He supposed they had all turned out well. He’d liked Eton and loved Cambridge, and if he’d liked to have defended his country as Jack had-well, it did seem that His Majesty’s army had acquitted itself just fine without him. Even Amelia…

He closed his eyes for a moment, allowing the pitch and roll of the boat to play games with his balance.

Even Amelia would have turned out to be an excellent choice. He felt like an idiot for having taken so long to know her.

All those decisions he’d not been allowed to make…He wondered if he would have done a better job with them himself.

Probably not.

Off at the bow, he could see Grace and Amelia, sitting together on a built-in bench. They were sharing a cabin with the dowager, and since she had barricaded herself inside, they had elected to remain out. Lord Crowland had been given the other cabin. He and Jack would bunk below, with the crew.

Amelia didn’t seem to notice that he was watching her, probably because the sun would have been in her eyes if she had looked his way. She’d taken off her bonnet and was holding it in her hands, the long ribbons flapping in the wind.

She was smiling.

He’d been missing that, he realized. He hadn’t seen her smile on the journey to Liverpool. He supposed she had little reason to. None of them did. Even Jack, who had so much to gain, was growing ever more anxious as they drew closer to Irish soil.

He had his own demons waiting at the shore, Thomas suspected. There had to be a reason he’d never gone back.

He turned and looked west. Liverpool had long since disappeared over the horizon, and indeed, there was nothing to see but water, rippling below, a kaleidoscope of blue and green and gray. Strange how a lifetime of looking at maps did not prepare a man for the endless expanse of the sea.

So much water. It was difficult to fathom.

This was the longest sea voyage he’d ever taken. Strange, that. He’d never been to the Continent. The grand tours of his father’s generation had been brought to a halt by war, and so any last educational flourishes he had made were on British soil. The army had been out of the question; ducal heirs were not permitted to risk their lives on foreign soil, no matter how patriotic or brave.

Another item that would have been different, had that other ship not gone down: he’d have been off fighting Napoleon; Jack would have been held at home.

His world was measured in degrees from Belgrave. He did not travel far from his center. And suddenly it felt so limited. So limiting.

When he turned back, Amelia was sitting alone, shading her eyes with her hand. Thomas looked about, but Grace was nowhere in sight. No one was about, save for Amelia and a young boy who was tying knots in ropes at the bow.

He had not spoken to her since that afternoon at Belgrave. No, that was not true. He was fairly certain they had exchanged a few excuse me’s and perhaps a good morning or two.

But he had seen her. He’d watched her from afar. From near, too, when she was not looking.

What surprised him-what he had not expected-was how much it hurt, just to look at her. To see her so acutely unhappy. To know that he was, at least in part, the cause.

But what else could he have done? Stood up and said, Er, actually I think I would like to marry her, after all, now that my future is completely uncertain? Oh yes, that would have met with a round of applause.

He had to do what was best. What was right.

Amelia would understand. She was a smart girl. Hadn’t he spent the last week coming to the realization that she was far more intelligent than he’d thought? She was practical, too. Capable of getting things done.

He liked that about her.

Surely she saw that it was in her best interest to marry the Duke of Wyndham, whoever he might be. It was what had been planned. For her and for the dukedom.

And it wasn’t as if she loved him.

Someone gave a shout-it sounded like the captain-and the young boy dropped his knots and scrambled away, leaving himself and Amelia quite alone on deck. He waited a moment, giving her the chance to leave, if she did not wish to risk being trapped into conversation with him. But she did not move, and so he walked toward her, offering her a deferential nod when he reached her side.

“Lady Amelia.”

She looked up, and then down. “Your grace.”

“May I join you?”

“Of course.” She moved to the side, as far as she could while still remaining on the bench. “Grace had to go below.”

“The dowager?”

Amelia nodded. “She wished for Grace to fan her.”

Thomas could not imagine that the thick, heavy air belowdeck would be improved by pushing it about with a fan, but then again, he doubted his grandmother cared. She was most likely looking for someone to complain to. Or complain about.

“I should have accompanied her,” Amelia said, not quite ruefully. “It would have been the kind thing to do, but…” She exhaled and shook her head. “I just couldn’t.”

