“We shall make it our mission for the autumn,” Grace suddenly announced, her eyes sparkling with intent. “Amelia and Wyndham shall finally become acquainted.”

“Grace, don’t, please…” Amelia said, flushing. Good Lord, how mortifying. To be a project.

“You are going to have to get to know him eventually,” Elizabeth said.

“Not really,” was Amelia’s wry reply. “How many rooms are there at Belgrave? Two hundred?”

“Seventy-three,” Grace murmured.

“I could go weeks without seeing him,” Amelia responded. “Years.”

“Now you’re just being silly,” her sister said. “Why don’t you come with me to Belgrave tomorrow? I devised an excuse about Mama needing to return some of the dowager’s books so that I might visit with Grace.”

Grace turned to Elizabeth with mild surprise. “Did your mother borrow books from the dowager?”

“She did, actually,” Elizabeth replied, then added demurely, “at my request.”

Amelia raised her brows. “Mother is not much of a reader.”

“I couldn’t very well borrow a pianoforte,” Elizabeth retorted.

It was Amelia’s opinion that their mother wasn’t much of a musician, either, but there seemed little reason to point it out, and besides, the conversation had been brought to an abrupt halt.

He had arrived.

Amelia might have had her back to the door, but she knew precisely the moment Thomas Cavendish walked into the assembly hall, because, drat it all, she had done this before.

Now was the hush.

And now-she counted to five; she’d long since learned that dukes required more than the average three seconds of hush-were the whispers.

And now Elizabeth was jabbing her in the ribs, as if she needed the alert.

And now-oh, she could see it all in her head-the crowds were doing their Red Sea imitation, and here strode the duke, his shoulders broad, his steps purposeful and proud, and here he was, almost, almost, almost-

“Lady Amelia.”

She composed her face. She turned around. “Your grace,” she said, with the blank smile she knew was required of her.

He took her hand and kissed it. “You look lovely this evening.”

He said that every time.

Amelia murmured her thanks and then waited patiently while he complimented her sister, then said to Grace, “I see my grandmother has allowed you out of her clutches for the evening.”

“Yes,” Grace said with a happy sigh, “isn’t it lovely?”

He smiled, and Amelia noted it was not the same sort of public-face smile he gave her. It was, she realized, a smile of friendship.

“You are nothing less than a saint, Miss Eversleigh,” he said.

Amelia looked to the duke, and then to Grace, and wondered-What was he thinking? It was not as if Grace had any choice in the matter. If he really thought Grace was a saint, he ought to set her up with a dowry and find her a husband so she did not have to spend the rest of her life waiting hand and foot upon his grandmother.

But of course she did not say that. Because no one said such things to a duke.

“Grace tells us that you plan to rusticate in the country for several months,” Elizabeth said.

Amelia wanted to kick her. The implication had to be that if he had time to remain in the country, he must have time to finally marry her sister.

And indeed, the duke’s eyes held a vaguely ironic expression as he murmured, “I do.”

“I shall be quite busy until November at the earliest,” Amelia blurted out, because it was suddenly imperative that he realize that she was not spending her days sitting by her window, pecking at needlework as she pined for his arrival.

“Shall you?” he murmured.

She straightened her shoulders. “I shall.”

His eyes, which were a rather legendary shade of blue, narrowed a bit. In humor, not in anger, which was probably all the worse. He was laughing at her. Amelia did not know why it had taken her so long to realize this. All these years she’d thought he was merely ignoring her-

Oh, dear Lord.

“Lady Amelia,” he said, the slight nod of his head as much of a bow as he must have felt compelled to make, “would you do me the honor of a dance?”

Elizabeth and Grace turned to her, both of them smiling serenely with expectation. They had played out this scene before, all of them. And they all knew how it was meant to unfold.

Especially Amelia.

“No,” she said, before she could think the better of it.

He blinked. “No?”

“No, thank you, I should say.” And she smiled prettily, because she did like to be polite.

He looked stunned. “You don’t wish to dance?”

“Not tonight, I don’t think, no.” Amelia stole a glance at her sister and Grace. They looked aghast.

Amelia felt wonderful.

She felt like herself, which was something she was never allowed to feel in his presence. Or in the anticipation of his presence. Or the aftermath.

