“I am sure you were thinking as I was,” she continued, “that we could simply take the carriage out to the country and while away an hour or two before returning me home.”

He was, actually. It would be hell on her reputation, were they discovered, but somehow that seemed the least of his concerns.

“But you don’t know my mother,” she added. “Not as I do. She will send someone to Belgrave. Or perhaps come herself, under some guise or another. Probably something about borrowing more books from your grandmother. If she arrives, and I am not there, it will be a disaster.”

He almost laughed. The only reason he did not was that it would be the height of insult, and there were certain gentlemanly traits he could not abandon, even when the world was falling down around him.

But really, after the events of yesterday-his new cousin, the possible loss of his title, his home, probably even the clothes on his back-the ramifications of an illicit country picnic seemed trivial. What could possibly happen? Someone would see them and they would be forced to marry? They were already betrothed.

Or were they? He no longer knew.

“I know that it would only hasten a ceremony that has been preordained for decades, but”-here her voice became tremulous, and it pierced his heart with guilt-“you don’t want that. Not yet. You’ve made that clear.”

“That’s not true,” he said quickly. And it wasn’t. But it had been. And they both knew it. Looking at her now, her blond hair shining in the morning light, her eyes, not so hazel today, this time almost green-he no longer knew why he’d put this off for so long.

“I don’t want it,” she said, her voice almost low enough to be a whisper. “Not like that. Not some hastily patched-up thing. Already no one thinks you really want to marry me.”

He wanted to contradict her, to tell her she was being foolish, and silly, and imagining things that were simply not true. But he could not. He had not treated her badly, but nor had he treated her well.

He found himself looking at her, at her face, and it was as if he’d never truly seen her before. She was lovely. In every way. And she could have been his wife by now.

But the world was a very different place than it had been this time yesterday, and he no longer knew if he had any right to her. And good Lord, the last thing he wished to do was take her to Belgrave. Wouldn’t that be fun? He could introduce her to Highwayman Jack! He could imagine the conversation already.

Amelia, do meet my cousin.

Your cousin?

Indeed. He might be the duke.

Then who are you?

Excellent question.

Not to mention the other excellent questions she was sure to come up with, most notably-what, exactly, was the state of their betrothal?

Good God. The mind boggled, and his mind, on the mend but still worse for the wear after a night of drink, preferred to remain boggle-free.

It would be so easy to insist that they not go to Belgrave. He was used to making the decisions, and she was used to having to abide by them. His overriding of her wishes would not seem at all out of character.

But he couldn’t do it. Not today.

Maybe her mother would not seek her out. Maybe no one would ever know that she’d not been where she said she’d be.

But Amelia would know. She would know that she had looked him in the eye and told him why she needed to go to Belgrave, and she would know that he had been too callous to consider her feelings.

And he would know that he’d hurt her.

“Very well,” he said brusquely. “We shall head to Belgrave.” It wasn’t exactly a cottage. Surely they could avoid Mr. Audley. He was probably still abed, anyway. He didn’t seem the sort to enjoy the morningtide.

Thomas directed the driver to take him home and then climbed into the carriage beside Amelia. “I don’t imagine you are eager for my grandmother’s company,” he said.

“Not overmuch, no.”

“She favors the rooms at the front of the castle.” And if Mr. Audley was indeed awake, that was where he would also be, probably counting the silver or estimating the worth of the collection of Canalettos in the north vestibule.

Thomas turned to Amelia. “We shall enter at the back.”

She nodded, and it was done.

When they reached Belgrave, the driver made straight for the stables, presumably, Amelia thought, on the duke’s orders. Indeed, they reached their destination without ever coming within sight of the castle’s front windows. If the dowager was where Wyndham had said she would be-and indeed, in all her visits to the castle, Amelia had only ever seen the dowager in three separate rooms, all at the front-then they would be able to carry out the rest of the morning in relative peace.

“I don’t believe I’ve ever been ’round to this side of Belgrave,” Amelia commented as they entered through a set of French doors. She almost felt like a thief, sneaking about as she was. Belgrave was so still and quiet over here at the back. It made one aware of every noise, every footfall.

“I’m rarely in this section,” Thomas commented.

