Pyotrovich reached into his valise one last time and produced Bulgakov’s pocket watch. The gold shimmered white for a moment. “It can be calming to mark the passing of time while traveling across the steppe,” he advised. Bulgakov returned it to his pocket.

It seemed to fill the same space as before, as if nothing about its workings had been changed by its passage through these other hands. It still looked like a watch. It could still provide time.

CHAPTER 29

Margarita arrived at the Oserlag camp in Irkutsk Oblast, near the town of Tayshet, six weeks after leaving Moscow. No one spoke to her for the first day and a half other than to tell her to move along or that she was taking too much time in the latrine. On the third morning her clothes were stolen. She was one of the first to rise with the buzzer, still only sleeping fitfully. The back of her head ached continuously. At that hour, all within the barracks seemed grey: a fine crystalline snow had blown all night and the small, square-paned windows set high under the eaves perfused the room with a steely light. The box which had held her things at the end of her bed board was empty. She closed its lid, confused, then opened it again. Around her, others were getting up, sighing, groaning in the damp chill. She went to open the one assigned to the woman who slept below her but stopped as realization set in. Again she opened her own. She touched its bottom. There was only sawdust in its corners. The other women seemed quieter than the mornings before, as if they were watching, waiting for her response to the deed. But perhaps she imagined this. A sudden gust of wind outside lifted. Soon the second buzzer would sound, instructing them to assemble in lines to go to the dining hall. She wrapped her arms around her torso. All she had was the one thin shirt she wore. She would certainly die here. The wind rose again as if in agreement. On the other side of the barracks came a woman’s laughter. It disappeared, then more whispers. That was what they all wanted. Margarita pulled the thin blanket from her bed and wrapped it around her shoulders. A few bunks away, a woman stopped and looked at her. In the dim light she could make out only her long thin face, her dark eyes, her collected disinterest.

The woman on the bed board below groaned loudly and sat up.

“Who are you?” she asked.

Margarita touched the upper board. It seemed strange she’d gone unnoticed but in truth, Margarita had only the vaguest recollection of those preceding days.

The woman looked at the underside of the board over her head. “Well, you certainly smell better than the last one.” She stood up. She was about Margarita’s age, stocky in build, measurably shorter, with a round face and small eyes. Her skin was pale and chapped from the cold. Her light brown hair had a boyish cut. She squinted at Margarita.

“What’s wrong—goddammit, you’re crying.” She swung her arm as if she intended to hit something but it veered through the air and stopped awkwardly. Her arm was a stump, amputated below the elbow.

“I’m not crying.” Margarita stared at her arm in a way she would not have done in her other life. The woman continued to rant.

“If you cry, you might as well dig a hole and lie down in it.”

“They stole my clothes,” said Margarita.

“Who stole them?”

“I don’t know.”

The woman shook her head strangely, then turned and walked up the central aisle of the barracks. As she passed each bunk, she opened other boxes, pulling out garments and gathering them over her arms. Cries of protest followed her and women went rushing to their boxes. Halfway down, she turned around, and headed back toward Margarita. Several women tried to grab back their clothes but she pushed them off. She stood in front of Margarita again, her arms overflowing. A thin, fortyish woman appeared at her elbow. She handed Margarita’s cardigan back to her, then plucked a blouse from the amputee’s arms.

“It was ugly, anyway,” she sniffed at Margarita. A handful of other women came forward for similar exchanges. The amputee dropped the rest on the floor and others reclaimed them.

“I’m a problem-solver,” she said, grinning.

“You’re a cow,” said one of the women, shaking the dust from her slacks as she retrieved them from the floor.

The amputee’s name was Anyuta. She sat across from Margarita at the long benches of the dining hall during breakfast. Women jostled on either side of her, but she refused to budge. She talked while she ate, fixing her gaze on Margarita. It was difficult to focus on what she was saying.

“You’ve got great eyes,” said Anyuta, the way one might compliment something they’d like to borrow. Anyuta dropped her fork on her plate and covered her own eye with a fist. Her other arm moved in tandem as if wanting to mimic its mate. “I’ve got BBs for eyes,” she said. A woman passing behind Anyuta stopped and looked at Margarita.