It was always about him. Wyndham this and Wyndham that, and oh how lucky she was to have snagged the most handsome duke in the land without even having to lift a finger.

The one time she allowed her rather dry humor to rise to the fore, and said, “Well, of course I had to lift my little baby rattle,” she’d been rewarded with two blank stares and one mutter of “ungrateful chit.”

That had been Jacinda Lennox’s mother, three weeks before Jacinda had received her shower of marriage proposals.

So Amelia generally kept her mouth shut and did what was expected of her. But now…

Well, this wasn’t London, and her mother wasn’t watching, and she was just so sick of the way he kept her on a leash. Really, she could have found someone else by now. She could have had fun. She could have kissed a man.

Oh, very well, not that. She wasn’t an idiot, and she did value her reputation. But she might have imagined it, which she’d certainly never bothered to do before.

And then, because she had no idea when she might feel so reckless again, she smiled up at her future husband and said, “But you should dance, if you wish it. I’m sure there are many ladies who would be happy to partner you.”

“But I wish to dance with you,” he ground out.

“Perhaps another time,” Amelia said. She gave him her sunniest smile. “Ta!”

And she walked away.

She walked away.

She wanted to skip. In fact, she did. But only once she’d turned the corner.

Thomas Cavendish liked to think himself a reasonable man, especially since his lofty position as the seventh Duke of Wyndham would have allowed him any number of unreasonable demands. He could have gone stark raving mad, dressed all in pink, and declared the world a triangle, and the ton would still have bowed and scraped and hung on his every word.

His own father, the sixth Duke of Wyndham, had not gone stark raving mad, nor had he dressed all in pink or declared the world a triangle, but he had certainly been a most unreasonable man. It was for that reason that Thomas most prided himself upon the evenness of his temper, the sanctity of his word, and, although he did not choose to reveal this side of his personality to many, his ability to find humor in the absurd.

And this was definitely absurd.

But as news of Lady Amelia’s departure from the assembly spread through the hall, and head after head swiveled in his direction, Thomas began to realize that the line between humor and fury was not so very much more substantial than the edge of a knife.

And twice as sharp.

Lady Elizabeth was gazing upon him with a fair dose of horror, as if he might turn into an ogre and tear someone from limb to limb. And Grace-drat the little minx-looked as if she might burst out laughing at any moment.

“Don’t,” he warned her.

She complied, but barely, so he turned to Lady Elizabeth and asked, “Shall I fetch her?”

She stared at him mutely.

“Your sister,” he clarified.

Still nothing. Good Lord, were they even educating females these days?

“The Lady Amelia,” he said, with extra enunciation. “My affianced bride. The one who just gave me the cut direct.”

“I wouldn’t call it direct,” Elizabeth finally choked out.

He stared at her for a moment longer than was comfortable (for her; he was perfectly at ease with it), then turned to Grace, who was, he had long since realized, one of the only people in the world upon whom he might rely for complete honesty.

“Shall I fetch her?”

“Oh, yes,” she said, her eyes shining with mischief. “Do.”

His brows rose a fraction of an inch as he pondered where the dratted female might have gone off to. She couldn’t actually leave the assembly; the front doors spilled right onto the main street in Stamford-certainly not an appropriate spot for an unescorted female. In the back there was a small garden. Thomas had never had occasion to inspect it personally, but he was told that many a marriage had been proposed in its leafy confines.

Proposed being something of a euphemism. Most proposals occurred in a rather more complete state of attire than those that came about in the back garden of the Lincolnshire Dance and Assembly Hall.

But Thomas didn’t much worry about being caught alone with Lady Amelia Willoughby. He was already shackled to the chit, wasn’t he? And he could not put off the wedding very much longer. He had informed her parents that they would wait until she was one-and-twenty, and surely she had to reach that age soon.

If she hadn’t already.

“My options appear to be thus,” he murmured. “I could fetch my lovely betrothed, drag her back for a dance, and demonstrate to the assembled multitudes that I have her clearly under my thumb.”

Grace stared at him with amusement. Elizabeth looked somewhat green.

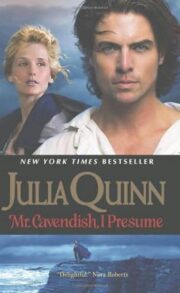

"Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" друзьям в соцсетях.