Thomas waited for a moment, in case she wished to say anything more. She did not, which meant that he had no further excuse for his own silence.

“I came to apologize,” he said. The words felt stiff on his tongue. He was not used to apologizing. He was not used to behaving in a manner that required apology.

She turned, her eyes finding his with startling directness. “For what?”

What a question. He had not expected her to force him to lay it out. “For what happened back at Belgrave,” he said, hoping he would not have to go into more detail. There were certain memories one did not wish to keep in clarity. “It was not my intention to cause you distress.”

She looked out over the length of the ship. He saw her swallow, and there was something melancholy in the motion. Something pensive, but not quite wistful.

She looked too resigned to be wistful. And he hated that he’d had any part in doing that to her.

“I…am sorry,” he said, the words coming to him slowly. “I think that you might have been made to feel unwanted. It was not my intention. I would never wish you to feel that way.”

She kept staring out, her profile toward him. He could see her lips press and purse, and there was something mesmerizing in the way she blinked. He’d never thought there could be so much detail in a woman’s eyelashes, but hers were…

Lovely.

She was lovely. In every way. It was the perfect word to describe her. It seemed pale and undescriptive at first, but upon further reflection, it grew more and more intricate.

Beautiful was a daunting thing, dazzling…and lonely. But not lovely. Lovely was warm and welcoming. It glowed softly, sneaking its way into one’s heart.

Amelia was lovely.

“It’s growing dark,” she said, changing the subject. This, he realized, was her way of accepting his apology. And he should have respected that. He should have held his tongue and said nothing more, because clearly that was what she wanted.

But he couldn’t. He, who had never found cause to explain his actions to anyone, was gripped by a need to tell her, to explain every last word. He had to know, to feel it in his very soul that she understood. He had not wanted to give her up. He hadn’t told her to marry Jack Audley because he wanted to. He’d done it because…

“You belong with the Duke of Wyndham,” he said. “You do, just as much as I thought I was the Duke of Wyndham.”

“You still are,” she said softly, still staring ahead.

“No.” He almost smiled. He had no idea why. “We both know that isn’t true.”

“I don’t know anything of the sort,” she said, finally turning to face him. Her eyes were fierce, protective. “Do you plan to give up your birthright based upon a painting? You could probably pull five men out of the rookeries of London who could pass for someone in one of the paintings at Belgrave. It is a resemblance. Nothing more.”

“Jack Audley is my cousin,” he said. He had not uttered the words many times; there was a strange relief in doing so. “All that remains to be seen is if his birth was legitimate.”

“That is still quite a hurdle.”

“One that I am sure will be easily reached. Church records…witnesses…there will be proof.” He faced front then, presumably staring at the same spot on the horizon. He could see why she’d been mesmerized. The sun had dipped low enough so one could look in its direction without squinting, and the sky held the most amazing shades of pink and orange.

He could look at it forever. Part of him wanted to.

“I did not think you were a man to give up so easily,” she said.

“Oh, I’m not giving up. I’m here, aren’t I? But I must make plans. My future is not what I’d thought.” Out of the corner of his eye he saw her begin to protest, so he added, with a smile, “Probably.”

Her jaw tensed, then released. Then, after a few moments, she said, “I like the sea.”

So did he, he realized, even with his queasy stomach. “You’re not seasick?” he asked.

“Not at all. Are you?”

“A little,” he admitted, which made her smile. He caught her eye. “You like when I am indisposed, don’t you?”

Her lips pressed together a bit; she was embarrassed.

He loved that.

“I do,” she confessed. “Well, not indisposed, exactly.”

“Weak and helpless?” he suggested.

“Yes!” she replied, with enough enthusiasm that she immediately blushed.

He loved that, too. Pink suited her.

“I never knew you when you were proud and capable,” she hastened to add.

It would have been so easy to pretend to misunderstand, to say something about how they had known each other all of their lives. But of course they had not. They had known the other’s name, and their shared destiny, but that was all. And Thomas was finally coming to realize that it was not much.

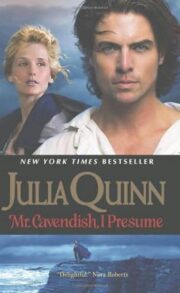

"Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" друзьям в соцсетях.