“You may leave now,” he told the guard. If the guard felt this was irregular, he gave no indication. He departed and the door closed. Ilya pretended to focus on the reports. He heard the other chair shift as she took her seat.

He turned the pages one by one as if they required some careful inspection. The text rippled across the page; he read none of it. She was silent; not even the wisp of her breath could be heard. There was only the sound of moving paper. He sniffed, then rubbed his brow as though something he read had pained him. He cleared his throat but still said nothing. All seemed staged, only he’d been given no dialogue. He was at a loss as to how to begin. The reports offered nothing. He reached the end and started to page through them again.

Her hand rested on the table. Her skin seemed translucent.

A phrase on the page caught him: The prisoner smells of lavender today, the source of which is inexplicable.

He knew then. She’d not survive that first year in prison. As though she already carried her contagion dormant in her chest, biding its time. Across the steppe, then into the Urals, as roads became trails, then paths, it would awaken. As food and supplies dwindled, as the cold took its turn, the entity would grow. It would break down her tissues and rebuild them to its own specifications. After a time, after much suffering, whatever remained would stiffen in an unmarked grave.

Even in the stale, overwarmed air of his office, this future was as real as if it’d already occurred. Behind her shining eyes, he saw dead ones staring back at him. As if there were two of her, the second in the background, waiting, certainty giving it patience; its turn would come. The hopelessness of the moment rose in him.

“You’re to be sentenced tomorrow,” he said quickly, his voice deepened. “It’s more of a formality, in truth. The decision’s been made.” He pushed the disposition letter forward. He watched her read it. Her expression didn’t change from the start of it to the finish, as if she’d expected it.

She placed her hands in her lap. He had the sense she’d withdrawn not in anger or regret, but rather so as not to taint him. He could not see what she was doing below the tabletop; if she was praying, or wringing her hands in despair. He wanted to take one hand back in his, he wanted to separate it from the other as if apart they’d be easier to persuade.

“How long?” she said. It was the only sound in the room, yet it seemed he strained to hear her.

“Eight years.”

She lifted her hands to the tabletop as the drowning might, as if to steady herself on a piece of flotsam.

He weighed the expanse of this for her. His words were soft.

“This is exile.”

All things she knew and loved, all freedoms both cursed and enjoyed, would disappear. The tips of her fingers whitened where they pressed down.

Those hands would look different after a few months.

“Why wasn’t he arrested?” She asked this without rancor. It was the most natural question.

How could he answer? His frustration with her dissipated a little into a more general disquiet with the rest of the world. Her arrest made his unnecessary.

He tapped the paper. “This doesn’t have to happen. If you give them something, something to indicate you’re willing to work with them, they will make an arrangement instead.”

“An arrangement?”

“Something that happens here every day. Many times a day. For many, such as yourself.” He was given to a vision of Muscovites, thousands of them, walking the streets, looking over their fellow citizens in the stores, in the parks, on streetcars, evaluating their deeds, their words, their hearts. Listening. Always listening. Knowing better than to speak themselves.

“I’d make a terrible informant,” she told him.

It seemed like a small thing, in exchange for her life. “Do you think that you are protecting him?” he said.

Her face held not an answer to this, but a different question. If she took this offering, how was she to return to Bulgakov? Now with the ability to destroy him? With the expectation to do so? Perhaps she’d already envisioned this darker future. Perhaps she thought she was saving herself.

He wanted to tell her that no one escapes these kinds of choices.

She took the disposition letter and reread it. “You can sign this,” she said, as though it was her permission to give.

He didn’t want her permission. He certainly didn’t need it.

“I don’t want to sign it, but I will,” he said. “When you leave this room, when this meeting has ended, I promise you.” His words had become threatening; he wanted her to feel threatened. He got up and paced. Behind her chair, then back again. “This is real,” he went on. He couldn’t see her expression. It was easier this way. “They will load you on a train like livestock. Worse than livestock. Livestock they care about, you they won’t.” There would be typhus. Disease. He would never see her. Did she care about such things? “I won’t be able to help you. Do you understand?” He picked up the pen and threw it across the room. It hit the wall and scuttled to the floor leaving a mark.

