She stood over the worm. Even the whitest soul could not stay forever unsullied. He could imagine she was not so white. From beyond the wall came the muted and intermittent blare of a car horn.

She turned to him. “I’d forgotten,” she said. The horn sounded again. Her expression changed. Even a world of car horns was something to long for.

Her ease with him unnerved him. As if something was missing from his uniform or his demeanor, and he was less recognizable as a guard. He pushed the remainder of his cigarette into the wall.

Or worse, she had read a different politic on his face.

The door opened. Another guard with a prisoner appeared. He said he’d thought the enclosure was empty. He looked carefully at Margarita. “That one doesn’t get a breather, mate,” he said. “People’s Enemy. They should have told you.” He left with his prisoner to find another enclosure.

They were watching. They were wondering if he still recognized himself.

“Let’s go,” he said.

He saw her disappointment and he looked away; she passed before him through the door.

She reminded him of his sister. His mood sank further when he realized this. She would have been similarly transformed. The same stooped walk. The same held face. She’d have saved the fragile worm without envy of its salvation. He imagined her expression, the gentle smudge of her quizzical forehead, should he have suggested otherwise. He thought of her skirt, fiercely embroidered, weighted along its hem like a fisherman’s line.

At D-block he was told her cell had been repaired and he should escort her back. Someone offered to take her if he wanted a break—he said no, of course. A break wouldn’t make sense; he’d only just started his shift.

As they ascended the stairs they passed one of the interrogators coming down. His reputation was well known. The guard took her arm and maneuvered her along, placing himself between them. The interrogator stopped just as they passed, on the same step.

“We missed you today, whore.” He grinned at her and wagged his head in mock concern. “I guess we can’t let a prisoner’s feet get soggy. We’ll have to double our time tomorrow.”

She swayed slightly. He wondered if she might faint.

“Excuse me, friend,” said the guard. “I must get her back to her cell.”

The interrogator ignored him. “Perhaps I’ll request an extra session today,” he said to her.

Whatever he saw in her expression caused him to laugh.

“I’d be forced to work late, you know, but if you beg me, I will.”

The guard placed his foot on the next step. The interrogator didn’t move.

“Beg me,” he ordered her.

“Comrade Interrogator,” the guard began.

“Shut up,” said the interrogator. “Beg me, whore.”

“They are expecting her back,” said the guard.

“What’s your name?”

He told him.

“Well, Miklosh,” the interrogator immediately applied the diminutive form. “You should make it your job to care about what I care about and not worry about other wormlike guards like yourself.”

“I beg you,” she said.

They both looked at her.

“What’s that, whore?”

“You heard me.”

“I want to hear it again.”

“You’ll have to tie me up first,” she said. Her words were matter-of-fact, as if she was reminding him of a familiar practice; one they’d agreed upon long ago.

The interrogator laughed and set off down the stairs. “And I will,” he said. His words rang from the cement walls. They heard him then shout to someone below and hurry his descent. A lower door opened then shut.

She leaned against the wall. He urged her forward. “Come along. We’re almost there,” he said. Words that might be a comfort under other circumstances clearly were not here. He thought to give some apology for this blunder.

“Listen,” he said. His grip on her arm tightened to the point he thought might be painful; he needed to wake her up. “The writer wants to know of you.”

She was silent at first, as if she couldn’t make sense of his words. “You’ve talked to him? Where is he? Is he here?”

“No—he’s outside. Don’t say anything more.”

She obeyed him. He was surprised by this and almost regretted the command. At her cell block he turned her over to the guards. He could see she was careful not to look at him.

On his way back to D-block, he stepped into the alcove they’d occupied earlier and lit another cigarette. The mist overhead had lifted revealing an empty sky. His hands shook for a few moments, then calmed. A car horn sounded. This calmed him further.

He went to the place where she’d released the earthworm and squatted. He stroked the dirt. It was nowhere to be seen. He heard wings and a blackbird landed on the top of the wall. It eyed him, then toggled its head back and forth.

He removed his hand and stood back from the spot.