“I can’t imagine why not.” She looked about her. They had entered a long, wide hall, off which stood a row of rooms. The one before her was some sort of study, with a wall of books, all leather-bound and smelling like knowledge. “It’s lovely. So quiet and peaceful. These rooms must receive the morning sun.”

“Are you one of those industrious sorts, always rising at dawn, Lady Amelia?”

He sounded so formal. Perhaps it was because they were back at Belgrave, where everything was formal. She wondered if it was difficult to speak guilelessly here, with so much splendor staring down upon one. Burges Park was also quite grand-there was no pretending otherwise-but it held a certain warmth that was lacking at Belgrave.

Or perhaps it was just that she knew Burges. She’d grown up there, laughed there, chased her sisters and teased her mother. Burges was a home, Belgrave more of a museum.

How brave Grace must be, to wake up here every morning.

“Lady Amelia,” came Thomas’s reminding voice.

“Yes,” she said abruptly, recalling that she was meant to answer his question. “Yes, I am. I cannot sleep when it is light out. Summers are particularly difficult.”

“And winters are easy?” He sounded amused.

“Not at all. They’re even worse. I sleep far too much. I suppose I should be living at the equator, with a perfect division of day and night, every day of the year.”

He looked at her curiously. “Do you enjoy the study of geography?”

“I do.” Amelia wandered into the study, idly running her fingers along the books. She liked the way the spine of each volume bowed slightly out, allowing her fingers to bump along as she made her way into the room. “Or I should say I would. I am not very accomplished. It was not considered an important subject by our governess. Nor by our parents, I suppose.”

“Really?”

He sounded interested. This surprised her. For all their recent rapprochement, he was still…well…him, and she was not used to his taking an interest in her thoughts and desires.

“Dancing,” she replied, because surely that would answer his unspoken question. “Drawing, pianoforte, maths enough so that we can add up the cost of a fancy dress ensemble.”

He smiled at that. “Are they costly?”

She tossed a coquettish look over her shoulder. “Oh, dreadfully so. I shall bleed you dry if we host more than two masquerades per year.”

He regarded her for a moment, his expression almost wry, and then he motioned to a bank of shelves on the far side of the room. “The atlases are over there, should you wish to indulge your interests.”

She smiled at him, a bit surprised at his gesture. And then, feeling unaccountably pleased, she crossed the room. “I thought you did not come to this section of the house very often.”

He quirked a dry half smile, which somehow sat at odds with his blackened eye. “Often enough to know where to find an atlas.”

She nodded, pulling a tall, thin tome at random from the shelf. She looked down at the gold lettering on the cover. MAPS OF THE WORLD. The spine creaked as she cracked it open. The date on the title page was 1796. She wondered when the book had last been opened.

“Grace is fond of atlases,” she said, the thought popping into her head, seemingly from nowhere.

“Is she?”

She heard his steps drawing near. “Yes. I seem to recall her saying so at some point. Or perhaps it was Elizabeth who told me. They have always been very good friends.” Amelia turned another page, her fingers careful. The book was not particularly delicate, but something about it inspired reverence and care. Looking down, she saw a large, rectangular map, crossing the length of both pages, with the caption: Mercator projection of our world, the Year of our Lord, 1791.

Amelia touched the map, her fingers trailing softly across Asia and then down, to the southernmost tip of Africa. “Look how big it is,” she murmured, mostly to herself.

“The world?” he said, and she heard the smile in his voice.

“Yes,” she murmured.

Thomas stood next to her, and one of his fingers found Britain on the map. “Look how small we are,” he said.

“It does seem odd, doesn’t it?” she remarked, trying not to notice that he was standing so close that she could feel the heat emanating from his body. “I am always amazed at how far it is to London, and yet here”-she motioned to the map-“it’s nothing.”

“Not nothing.” He measured the distance with his smallest finger. “Half a fingernail, at least.”

She smiled. At the book, not at him, which was a much less unsettling endeavor. “The world, measured in fingernails. It would be an interesting study.”

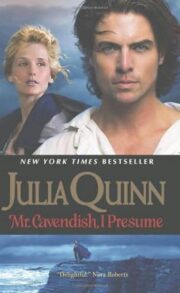

"Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Cavendish, I Presume" друзьям в соцсетях.