She suddenly seemed tired, as if all of this speculation was too much. She leaned against the cushion and went back to frowning at her nails. Supper with him had been forgotten. “It makes no difference to me,” she said to herself.

“I don’t know any of that,” he said softly, glancing at the shared wall between them. He knew so little as to fill the head of a pin.

“Now it’s you who’s seen a ghost,” she said, musing. She appeared to make little else of his surprise. The light in the room seemed to have grown in intensity and in it she looked even younger than before. A child’s face could be seen through the wash of day-old makeup. She looked desperately hopeful for so many things.

“Tell him I’m expecting my fruit,” she said. She seemed to be trying once again to sound casual and upbeat. “He promised.”

He told her he’d tell him.

“If she doesn’t come back—your fiancée—I can be your friend,” she said. Her offer seemed a vague thing—after all, he couldn’t be expected to produce fans or teeth. Still, one could keep an open mind.

He didn’t know what else to do but to thank her.

He entered Ilya’s apartment without knocking. Ilya appeared to be neither surprised nor bothered by this. A suitcase was spread wide on a low table. Beside him on the sofa was a pile of clothes. On the chair were travel documents. Bulgakov moved the papers and sat down.

“Annuschka said you are taking a trip,” said Bulgakov.

“Don’t worry about Nushka.” His voice was gentler than Bulgakov would have expected. “She has a gift for finding someone to take care of her.”

Ilya turned the case sideways; then, as if this was a most natural thing, he lifted the lining from the lid’s interior and released a panel that hid an upper compartment. He went to the bureau and returned with a second pile; this was of women’s clothing. He began again, only this time, there seemed to be a kind of reverence to his motions. He smoothed a blouse of filmy cloth then laid it in the curve of the case. The loose threads caught on his coarse skin and the fabric lifted as if it was unwilling to let him go. He as well seemed reluctant to retreat; his hands hovered as if to coax it to stay.

“There’s a strange parcel,” said Bulgakov. He felt helpless and angry for it.

Ilya picked up a grey skirt and folded it lengthwise. He placed it in the suitcase, but its hem and waistband seemed uncooperative and hung over the lid. He pushed down its edges, then, unsatisfied, lifted it out again; this piece would require another strategy. His concern seemed excessive, as if it was more than a skirt.

“This is unlike you,” said Bulgakov; he wanted to sound skeptical.

Ilya continued to work. Writ on his face was an unexpected vulnerability; a combination of hope and nervousness and measured anticipation. By it he seemed a much younger man, as though he’d been freed of the burdens of wisdom and experience. He could believe in something that was close to impossible. He would give himself the luxury of that faith.

“When are you leaving?” asked Bulgakov. The question itself depressed him further.

“At the end of the week. Though I’ve been delayed once already.”

A small pile remained beside him. A cluster of women’s undergarments, and he hesitated above their silken glory, his hands paused in a kind of nervous devotion.

“What are you planning?” said Bulgakov.

“I don’t know.” Ilya seemed to answer to their daintiness, as though made helpless by it. Finally he took them, en masse, and pressed them into a corner of the case. They would have to suffer a certain amount of boorishness. They would have to forgive him this.

“Then—after—where will you go?” This was the dangerous question. If Ilya was successful he would be with Margarita.

“It’s a big country,” said Ilya. He was willing to point out the obvious.

Bulgakov would never see her again.

Ilya closed the lid. He set it on the floor then went to pour himself a drink. He worked over a small sink that hung from the wall, similar to that in Bulgakov’s apartment.

Perhaps he’d asked Ilya for one—he couldn’t remember, yet Ilya handed him a drink. The glass was crystal though badly chipped; some remnant of old, discarded wealth. Bulgakov held it in his fist. Its wounded surface bit into his skin.

Ilya stood near the sink, empty-handed, studying him. “I can take care of her,” he said.

He was neither apologetic nor boastful. He’d perused maps and collected false papers. He’d made provision for travel. He could appear at the camp under the guise of authority and communicate some plan to her. She could act on that plan. He was her best chance.

“I can make her happy,” said Ilya.

“No.”

Ilya didn’t argue with him. Perhaps he questioned himself. “I can take care of her,” he repeated.

Bulgakov gripped the glass. “Were you at least going to tell me?” he asked.

Ilya’s expression was surprising. He seemed of all things embarrassed.

