Klavdia had had the misfortune of falling in love with revolutionaries. This she confided to Margarita and counseled her against. In 1905, at the age of twenty, she met and eloped with her first revolutionary husband and her middle-class Muscovite family disowned her. A year later when the Tsar responded with a provisional constitution and their forbidden love had cooled, they separated and divorced. In 1917, she had married her second, a Trotskyite, who was subsequently arrested. Life had been hard for her, she told them. She preferred to speak in generalities. She would press Margarita for information about her liaisons then shake her head. She linked her own sad fortunes to men, and by extension, the sad fortunes of all women. Anyuta observed that she asked a lot of questions.

That evening when the others returned from the work site, Raisa’s bed board had been cleared and her belongings removed. A guard volunteered that she’d been taken to the infirmary. Speculation circulated about a possible contagion. Later, during dinner, another guard reported that she’d died in the afternoon and conversations were reduced to whispers. Klavdia sat next to Margarita. At the news, she set down her fork and stared at her food with new dismay. This seemed an aspect to her sentence she’d not anticipated. She leaned in toward Margarita and whispered.

“Did you know her?”

Anyuta watched from across the table. “What does that matter?” she said.

Klavdia sat back.

“Did you ever find your sweaters?” asked Anyuta sweetly. Others along the bench looked over.

Klavdia shook her head.

“That’s too bad,” said Anyuta. “It gets cold when they run out of fuel.” She banged her teeth together in an exaggerated chatter.

Someone suggested they hold a short service for the dead woman. Others agreed. Anyuta went on eating.

Margarita watched her and her misery grew. Oh Raisa! Poor Raisa.

“How has it been at the work site?” Margarita asked her.

“Why? Did you miss us?” Anyuta laughed harshly then stabbed at something on her plate.

The next morning the bus stopped across the street from the Party Headquarters and idled. Margarita was beside Anyuta as always. Klavdia was across the aisle. This morning Anyuta had been as chatty as ever. A story about a dog and a rabbit. Her hand and empty sleeve moved in unison as she animated some provincial barnyard stand-down. The guard spoke briefly with the driver, then turned to face the prisoners. Margarita put her hand on the sleeve. She felt the stump beneath the cloth. Anyuta stopped talking.

The guard announced that an accountant was needed. A replacement for Raisa, though this was not explicit. He made eye contact with no one. Was there one among them with adequate experience? Nearly everyone raised their hands. He started down the aisle. Anyuta grabbed his coat and he stopped.

“Pick me, Comrade,” she said gaily. “You need a ‘counter?’ I can make it to a hundred on most days.”

His empty face filled with humor. “You?” he began. “We all know your talents.” He glanced at Margarita as though suddenly embarrassed and remembered his mission.

“You,” he said to her. “You have sufficient training?”

Margarita sensed calculation in her every move. She could not appear too eager, too intelligent, too conniving, too fearful. Too memorable. She watched him measure her. Perhaps he recalled the fainting episode a few days earlier. Perhaps not entirely, but somehow, choosing her would make sense to him. Perhaps because she was close to the front of the bus; because she could save him a few steps, a few more encounters; those simple truths were in her favor.

She shrugged a little. “Yes, Comrade. I have some experience.” She tried to keep all expression from her face.

From the other side of the aisle, Klavdia spoke. “It should be me,” she said, her voice rising as she saw opportunity slip from her. “It was my job, my work, before—I should be the one.” The guard ignored her. She was too new.

He stood back to let Margarita pass from the seat. Audible protests echoed from the back of the bus.

Margarita felt a light push against the small of her back. It was the stump. She turned and saw Anyuta’s shining face. Margarita touched the sleeve again, then followed the guard.

As she descended the stairs she caught Klavdia’s expression: fear and disappointment, and a modest measure of resentment. Margarita would later speak to Anyuta. She’d ask her to look after the older woman at the work sites, help her navigate the prison world. Anyuta wouldn’t want to. Why her, she’d say. Because she’s new, Margarita would tell her. Because she needs your help. Finally, Just do it for me. Anyuta would make a face in the older woman’s direction. She smells funny, she’d say. Margarita would laugh at this. No different from the rest of us.