“Don’t do this to me,” he said.

He thought he was prepared for this outcome.

Something he’d said had set her in motion. She seemed at a loss over what to do with her hands. She slid them high under her arms, trapping them; her arms pressed tight into her sides. As if she was trying to hold herself together.

“I’d like to go now,” she said. She glanced around the room as if to escape.

“Give me something. Any bit of information. You don’t know what will happen to you.” He stopped there. It was difficult to continue.

Her shoulders were square; her hair hung past her shoulders, no different than before. Not a strand moved. She would not be moved. It was no use.

“I’m so very angry with you,” he said quietly.

He picked up the pen and signed the letter. He dropped it against the table as if it’d done this thing on its own. He pushed the page away.

“Goddamn you,” he said.

He suddenly felt old and filled with regret for impossible things. Their impossible situation. Was he flattering himself to even call it a situation? He would never see her again. He combed his fingers through his hair. “I’m old enough to be your father,” he said. Where had those words come from? Those were the last he’d intended. How did she cause him to reveal himself? Did she think of him in that way? What could those unfathomable eyes see? In truth he was afraid of them. He was afraid he’d see only a tepid sympathy for an old man’s unrequited affection. He was afraid he’d see nothing.

From behind, her head seemed immutable. Perhaps she had no feelings for him. Perhaps all had been imagined.

He sat down, weary. His hands rested loosely on the table near hers. They were so unlike his own.

She touched a finger to his. Then drew it lightly over his skin. He sensed her gaze. Was this only sad kindness? He looked up from her hand.

She’d heard his confession for what it was. He saw her understanding, perhaps even her reluctant acceptance of it. It seemed on her to be a kind of miracle.

Love was a wholly selfish thing. He would not give this up.

He turned over the ashtray onto the table and spread out the ash. A thin mist of grey hovered above. He traced words as he spoke.

“Your sentencing is scheduled for tomorrow. It would have been easier for you, Comrade, had you chosen to help us root out these enemies.” He paused, intent on his writing. “But you did not.”

In the ash, he’d traced They are listening.

Her head tilted as she read it. He wiped the ash back through the words and continued.

“Our actions may seem capricious to you, but I assure you, they are not. There are those who would thwart our efforts to build a sound and worthy nation. They are cowards: selfish and lazy and morally destitute.” His last word was drawn out, as he scrawled through the ash again. There was an awkward pause for any listener beyond their room. When he was finished he drew his finger across the table under his words.

She read his words and nodded. He passed his hand over them and began to write again.

“I am no different than you,” she said. She watched his finger work across the table. “I want a healthy and productive country, like all good citizens. I love my country. Of those few you mention, if I knew any, I would certainly hand them over to you.”

He smiled at her words. They sounded like a terribly written radio play. She leaned her head toward him and tried to read as he wrote.

“Then it is a shame you were less than convincing for your interrogators.” He moved his hand away so she could read. His fingers were thick with the dust. “You will be an example to others. May you spend your years in Siberia hoping that other citizens will learn from your error.”

He saw in her face a fresh despair. He went to wipe the words away as if they were the cause, but she held his hand back. He felt immobilized.

I will find you

Hold this close

Then, at the bottom, in the faintest layer of ash, he’d added:

Believe in me

Her fingers tightened around his hand.

PART IV

MIRACLE, MYSTERY, AND AUTHORITY

CHAPTER 27

Ticket sales for Molière had tapered off. Bulgakov attended one night; he guessed that a third of the seats were empty. Those who were there, however, appeared engaged, and their applause was sincere. He said this to Stanislawski backstage after the performance. The director looked grim. Bulgakov gave an interview for Crocodile and sales showed a nice bump. Stanislawski hosted a lavish after-party at the Writers’ Union. Several committee members attended. Rumors were started, no doubt by Stanislawski, that the lead actor and his co-star were having an affair. The following week, Pravda ran an article, and afterward reservations could only be made months in advance.

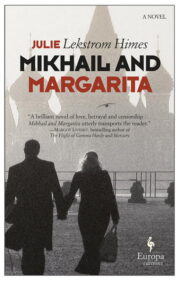

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.