“Come on, Jess,” Douglas said from the doorway. “Every locally owned business in this town is selling out to the chains. Look what happened to the Chocolate Moose.”

“Not every locally owned business is selling out to the chains, Douglas,” my dad pointed out dryly, meaning the restaurants we still owned.

“Do you really want to see the place where you played the mouse inThe Lion and the Mouse in your third grade program turned into condos?” Douglas asked me, ignoring our father.

Well, it wasn’t as if I’d had any better offers. No one else had asked me to do anything with them that evening. And if I stayed home, Mom would just put me on dish patrol.

I was touched Douglas even remembered that I’d played the mouse in my third grade program.

“I’ll go,” I said, and stood up to follow Douglas and his girlfriend.

They spent the three-block walk over to the elementary school filling me in on their proposal to turn Pine Heights into a high school—“An alternative high school,” Douglas said. “Not like Ernie Pyle, which was so big and impersonal. That place…it was like an education factory,” he added with a shudder.

Which was interesting, because I hadn’t seen a whole lot of educating going on there.

“The alternative high school would put an emphasis on kids working at their own pace,” Tasha, who was an education major over at IU, said.

“Yeah,” Douglas said. “And instead of the standardized state curriculum, we’re going to have an emphasis on the arts—music, drawing, sculpture, drama, dance. And no sports.”

“No sports,” Tasha said firmly, and I remembered that her brother had been a football player…and how much attention he’d gotten because of it, whereas she, a shy and studious girl, had been almost the family afterthought.

“Wow,” I said. “Great.”

I meant it, too. I mean, if I had gone to a school like the one they were describing, instead of the one I’d gone to, maybe I wouldn’t have turned out the way I had—broken. I definitely wouldn’t have been struck by lightning. That happened to me walking home from Ernie Pyle High. If I’d have been walking home from Pine Heights, which was so close to my house, I’d have made it home well before the rain started to fall.

It was weird being back inside my elementary school after all these years. Everything looked tiny. I mean, the drinking fountains, which I remembered as being so high off the ground, were practically knee-level.

It still smelled the same, though, of floor wax and that stuff they sprinkle over throw-up.

“Remember that time you banged Tom Boyes’s head into that water fountain, Jess?” Douglas asked cheerfully, as we walked by an otherwise unremarkable drinking fountain. “For calling me—what was it? Oh, yeah. A spastic freak.”

I didn’t remember this. But I can’t say I was surprised to hear it.

Tasha, on the other hand, seemed so.

“Why did he call you that?” she wanted to know. “Just because you were different?”

Different. That was one way to put it. Douglas always HAD been different. If you could call hearing voices inside of your head telling you to do weird stuff, like not eat the spaghetti in the school cafeteria because it was poisoned, different.

“Yeah,” Douglas said. “But it was all right, because I had Jessica to protect me. Even though I was in fifth grade, and she was in first. God, Tom couldn’t hold his head up all year after that. The snot beat out of him by a tiny first grade girl.”

Tasha smiled at me admiringly, but I know there was nothing all that admirable about that situation. My high school counselor and I had worked long and hard to combat my seemingly uncontrollable temper, which was always getting me in hot water. I’d finally succeeded in getting control of it, but only after seeing for myself firsthand what could happen when someone with a bad temper got too much power—such as some of the men I’d helped catch in Afghanistan.

We walked into the school’s combination auditorium, complete with stage, gym (basketball hoops), and cafeteria (long tables that folded up into the walls to get them out of the way during PE or Assembly). The room seemed ridiculously small compared to the way I remembered it. About ten rows of folding chairs had been set up before a long table, on top of which sat a scale model of Pine Heights school, only with the windows and landscaping redone, so it looked more like an upscale condo complex than a school.

Standing behind this model, glad-handing what had to be a bunch of city planners and local politicians, was a pot-bellied businessman in an expensive new suit…which couldn’t have been all that comfortable in the summer heat, considering the school had no air-conditioning.

And standing next to the beer-bellied man was another guy in a suit, although this one was more appropriate for the weather, being silk. Also, the guy in it wore the jacket over a black T-shirt instead of a button-down and tie.

Except for the change of clothes, though, he was still perfectly recognizable as someone I had seen—albeit from a distance—just a few hours before.