The guard learned in subsequent days that she’d been put on the list for deportation to a Siberian camp. Again, his gain of such knowledge appeared serendipitous: a glance at some documents he’d been asked to deliver to another unit. He wouldn’t tell Bulgakov this news. That would’ve been an additional hundred rubles, he reasoned. Besides, what difference would it have made? He’d do better to keep his money.

Bulgakov returned with the beer.

The guard was gone and Ilya sat in his place. Ilya took one of the bottles.

Bulgakov sat down. He wondered what—if anything—had transpired between the two. Or if perhaps the guard had transmogrified in some way. The evening light seemed tricky.

“It’s not that warm,” observed Ilya. It wasn’t clear if he was referring to the drink, or the weather; a reference to the waning year. He tipped his head back and drank. The bottle was half empty when he lowered it again. He delivered his news without preamble.

“She’s been sentenced to eight years. The penal camp of Oserlag. The best I can do is have her processed as a common criminal.”

The bell of a distant streetcar announced its approach.

“That information,” said Ilya, with a touch of sarcasm. “Cost you little to procure.” He indicated the beer.

Ilya got up, leaving the bottle on the bench between them, and took the path toward Bronnaya Street. He crossed; the streetcar passed between them.

Along the street, one after another, the gas lamps were being ignited. Restaurants were opening; people still wandered there. The kiosk which had sold him the beer was closed and dark. The park was empty except for him. It was beyond twilight; darkness filled the spaces between the benches, along the paths, as easily as did the light during daylight hours, yet there was the sense it harbored other things. Those who required their eyes to navigate the world had no business there.

CHAPTER 26

Ilya wanted to tell her himself.

He stood in his office and stared at the photograph of Stalin on the wall. His was different than Pyotr’s: the Great Man’s gaze was slightly lower. One could imagine his domain was more personal; perhaps one’s own particular cares figured there. Ilya looked at his watch. Momentarily they would arrive, the prisoner and her guard, and through the wall he would hear the movement of chairs, muffled words, some fidgeting, then silence. They were always silent while they waited for him. He hadn’t seen her since the day of her arrest and he realized he was anxious. Anxious of her changed appearance. Anxious she would blame him. Did Comrade Stalin have insight to share? Could Father Chairman provide counsel? How did one woo a woman whose sentence one had enacted? Ilya stamped his cigarette into the ashtray.

The reports of her interrogations had been transcribed on papers as thin as onionskin. They lay on his desk in a dainty stack. Young Fedir was fastidious, his language nearly clinical in its descriptions. In the typing, his machine had dropped every “r” to the level of subscript, and it was easy to become distracted from the prose by the undulating waves of print. But then a phrase would find him—the prisoner seemed frailer than usual today; will consult with the infirmary regarding iron supplements. He reread those lines. Did he, he wondered? Had the medics acted on this concern? There was no further mention in subsequent reports. Was there a usual level of frailty that required no action? A subtle shift in the hanging of her dress? Bluish shadows under her eyes that told of malnutrition and sleeplessness? The young interrogator had come to know such specifics and Ilya disliked him for this.

Overlaying the reports was a single page with the recommended disposition. It was the standard text. The prisoner was an excellent candidate for rehabilitation, so it read. She would derive great benefit from Siberia’s robust frontier and the opportunity to make a dedicated contribution toward the strengthening of the Soviet infrastructure. She would learn firsthand of the joy in communal living and the satisfaction of working with others toward the larger purpose.

Ilya traced his fingers downward. Below Pyotr’s signature was a place for his.

He signed such documents every day.

The outer door in the adjacent room opened. Two people entered but there was only the voice of the guard. He’d typically wait as long as a quarter hour, but he could not help but think: She is here. He opened the door. They had just settled into their chairs and immediately they rose.

She was thinner than before. She appeared surprised to see him and this unsettled him. He looked away, not wanting to know more until they could be alone. He’d carried the stack of reports with him. He grumbled of being too harried and pressed for time. He put them on the table; the pen beside them, and took a seat.

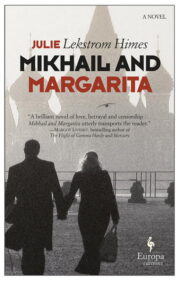

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.