travel to Venice for the canals.”

She knew that, of course. Maybe that was part of the reason she’d never wanted to go there. “I want to see Amsterdam.”

“I hope you shall,” he said. He was quiet for just long enough to make the moment noticeable. And then, softly: “Everybody should be able to realize at least one of their dreams.”

Amelia turned. He was looking at her with the most gentle expression. It nearly broke her heart. What was left of it, at least. So she looked away. It was too hard otherwise. “Grace went below,” she said.

“Yes, you’d said.”

“Oh.” How embarrassing. “Yes, of course. The fan.” He did not reply, so she added, “There was something about soup, as well.”

“Soup,” he repeated, shaking his head.

“I could not decipher the message,” Amelia admitted.

He gave her a rather dry half smile. “Now there is one responsibility I am not sorry to shed.”

A little laugh rose in Amelia’s throat. “Oh, I’m sorry,” she said quickly, trying to force it down. “That was terribly rude of me.”

“Not at all,” he assured her. His face dipped closer to hers, his expression terribly conspiratorial. “Do you think Audley will have the nerve to send her away?”

“You didn’t.”

He held up his hands. “She’s my grandmother.”

“She is his, as well.”

“Yes, but he doesn’t know her, lucky chap.” He leaned toward her. “I suggested the Outer Hebrides.”

“Oh, stop.”

“I did,” he insisted. “Told Audley I was thinking of buying something there, just so I could maroon her.”

This time she did laugh. “We should not be speaking of her this way.”

“Why is it,” he mused, “that everyone I know speaks of crotchety old ladies who, underneath their acerbic exteriors, have a heart of gold?”

She looked at him with amusement.

“Mine doesn’t,” he said, almost as if he could not quite believe the unfairness of it all.

She tried not to smile. “No.” She gave up. She sputtered, then grinned. “She doesn’t.”

He looked at her, and their eyes caught each other’s amusement, and they both burst out laughing.

“She’s miserable,” Thomas said.

“She doesn’t like me,” Amelia said.

“She doesn’t like anyone.”

“I think she likes Grace.”

“No, she just dislikes her less than she dislikes everyone else. She doesn’t even like Mr. Audley, even as she works so tirelessly to gain him the title.”

“She doesn’t like Mr. Audley?”

“He detests her.”

She shook her head, then looked back out at the sunset, which was in its death throes over the horizon. “What a tangle.”

“What an understatement.”

“What a knot?” she offered, feeling very nautical.

She heard him let out a little snuff of amusement, and then he rose to his feet. She looked up; he was blotting out the last shafts of the sun. Indeed, he seemed to fill her entire vision.

“We could have been friends,” she heard herself say.

“Could?”

“Would,” she corrected, and she was smiling. It seemed the most amazing thing. How was it possible she had anything to smile about? “I think we would have been friends, if not for…If all this…”

“If everything were different?”

“Yes. No. Not everything. Just…some things.” She began to feel lighter. Happier. And she had not the slightest clue why. “Maybe if we’d met in London.”

“And we hadn’t been betrothed?”

She nodded. “And you hadn’t been a duke.”

His brows rose.

“Dukes are very intimidating,” she explained. “It would have been so much easier if you hadn’t been one.”

“And your mother had not been engaged to marry my uncle,” he added.

“If we’d just met.”

“No history between us.”

“None.”

His brows rose and he smiled. “If I’d seen you across a crowded room?”

“No, no, nothing like that.” She shook her head. He was not getting this at all. She wasn’t talking about romance. She couldn’t bear to even think of it. But friendship…that was something else entirely. “Something far more ordinary,” she said. “If you’d sat next to me on a bench.”

“Like this one?”

“Perhaps in a park.”

“Or a garden,” he murmured.

“You would sit down next to me-”

“And ask your opinion of Mercator projections.”

She laughed. “I would tell you that they are useful for navigation but that they distort area terribly.”

“I would think-how nice, a woman who does not hide her intelligence.”

“And I would think-how lovely, a man who does not assume I have none.”

He smiled. “We would have been friends.”

“Yes.” She closed her eyes. Just for a moment. Not for long enough to allow her to dream. “Yes, we would.”

He was quiet for a moment, and then he picked up her hand and kissed it. “You will make a spectacular duchess,” he said softly.

She tried to smile, but it was difficult; the lump in her throat was blocking her way.

Then, softly-but not so softly that she was not intended to hear-he said, “My only regret is that you never were mine.”

Chapter 16

The following day, at the Queen’s Arms, Dublin

Do you think,” Thomas murmured, leaning down to speak his words in Amelia’s ear, “that there are packets leaving directly from Dublin port, heading to the Outer Hebrides?”

She made a choking sound, followed by a very stern look, which amused him to no end. They were standing, along with the rest of their traveling party, in the front room of the Queen’s Arms, where Thomas’s secretary had arranged for their rooms on the way to Butlersbridge, the small village in County Cavan where Jack Audley had grown up. They had reached the port of Dublin in the late afternoon, but by the time they collected their belongings and made their way into town, it was well after dark. Thomas was tired and hungry, and he was fairly certain that Amelia, her father, Grace, and Jack were as well.

His grandmother, however, was having none of it.

“It is not too late!” she insisted, her shrill voice filling every corner of the room. They were now on minute three of her tantrum. Thomas suspected that the entire neighborhood had been made aware that she wished to press on toward Butlersbridge that evening.

“Ma’am,” Grace said, in that calm, soothing way of hers, “it is past seven. We are all tired and hungry, and the roads are dark and unknown to us.”

“Not to him,” the dowager snapped, jerking her head toward Jack.

“I am tired and hungry,” Jack snapped right back, “and thanks to you, I no longer travel the roads by moonlight.”

Thomas bit back a smile. He might actually grow to like this fellow.

“Don’t you wish to have this matter settled, once and for all?” the dowager demanded.

“Not really,” Jack answered. “Certainly not as much as I want a slice of shepherd’s pie and a tankard of ale.”

“Hear hear,” Thomas murmured, but only Amelia heard.

It was strange, but his mood had been improving the closer they got to their destination. He would have thought he’d grow more and more tortured; he was about to lose everything, after all, right down to his name. By his estimation, he ought to be snapping off heads by now.

But instead he felt almost cheerful.

Cheerful. It was the damnedest thing. He’d spent the entire morning on deck with Amelia, swapping tales and laughing uproariously. It had been enough to make his stomach forget to be seasick.

Thank the Lord, he thought, for very large favors. It had been a close thing, the night before-keeping the three bites he’d eaten of supper in his belly, where it belonged.

He wondered if his odd amiability was because he had already accepted that Jack was the rightful duke. Once he had stopped fighting that, he just wanted to get the whole bloody mess over and done with. The waiting, truly, was the hardest part.

He’d gotten his affairs in order. He’d done everything required for a smooth transition. All that was left was to get it done. And then he could go off and do whatever it was he would have done had he not been tied to Belgrave.

Somewhere in the midst of his ponderings he realized that Jack was leaving, presumably to get that slice of shepherd’s pie. “I do believe he has the right idea of it,” Thomas murmured. “Supper sounds infinitely more appealing than a night on the roads.”

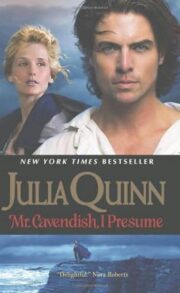

"Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" друзьям в соцсетях.