Margarita followed the guard across the slushy roadway. There was a broad square of yard covered evenly with snow in front of a flat-faced building. The sign indicated that within were produced the materials for shoes for the betterment of Soviet women.

She took this as a message from the universe to her specifically.

CHAPTER 32

Pyotrovich arrived in Irkutsk several weeks after Bulgakov. He seemed annoyed that Bulgakov had learned nothing of Ilya’s plans. When Bulgakov demanded to see Margarita, Pyotrovich suggested he make the request through typical channels.

“That will take too long,” said Bulgakov.

“In the provinces, people find they are happy with time,” said Pyotrovich.

Bulgakov did as he suggested; his letters went unanswered as did Pyotrovich’s promises to investigate the matter.

Pyotrovich had made the arrangements for Bulgakov’s apartment. It was the larger part of the ground floor of a house; in the rear there was a small garden with a metal bench and a koi pond, though at the present it lay snowy and undisturbed. His neighbors were notable for their friendliness and lack of curiosity about him. One evening he was invited to supper by the couple who lived upstairs; he’d knocked, inquiring about the location of the library in town, and had commented favorably on the aroma of the stew the wife had prepared. Conversation was warm, though limited to the weather and local current events. She had the hint of a foreign accent. Bulgakov told them he was a writer; there was a fleeting expression of concern on the man’s face but it quickly disappeared, and the subsequent conversation was about the latest upgrades that had been approved and initiated on the town’s supply of drinking water. After he’d departed, he heard their voices for hours through the ceiling of his bedroom. From the next morning onward, though, it was so quiet he might have been the only occupant of the building.

He had brought the novel manuscript with him; it’d been neglected for months and at first it seemed to resist his revisiting of its scenes. He approached it with great discipline; the isolation allowed for this. He wrote from midmorning each day until the waning light of afternoon at which time he would prepare tea and a light meal. The rest of the evening he would read. Saturday mornings and Wednesday afternoons he would visit the library as well as replenish his supplies. Occasionally he would knock on the door of the couple above to inquire if they needed anything but there was never a response and he was given to imagining that they’d been spirited away in the night by demons or the secret police, though the truth was more likely that they’d decided to finish the winter in warmer climes. Whatever the reason, his present aloneness transformed itself into loneliness and he found that he would watch the meanderings of falling snow from his window, attributing its varying uplifts and descents with vague notions of hope and despair.

One Saturday morning after nearly a month, he heard the faint tapping of footsteps above him. It was past the time he would have typically left on his errands. Could it be mice? The sounds, though soft, were discrete and he rose from his chair to go to the door. Was it an intruder? The sounds immediately stopped and he waited. Had he imagined it? He went upstairs and tapped on the door.

The hallway was dim and chilled and he pulled his jacket across his chest. There was no answer. He tapped again, then turned to leave. The door opened slightly. He saw only part of the woman’s face before it started to close again.

“Wait,” he said. He put up his hand to keep the door from closing. “I thought you’d gone. Both of you.”

She opened the door more fully. Her hair was covered in a large kerchief. A momentary expression of guilt crossed her face, then she recovered. “My husband says writers need quiet. We were hoping not to disturb you.”

“May I come in?” said Bulgakov. He looked past her hopefully.

The door did not move. “Saturday mornings I clean,” she said. She held a cloth in her hand.

“No doubt this is why I thought you were traveling,” said Bulgakov. “I’m typically out, otherwise I would have heard you.”

She smiled slightly at his conclusion.

“Oh—I have something for you,” he said. “I’ll be right back—don’t go.” He laughed aloud at the absurdity of his speech; did he think she would vanish the moment he turned his back? He returned with a small stack of letters. She was waiting as promised.

“These were delivered to me in error,” he said.

She took the mail. “It was at one time our apartment,” she said. It was her enunciation of “our” that caught him. The door had opened wider; the light from the interior showed the careworn lines of her face; she was quite a bit older than he’d thought.

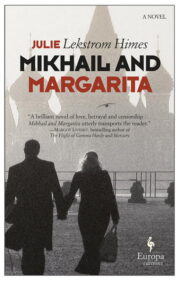

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.