The details of his arrangement with the guard from Lubyanka seemed laughably transparent. Bulgakov knew it could be anyone who might act as an informer. It was the girl server whose gaze now followed him from the tearoom’s window, down and across Teatralny toward Tverskaya Street. Who glanced then at the man at the counter then back to the glass and suddenly understood that she would never see her customer again. It was the man’s co-worker, a fellow guard in the D-block of Lubyanka, who observed aloud that for the second day in a row the man had been late for his afternoon cigarette break. Who noticed that his words were ignored, that the other simply lit his cigarette then spoke as if something entirely different had been said. It was the man at Patriarch’s Ponds who would sell them two bottles of ginger beer and pocket the extra change he’d held back from the one who seemed nervous. It was the housing commissioner of the guard’s apartment building who’d been annoyed by the late hours he kept and simply wanted his room in order to house her recently divorced sister and her sister’s children.

With the rain, Patriarch’s Ponds had been abandoned and the kiosk shutters closed and Bulgakov sat alone on an empty bench under a linden tree. To the west, the sky was clearing and the light swelled even in the declining hour as if someone had peeled back a corner of its stormy roof. The rain had stopped.

A screech of steel against steel sounded and the kiosk window rolled open. The guard from Lubyanka sat down on the other end of Bulgakov’s bench. The kiosk seller poked his face through the opening and looked at them. His head disappeared.

The guard opened the bag of teacakes and offered it to Bulgakov. Bulgakov shook his head. The guard removed a cake and inspected it briefly. He confessed that he ate constantly and he took a bite. He always had and yet he looked like this. He gestured to himself. He said the cakes weren’t half bad. Perhaps a little stale.

Bulgakov asked about Margarita. The guard finished chewing, then looked away, down the sidewalk that ran in front of them toward the distant street.

“I brought payment,” said Bulgakov.

The guard told him she was being interrogated.

Bulgakov paused before his next question. What did that mean exactly?

The puddles in the walk caught the light of the sky. The air smelled wet and moldy.

The guard had heard of her interrogators. Their reputations. She could have done worse. He took another bite of the teacake.

Had she been tortured?

Not that he could see.

“It took me a bit to find her,” he said. He removed another teacake from the bag.

Bulgakov took a roll of bills from his pocket and placed them on the bench between them.

“Were you able to give her my message?” asked Bulgakov.

“Do you suppose they sell anything worth drinking?” said the guard. He covered the bills with his fingers, then slid them into his trouser pocket.

The price was just over a hundred rubles.

Bulgakov went to see.

It’d been about the money. The guard was certain that the man would pay whatever was asked. The man had worn a suit when they’d first met, old but not frayed; the chain of a watch fob was visible though he never saw the watch. He’d become good at sizing people up and gave the price. The man had hesitated, but when he made to leave, he quickly assented. He was good at sizing up. It came from observing a multitude of prisoners, the rich and the formerly rich and the poor and the penniless, flowing past him every day. People were base creatures. They only valued that which was painful to acquire. Once the price was set, the man was quiet. A hundred rubles was steep for information. The guard added then that simply finding one prisoner among the thousands held there would be no small trick. The man nodded. Perhaps that had made him feel better.

Finding her was not simple. He asked questions he’d not normally ask; took interest in conversations he’d typically ignore. He knew his change in habit was noticed and he ignored this as well. He saw her only twice. The first time no words were exchanged. She had no idea she’d been the subject of such scrutiny. He suspected she was being held for interrogation. He listened in on the conversations of guards assigned to those wings. After several false leads, he fabricated an errand to one of the midlevel blocks. He saw her as she was being escorted back to her cell. It was simply a moment; for some reason she turned as she passed through the riveted door, for some reason her gaze rested not upon those who’d brought her back but rather on the corridor beyond, on the one unfamiliar face. She did not look away from him, even as the door between them closed. She was the kind of woman who was accustomed to the stares of others, both men and women, he knew. But she’d know in this exchange that his chance appearance was not chance. He was certain of this even before their second meeting. She would be waiting for him.