Did he think he would follow him to Siberia? He could imagine only the emptiness of that space. Its tundra a frozen ocean. A quiet so profound one’s ears rang from it.

Did he think he would stop him? Report him to the authorities? Relegate her to years in prison, perhaps worse, just to keep him from her?

Or would he stay and get on with his life? Enjoy his literary fame. This was his moment. There would be parties, glittering honors. Lesser writers would vie for his attention; great ones would usher him into their midst. There would be people to fill rooms. Rooms upon rooms. He would not be alone.

There would be Annuschkas aplenty.

Bulgakov downed his drink and set the glass aside. His hand was bleeding from scores of tiny cuts. Blooms of red appeared in a fresh and unexpected crop.

He wondered, momentarily, if she would have been surprised by his decision.

CHAPTER 28

Bulgakov obtained travel papers from a man whose name Stanislawski provided. For as illegal as the transaction was, it seemed oddly cordial. They met at the man’s apartment in the middle of the afternoon; the man had been late arriving and apologized as he opened the door. He offered tea and seemed genuinely disappointed when Bulgakov declined. He drew some official-appearing pages from a desk, then asked about his destination. He scratched in the name of the town with a quill pen. He appeared to add other particulars of his own invention; Bulgakov tried to decipher the movements of the pen. When he was finished, the man took what appeared to be a block of wood from the lowest drawer. The block separated into two halves and he placed the paper between them. Here, he got up from his chair to leverage his weight and with both hands pressed down on the seal. He stared at Bulgakov as he did this. His gaze seemed vaguely inquisitive. Then suddenly he smiled. “This is it, isn’t it?” he said. It was this for which he’d paid his money. He separated the blocks and handed him the page. The seal was crude, blurred, it seemed clearly fraudulent. “They don’t look very carefully,” he said, as if anticipating the complaint, and took the page back and folded it. “Most of them can’t read.” He found an envelope. He seemed to interpret Bulgakov’s hesitation as disappointment. “It’ll do the trick,” he said. “Haven’t lost one yet.”

Lost—to where? Prison?

Bulgakov then asked about acquiring a gun. He felt sheepish, as though the asking made him already guilty of some crime. The man pulled a large metal box from under his bed. A variety of firearms were within. He squatted, his fingers on his lips; he glanced once at Bulgakov then back at the box, as if he was fitting a suit to a man. Finally he selected one. He sat on the bed as he explained its parts, then passed it to Bulgakov.

The piece was heavier than he’d expected.

“It’s a Nagant,” said the man.

Bulgakov didn’t know what that meant. “I see,” he said.

“It was standard issue before the TT became popular.”

He wondered if he shouldn’t ask for the TT instead.

“It’ll do the trick,” said the man.

“I hear it can be a wild place,” said Bulgakov.

The man gave no reaction. He’d participated in scores of illicit transactions; he was beyond any need for understanding the particulars of these things.

Bulgakov offered it back. “I’ll think about it.”

The man didn’t move to take it. “Best to think before you need it,” he said. “It won’t take down the People’s army but it might slow down a wolf.”

Bulgakov hadn’t thought of wolves. What other dangers had he not considered? He tried to accustom himself to the weight.

The man sold him a partially filled box of ammunition and showed him how to load it. Finally he found a paper bag from a closet, so Bulgakov might carry it discreetly.

Bulgakov went to the station in central Moscow. Timetables were not to be trusted and despite the hour the platform trembled with the crowd of huddled bodies. In their midst a locomotive towered. The air was dry and bitterly cold. Half a dozen darkly rusted metal casks were scattered throughout the crowds; therein small fires provided some warmth to those waiting. Working men called to one another and cursed. Trestles groaned, pallets of goods were loaded and unloaded. Whistles and horns floated in from the street. A garbled, indecipherable announcement came from a loudspeaker. All of this made for the moment of departure: when the familiar lost its claim on one. With this the blood moved faster, looser, limbs warmed. Even the discomfort and inconvenience of travel could not dissuade. Bulgakov needed to find one who would be willing to give this up. He was willing to pay.

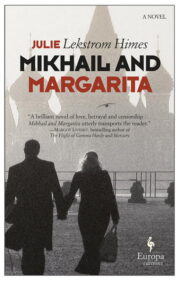

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.