Hannah’s boyfriend, the two-timing Randy.

Ten

“Everyone, if you could take your seats, please.”

The city councilperson called everyone who was milling around, greeting one another—including my suddenly civic-minded brother—to order. We took our seats and sat there in the evening heat, some people fanning themselves with handouts Randy’s dad had left on all our seats. The handouts described the complex he wanted to convert Pine Heights school into—a brand-new luxury condo “experience,” with a gym and a coffee shop on the first floor. Apparently, more and more DINKs—double income, no kids—were moving to our town, commuting from it to Indianapolis. Such a condo “experience” would perfectly suit their needs.

People stood up and started talking, but the truth was, I didn’t hear a word they said. I wasn’t listening. Instead, I was staring at Randy Whitehead.

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised. I mean, we live in a pretty small town. If a guy’s dad owns one apartment complex, chances are he’s going to own more than one. I mean, look at my dad. He owned not one, but three of the most popular restaurants in a town barely large enough to support a single McDonald’s.

Still, it was a shock to see Randy, up close and personal. He seemed to be there strictly in a “supportive son” role, not saying much, and handing his dad things when it was Mr. Whitehead’s turn to make his presentation. There was no denying that the guy was hot. Randy, I mean. If you like the hundred-dollar-haircut, loafers-without-socks type. Which I guess, to an inexperienced girl like Hannah, would seem pretty exotic.

To me, though, he looked like he would smell. Not of BO. But of too much cologne. I hate it when guys smell of anything but soap. Randy Whitehead looked as if he were DRIPPING in Calvin Klein For Men.

“The overall cost of each of these units,” Mr. Whitehead was saying, “would be in keeping with the rising cost of real estate in a town that is fast becoming an extremely sought-after bedroom community for upwardly mobile workers in nearby Indianapolis. We’re talking low to mid six figures, depending on the type of amenities buyers choose to incorporate into the overall design plan they select. In no way will the Pine Heights community suffer an influx of undesirably lower-income residents through this conversion.”

Randy, while his father spoke, softly tapped a pencil. He didn’t look like a man wondering where his soul mate had vanished to earlier in the day. He looked like a man who wanted to go home to watch some HBO and have a Heineken or two.

The community listened politely to Mr. Whitehead’s spiel, asking one or two questions pertaining to parking and the school’s baseball field, which was still utilized on a somewhat sporadic basis by families who enjoyed an impromptu game of softball on a summer evening. The baseball field would go, turned into a “lush green park area, open to the public, complete with a duck pond.” This, in turn, led to questions about mosquitoes and West Nile virus.

What, I asked myself, was I still doing here? In Indiana, I mean. I had done what Rob had asked me to do. Why wasn’t I on a plane back to New York by now? That’s where my life was these days. Not here, listening to people freak out about a baseball field.

Of course, back in New York, I never really felt as if I belonged, either. I mean, everyone in New York was so excited about going to Broadway shows and having picnics in Central Park. Everyone but me.

Maybe the problem wasn’t Indiana or New York. Maybe the problem was me. Maybe I wasn’t capable of happiness anymore. Maybe Rob was right, and I was broken. Permanently broken, and would never find happiness again—

My musings on my seemingly permanent state of not caring about anything were interrupted by, of all people, my brother Douglas as he stood up and said, “I’d like to know how far the city council has gotten on its review of our proposal for Pine Heights to be turned into an alternative high school.”

There was considerable murmuring about this. But not because people thought it was so out there or weird, as people have murmured over things my brother’s said in the past. There was a general note of approval in this murmur. Someone at the far side of the gym shouted, “Yeah!” while someone on the other side said, “We don’t want teenagers roaming around loose in our neighborhood.”

“Alternative doesn’t mean unsupervised,” Douglas was quick to point out. “State certification will be required of teachers wishing to apply to work at Pine Heights Alternative High School. And like any school, loitering on school grounds after hours will not be permitted.”

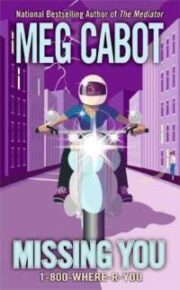

"Missing You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Missing You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Missing You" друзьям в соцсетях.