CHAPTER 30

In the summer of 1826, Prince Sergei Volkonsky and the other Decembrists walked six thousand kilometers from St. Petersburg to the silver mines of Nerchinsk, a penal colony near the Russian-Chinese border. One foot of each man was shackled to the same-such foot of the prisoner preceding; the alternate foot was chained to one in the rear of him. Thusly, in lockstep, they came to know each weedy hillock, each crusted rut of the road that was Levitan’s Vladimirka. The Russian steppe extended an indecipherable distance in all directions until it met with the towering sky. There it formed an encircling seam of which they were forever captive, low and at its center. After the second week, they rarely looked beyond the edge of the road and when they did, it only served to renew their utter despair for the years that remained of their still young lives. There could be no better prison, said Volkonsky to his friend, Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, chained to his rear. No stone wall could so completely extract all hope from a man’s breast. Trubetskoy did not respond. The failure of their revolt, their failure to wrest from the Tsar even those most modest concessions for representational governance no longer caused him to wonder. Indeed, how could the Tsar, no different from any Russian, understand freedom, trapped in a land that went on forever yet never changed?

Ilya said nothing when Bulgakov first opened the door of their shared compartment. He’d been reading the paper; it came to rest in his lap as Bulgakov struggled to enter with his luggage. It seemed to Bulgakov that he himself was the more surprised. He consulted his ticket. He was in the correct berth. How was he to explain this cosmic alignment?

“This isn’t entirely coincidental,” said Bulgakov. He shut the compartment door. “When you told me of her destination, I immediately requested relocation to a nearby town.”

“Have you been to Irkutsk in January? You may rethink your fortune.” Ilya resumed his reading. He seemed too accepting of this happenstance and while he may have found Bulgakov’s explanation absurdly thin, he did not appear to consider him a threat.

The compartment was small and clean, though there was a musty odor. Its walls were paneled in honey-colored wood. Two benches faced each other with a short table between. The longer of the two would serve as a bed; above it, a narrow door concealed a second berth which could be prepared as well. The window was hung in velvet drapes; beyond, a wintry Moscow rushed by. The train jerked suddenly and Bulgakov reached for the wall beside him.

If Pyotrovich could detain Bulgakov on the platform, why would he let Ilya proceed? “Aren’t you afraid of being caught?” Bulgakov asked. He’d lowered his voice.

Ilya paused before answering. “There is no crime in riding a train.”

Pyotrovich would want to catch him in the act, convict him of the greater crime.

“I’m visiting my brother,” said Ilya.

“I wouldn’t have guessed you had a brother.”

“He would likewise be surprised.” Ilya shook his head at the page as though amused. “It seems a company of workers, led by an up-and-coming Stakhanovite, worked for days on end to surpass all timelines for the laying of pipes between a reservoir and their town’s cisterns. Unfortunately, they connected the lines to a sewage tank. Thousands were sickened.”

“There may be opportunities to visit her,” said Bulgakov. “I’ve heard such can be true.”

“I’m surprised this was published,” said Ilya, frowning at the byline. “Stupidity is not generally a problem here. Ah—of course—he was revealed as an enemy of the People. Wreckers we have by the thousands, idiots nary a one.”

“I’m willing to wait for her,” said Bulgakov.

With this declaration, Ilya reassessed him. His expression seemed something akin to sympathy. He raised the page again, as though to hide it.

“I can ask the porter about moving to a different compartment,” said Bulgakov.

“There is no need,” said Ilya.

Bulgakov recognized the suitcase on the rack above; the one with the hidden compartment. It seemed then there were three of them traveling together: two men and their shared purpose. The newspaper fluttered slightly. After a while, there came the sound of snoring.

Beyond the outskirts of Moscow there were provincial towns. Beyond these were villages strung along the rails, some with only a handful of unpainted huts. Occasionally and in a seemingly arbitrary manner, the train would stop and allow its passengers to disembark. Older folk, women mainly, clad in layers of shapeless black cloth, waited on the platform with baskets of prepared foods at their feet. Bulgakov tried to engage them with simple questions, of their livelihood, their families. They answered by indicating with their fingers the number of coins required for a sampling of food. As if it was inconceivable they might share the same language of the travelers. Bulgakov wondered of the content of their days when the rails were quiet. They wouldn’t wonder of him, he knew, as though, like his language, his life was impossible to comprehend. After a day even such scraps of civilization were gone and there was only hour after hour of empty steppe.

