You would think a psychic would have a little warning about these things.

But then, that’s what sucks about being me: I’m not a psychic anymore.

Two

“Jess,” Rob said, looking past me into the living room, where Skip and Mike were sprawled across the couch like a couple of beached tunas. “Is this a bad time?”

Jess, is this a bad time?

That is what my ex-boyfriend says to me after what turned out to be two years or so of radio silence. Not so much as a phone call.

And okay, yeah, I’m the one who went to Afghanistan. I will admit that.

But need I remind you that it was TO HELP FIGHT A WAR?

It wasn’t like I was out there HAVING FUN.

Not like HE was having, the entire time I was gone. Or so I can only assume, since when I got back, I found him in a liplock with some bleached blonde in a tube top outside of his uncle’s garage.

Oh, sure. He said SHE’D kissed him. For fixing her carburetor. He said if I had stuck around, instead of just taking off like a coward and running, I’d have seen him tell her off.

Yeah. I bet. Because guys just so hate it when blondes in platform heels with spray-on tans and boobs bigger than my head lean over and plant big wet ones on them.

Whatever. It wasn’t like things had been going so great with him before I’d left for Washington and points east. My mom had not been, shall we say, thrilled by the fact that her then not-yet seventeen-year-old daughter was dating a guy who had not only already graduated from high school, but was

a) not going to college.

b) working as a mechanic in his uncle’s garage.

c) from the “wrong side of the tracks,” or, in the local vernacular, a “Grit.”

d) on probation for a crime, the nature of which he would never reveal.

She didn’t exactly make it easy on the two of us. The first (and only) night Rob came over for dinner, she pointed out to him how in the great state of Indiana, it is considered statutory rape if a person eighteen years of age or older engages in sexual intercourse with a person sixteen years of age or younger, a crime punishable by a fixed term of ten years with up to ten years added or four subtracted for aggravating and mitigating circumstances.

It didn’t matter how many times I insisted that Rob and I were not engaging in sexual intercourse (much to my everlasting regret and sorrow). Mom just had to say the words “statutory rape” and Rob was gone, with a promise he’d be back when I turned eighteen.

I never even got to go to his uncle’s wedding with him, the one he’d promised to take me to.

And then the war came.

And when I came back, having turned eighteen and lost the one ability I’d had that set me apart from all the other girls in town (besides my refusal to grow my hair out), I found him with Miss Thanks-for-Fixing-My-Carburetor-Here-Getta-Load-of-These-Head-Sized-Boobs.

He didn’t see me. See him with her, I mean. He only found out I was back in town because Douglas told him when he stopped by the comic shop later that day, which, according to Douglas, Rob does periodically, to pick up the latest Spider-Man (which is funny, because I didn’t even know Rob liked comic books) and shoot the breeze if Douglas is working the counter.

So Douglas told him I was home, and Rob came by my house that very afternoon, purring up on the self-same cherried-out Indian on which he’d given me that very first ride, so many years before.

He seemed pretty surprised when I told him to get the hell off my property. Even more surprised when I told him I’d seen him with the blonde.

At first I think he thought I was kidding. Then, when he saw I wasn’t, he got mad. He said I didn’t know what I was talking about. He also said the Jess he’d known wouldn’t have run away just because she saw some girl kissing him. He said the Jess he’d known would have stuck around and knocked his (not to mention the girl’s) block off.

He also said that I didn’t know what it had been like for him, with me gone and him not knowing where I was, if I was getting blown up or what (because of course it wasn’t like they’d let me call and tell people where I was, or anything like that, when I’d been overseas).

I guess it never occurred to Rob that it hadn’t been any big picnic for me, either. You’d think he might have been able to tell, what with all of the newspapers trumpeting my ignominious return home, and return to normalcy (“Spark’s Gone for Lightning Girl” and “Hero Comes Home, Psychic No Longer—Gave All to War Effort”).

I guess it never occurred to Rob that I WASN’T the Jess he’d known, the one who’d have knocked his block off. Not anymore.

I was the one who’d suggested a cooling-off period.

He was the one who said that maybe that would be a good idea.

And then I got the call from Juilliard: my spot on the wait list—I barely remembered auditioning. It had been during one of my leaves home—had come up. Classes started the very next day. Did I still want it?

Did I still want it? A chance to lose myself in music? The opportunity to get away from myself, the nightmares, the blonde with the head-sized boobs, my mother?

Did I ever.

So I left. Without saying good-bye.