He had only a sister who worked on the sly as a seamstress, sliding the extra kopeks gleaned from her guilty customers into little pockets she had fashioned in the hem of her skirt to hide them from the Kolkhoz inspectors. Their mother had left them in 1905 and she had raised him even though she was barely older and certainly no bigger. He’d only seen her once since coming to Moscow. She sent frequent letters. He had the sense that she wrote them thinking she was writing to the world. That they would be opened and read and collected and filed was not her concern. She complained that he rarely wrote and when he did, he said nothing. She gave no warning of her visit. The evening he’d found her waiting in his apartment was one of record snowfall in the city. She was sitting in his armchair with her bare feet propped up on the seat of another. The snow that had dusted his shoulders began to melt and he felt the cool dampness sink through the wool. She said she’d brought the storm with her. Her small frame was enveloped by the chair. He took off his overcoat. She refused to be extricated from his life. He kissed her on the forehead. She waved her hand about his apartment. What was it about the two of them, she said, that they should both live their lives as a solitary endeavor. He told her he preferred it that way.

He saw the prisoner for the last time several weeks after the first.

It was a chance meeting and he was ill-prepared for it. She’d been moved to his cell block in order to repair a broken pipe that was flooding her cell. He’d not given a thought to what he might say to her. Despite the arrangement and the agreed-upon sum, he never really thought the opportunity would arise.

When he arrived for his shift that morning he was told to escort the prisoner in D-242A for her quarter-hour breather. There was a light rain and his clothes were still damp from it, yet it was a better alternative than making the rounds and collecting food tins. D-block guards unbolted the stenciled door. He joked with one of them, some reference to a woman he’d seen him with at a bar the night before. A woman well above his pay-grade, he suggested. The door swung open and he saw her. He saw her and saw his own surprise and uncertainty reflected in her face and could think only of the implausibility of their meeting being random. They—the unknowable, unnamable they—knew and had decided to allow for this happenstance. They would be watching. He didn’t hear the other guard’s response. Someone else nearby laughed at something that had been said.

He directed her along the corridors with single-word commands until they reached a series of doors. He unlocked one with a key on his belt and revealed a small outdoor alcove. Its grey light glowed in contrast to the dark inside. The outdoor space was boxlike; three meters square with two-meter-high concrete walls. The ground was dirt. The earlier rain had changed to a low mist. She entered and turned around in it. Her posture was slightly stooped.

“How much time do I have?” she said. She seemed both in awe of this freedom and reluctant of it.

He told her a quarter hour. He realized then that she’d not been let out before; typical prisoners were given time for exercise each week. This made it likely she was a political and at once she became a much greater danger to him. The likelihood of their situation being chance was even more remote. He lit a cigarette and leaned against the wall. They could watch all they liked, he decided. They could listen to silence fill their ears. He had no intention of talking to her.

“It’s funny; you look like someone I know,” she said.

He looked at her hard, and, he hoped, discouragingly, and continued smoking. Did she have any idea of how stupid she was being?

“Like the younger brother of someone I know.”

“I don’t look like anyone,” he said. That’s how they pick us, he wanted to add. We are the ones with forgettable faces.

“Well, he is a nice man and you look like him.” She spoke as if she’d held her words for so long that now she’d begun, they were beyond her control.

“We can make this a three-minute breather instead of fifteen.” He wasn’t willing to take these risks.

She pressed her lips into a thin line.

Small puddles had collected on the uneven ground near one of the enclosure’s corners. From one she rescued a drowning earthworm. She showed it to him before depositing it on moist soil. It arched up from her palm then fell back against it, its mass in the air too much to support. She placed it on higher ground then stood and rubbed her hands together. As if she could find more things to save. He thought—here she stands, for the moment vast and almighty; the low and mindless at her feet. Did she not feel some urge to squash it into the dirt? To stand square with those who still moved freely in the world? To wield the same power as those who would crush her? Did her toe not turn, its compulsion growing, held back only by her initial horror of the imagined act?

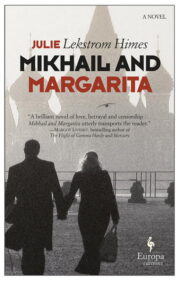

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.