It was difficult to focus one’s thoughts in this landscape. Bulgakov tried to imagine the future with no more ambition than to conceive of an upcoming meal and found this nearly impossible. Thoughts drifted into the undergrowth of the past. He ruminated on his first clinical appointment in the year following medical university, assigned to a village that offered little more than those they’d passed. He could remember none of his successes, only those who had succumbed in spite of his efforts. He might say their spirits visited him, but in truth, he was the ghost who went to their bedsides, interrogating those moments of indecision and exhaustion, of gross ignorance and utter inexperience. He was young then. He knew better now of grief. He was sorry then, but perhaps not sorrowful. That was his sin and he returned to it again and again.

The drone of the rails was unending. Vibrations from the churning wheels gave even fixtures of steel and wood the look of animation. Beyond their window, the interminable expanse of crumpled earth took the form of the multitudes who had perished there: centuries of dead entombed, from insect and fire, disease and famine, from tyrant and infidel, layer upon layer, bones thinly veiled by the grassy sod. This vastness was their monument.

“You do this to yourself,” Ilya groaned. “I thank God I lack an imagination.”

Indeed, even as Bulgakov’s moods deepened, Ilya seemed freer, more buoyant than before. As though in their travels from Moscow, an unraveling was taking place. Bulgakov felt himself coming undone, his mooring lost; whereas for Ilya, there seemed a loosening of a burden. There were times he appeared almost joyous.

Ilya was useful in his pragmatism. He insisted on routine. They ate their meals; they used the sink as a washbasin and shaved regularly. They walked up and down the aisles for their circulation then ate again. With such activity, Bulgakov’s despondency would lift for a spell.

Bulgakov spoke of his time in Smolensk. “I was prepared for nothing I saw,” he said in wonderment. “There was no one to consult, no other doctors, only the textbooks left by the last medic, and fifty or more patients each day waiting and me sprinting from the examination rooms to the books and back again.” He became quiet after a while, listening to the memories that had returned to him. Ilya seemed to detect their intrusion as well.

“This was long ago,” said Ilya. “I’m certain you were a good doctor. Come.” It was time to walk again. Afterward, he would prepare their tea.

On the whole, thought Bulgakov, it was true; he’d been a good doctor. He followed Ilya along the narrow corridors that ran between the compartments of the train’s carriages. The breadth of the older man’s back filled his vision. Yes; he’d tried hard; he’d meant well. His patients with few exceptions had been the better for his intervention. He stared at the cloth across those shoulders. An imagined bullet wound suddenly expanded in a dark and silent stain. There had been a young man brought to his hospital on a sledge; the father who drove had accidentally shot him while hunting. The young man’s clothes were heavy with blood as if they’d wicked it from him. On the examining table they peeled this away, his blood staining their hands, their clothes, the surgical linens; enough to fuel a dozen hearts, he’d thought at the time. When it was clear he would not be saved, Bulgakov instructed the feldsher to retrieve the gun in case in the shock of the news the father would turn it on himself. He appeared not to notice their intervention; once the papers had been completed he loaded his son’s remains onto the sledge. Bulgakov remembered the way he’d handled the cooling flesh, securing the ankles and wrists as if they were cut saplings that might tumble from a swaying sled. The rifle was returned to him to fend off the wolves that would take up the scent and he set out across the icy plain, presumably to his village. It was a rare winter day when the sky, though overcast, held back the snow. Between subsequent patients, Bulgakov would look and from the window or door would see the retreating figures, dark against the lighter bands of land and sky. Later, when the landscape was empty of them, he stared longer, as if he was the one who’d gone off course. He didn’t understand at the time his sense of loss. Looking at Ilya and reminded again, he wished he could speak to the father. Not about the discharge itself, but of that moment when he knew the shot had taken hold, when the body had collapsed around that button of metal, before disbelief and horror had registered. What else was in that moment? What else did he know?

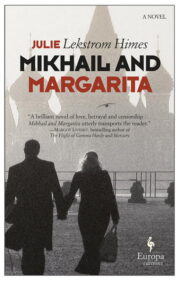

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.