And I never saw him again.

Until today.

Well, okay, that’s not quite true. I guess I should confess that I couldn’t resist forcing others (I would never do it myself, for fear that he might see me) to drive by the garage where he worked, so I, sunk low in the backseat, could try and catch a glimpse of him now and then. Like when I came home from school, at Christmas, and spring break, and stuff.

And he always looked as fine as he had that day I’d first met him, in detention, back at Ernie Pyle High—so tall and cool and…justgood . Know what I mean?

But he never called. Even when he had to know I was home, like over winter break. He certainly didn’t drive by my house in the middle of the night to see if my light was on or to throw pebbles at my window to get me to come down.

I guessed he’d moved on. And I didn’t blame him. I mean, I didn’t exactly come back from my year away…well, whole. I certainly wasn’t who I’d used to be, as he’d been only too quick to point out.

So I decided he wasn’t who he’d used to be, either. Maybe, I decided, my mom was right. Rob and I were ultimately too different to be compatible. Our backgrounds were too disparate. What Rob wants—well, I don’t know what it is that he wants, since I haven’t seen him in so long. And now that I can’t find people anymore, I don’t know what I want, either.

But I do know Rob and I can’t possibly want the same things. Because nowhere in my future do I envision a tube top.

It seems simplest just to tell myself that I want what Mom tells me I should want: a college degree, a decent career, and a nice steady guy like Skip, who’ll make a hundred thousand dollars a year someday. Skip’s a good sort of person, my mom says, for a classical musician to be married to. Because classical musicians don’t make that much money, unless they’re famous, like Yo-Yo Ma or whoever.

And the truth is, I’m too tired to try to figure out what I want. It’s just easier to decide I want what my mom wants for me.

So that’s why. About Rob, I mean. That’s why I didn’t fight for him, for what we’d once had. I didn’t try to fix it. I was just too tired.

So I moved on.

Except that now here he was, a year later, standing in my doorway. He wasn’t keeping his part of the (unspoken) bargain.

And he definitely looked whole to me. MORE than whole, in fact. He looked every bit as good as he had that day after detention, when he’d offered me that ride home. Same pale blue eyes, so light, they’re almost gray. Same tousled dark hair, a little longer in back than my mom likes guys to wear their hair. Same jeans that fit like a glove, faded in all the right (or wrong, depending on how you want to look at it) places.

Seeing him, looking that good, standing outside my door, was a lot like getting…well, struck by lightning.

A sensation with which I am not unfamiliar, actually.

“Ask him if he can break a fifty,” Skip yelled, thinking it was the pizza guy.

“Make sure he remembered the hot-pepper flakes,” Ruth called from the kitchen, where she was taking down the plates. “They forgot last time.”

I just stood there, staring at him. It had been so long since I’d stood this close to him. And everything was flooding back—the way he’d smelled (like whatever laundry detergent his mom uses, coupled with soap and, more faintly, the stuff mechanics use to get the grease out from beneath their fingernails); the way he used to kiss me…one or two light kisses, not even directly centered on my mouth all the time, then one long, hard one, dead in the middle, that made me feel as if I were exploding; the way his body had felt, pressed up against mine, so long and hard and warm….

“This is a bad time,” Rob said. “You’ve got company. I can come back later.”

“Hey, can you break this?” Skip pushed past me, waving a fifty-dollar bill. He stopped when he saw Rob wasn’t holding a pizza. “Hey, where’s the ’za?” he wanted to know. Then he looked at Rob’s face, and his eyes narrowed.

“Hey,” Skip said in a different tone of voice. “I know you.”

Ruth had poked her head out from the kitchen doorway. “Did you remember the hot-pepper—” Her voice trailed off as she, too, recognized Rob.

“Oh,” she said in a very different voice. “It’s…it’s…”

“Rob,” Rob said in that deep, no-nonsense voice that had always managed to send my pulse racing—same as, for some time now, the sound of a motorcycle engine had. It’s like those dogs we learned about in Psych. The ones who would only get fed after a bell rang? Whenever they heard a bell ring after that, they’d start drooling. Whenever I hear a motorcycle engine—or Rob’s voice—my heart speeds up. In a good way.

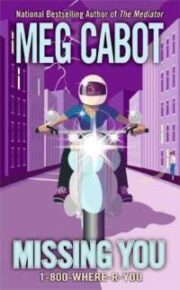

"Missing You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Missing You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Missing You" друзьям в соцсетях.