“Anyuta has a new girlfriend,” she announced. Her tone was mocking yet there was something else about her expression. The woman raised her eyebrows, then left. Anyuta didn’t say anything but continued eating. A buzzer sounded. She reached across the table for Margarita’s plate.

“I’ll take that.” She stacked it on her own without waiting for an answer and carried both dishes away.

After their meal, the prisoners boarded a bus. The exterior of the windows had been painted in whitewash. Anyuta moved in behind Margarita in line. As they came down the aisle, she grabbed Margarita’s arm, propelled her into an empty seat, and sat down beside her. Margarita studied the window. In places, she could see the blur of dark objects. A car, the building beside them, the vague movements of people. Bubbles in the wash had flaked away leaving scattered pinholes. She leaned closer to peer through them but saw only crisp fragments. Ahead, the windows around the driver were clear. She lifted up to look but was suddenly blocked by the head of a woman who sat down in front of her.

“There’s not much to see,” said Anyuta, almost apologetically. “Just a chickenshit town.”

Were they going to the town?

Anyuta shook her head. To the factories beyond. They were building dormitories for the workers.

The bus began to move. Shadows passed across the white blur.

“What’d you do?” Anyuta’s voice was close to her ear.

At first Margarita thought she was asking of her occupation.

“My sister’s husband died,” said Margarita. “I tried to sell his clothes on the black market.” She’d made up this story before arriving at the camp. “We needed the money.”

Through the window dark shapes flickered across the paint followed by stretches of only white. Forests and fields? She began to feel queasy and closed her eyes.

“I’m sorry about your sister’s husband,” said Anyuta.

Margarita turned back to her. Anyuta had been staring at her hair; she averted her eyes. In the white light cast by the wash, she seemed more acutely weathered than before.

Margarita asked why she was there.

Anyuta made a face.

“My father was a kulak,” she said. She smiled suddenly. “Do I look like a kulak’s daughter?” She studied the window as if watching a scene unfold. The empty sleeve of Anyuta’s jacket was partially collapsed; its end was folded over and fastened with a straight pin. It rested against her trouser leg opposite its fuller mate as if unaware.

She made a sound like a small sigh.

“He’d take me fishing,” she said. “I was small and afraid of their teeth.” She shook the empty sleeve. “He’d pull the hooks from their mouths, then he’d string them on a pole and carry them to the village. He’d call on everyone to admire ‘Anyuta’s catch.’ As if he was proud.” She glanced at Margarita. “I was bothersome for my mother. I talked too much.” She smiled. “I still mind their teeth, you know.”

The bus slowed and the forms through the window took on angular shapes. Buildings. A car. This was the town. Moisture from the breath and perspiration of so many bodies had condensed on the inner surfaces and with the slowing of the bus, voices from the prisoners behind and in front of them began to lift in protest to the stifling air. On both sides, arms went up and windowpanes were dropped down. Crisp snowy images of brick and planking and glass darted past. A brief chorus of gladness rose up as the cold whiffled through the bus. The guard who sat next to the driver came down the aisle waving a baton from side to side and ordered the windows shut.

“No one’s supposed to see us,” said Anyuta.

In his wake, from the front to the back, the windows rose up again. Margarita half-stood and watched as the world slid away. Once they were closed, she sat down. Rivulets of water now streaked across the glass. The air was cold and damp.

She’d heard of prisoner jobs in the towns, outside the camps and the typical work sites. Jobs with less supervision. She would have to get one. She would have to be seen as trust-worthy. She studied the empty sleeve beside her. Perhaps Anyuta could help her. Anyuta the problem-solver.

“Is it hard to get a job in the town?” she wondered aloud.

There were always such jobs, Anyuta told her. The people who took them would try to escape and get caught. She held up her hands as if firing a machine gun. “Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch,” she said, sweeping it at the seat in front of them.

The woman across the aisle looked at Anyuta then away as quickly.

“They always get caught,” Anyuta repeated. She touched Margarita’s sleeve. “Don’t get caught,” her BB eyes pinned her back. “Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch,” she warned.

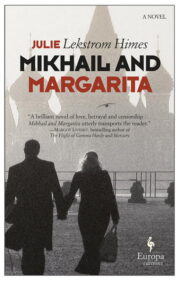

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.