“I’ll bet you can do lots of things,” he said. “I thought we’d start slowly, being your first time.” He pushed the tip of the baton between her knees. “You were Mandelstam’s whore. Tell me about him.”

She couldn’t speak or think, only wisps of air came from her. He pushed the baton upward a little.

“We don’t have to start slowly, whore.”

“I—I don’t know—I mean, what do you want to know?”

He removed the baton and sat back.

“What was it like—your first time with him?”

She struggled to find words. He looked bored, then he wagged the baton in her face.

“I think you can do better.”

She started again; her vocabulary became more eloquent as she went on. He brightened at first, then seemed to grow agitated as he listened. She stopped, uncertain that she might be upsetting him. He growled at her to go on.

“Tell me what it felt like the first time you put that bastard’s cock in your mouth.”

Her voice seemed to come from a hole behind her head. She went on, feeding him words, words she never used, and his breathing deepened and he started to grimace. He stopped her again and had her repeat herself. Finally, he sprung from the stool and struck her with the bat across her cheek. The walls flickered with pinpoints of light. She had satisfied him.

Each day he questioned her then beat her; afterwards he’d sit awhile until the red of his cheeks faded, until his breathing steadied, until the trembling of his hands subsided. Then Mark would have his turn. Mark was interested in other things.

It was Mark she could imagine as her lover. Shorter and more compact than the sprawling and emotional Matthew, he maintained a stillness in his features during their exchanges. It was only when he would step away, remove his wire-framed glasses, and wipe them carefully with his handkerchief that the silent and muscular John would step forward with a short leather-sheathed bat. Then she knew she’d touched him in some way. She heard her voice exclaim in short beats as John laid into her; each slap against her thighs and buttocks followed by a bright burst in her brain. Eventually he would tire and the cadence would slow and her exclamations would crescendo into round moans. When the beating was finished Mark would fold and return the white cloth to his pocket, slip the glasses back behind his ears, and raise his eyes to her again. He was patient with her; he forgave her these interruptions. She imagined him dressing in the morning, thinking of her as he took each button through its hole, as he looked in his mirror.

Most of the accusations were fabricated. Associations with people she’d never known, conversations that had never taken place, meetings impossible for her to attend as she’d lived somewhere else at the time. She commented to Mark once that his fiction was compelling.

She was told her attitude did not help her. When she returned to her cell, a metal shutter had been screwed over the window. Where the clock had hung there were only wires.

When alone she tried to imagine all they could do to her, the worst they could invent. And when they did something new, she’d return and examine her limbs, press on the bruises, and recall the memory of their specific tools. In the places she couldn’t see, she’d trace the swellings with her fingers.

At night the guards woke the prisoners repeatedly. It was difficult to estimate the passage of time. One morning Mark happened to mention she’d been there for twenty-one days. She’d counted over twice more and with this she cried. For one strange moment he looked apologetic. Puzzled and pained and perhaps in some way embarrassed. As if he had inflicted a wound he’d not intended. The room was silent. Tears took random paths down her cheeks and lips.

Later, after her escorts had returned her to her cell, she imagined the other interrogators ridiculing him for ending the session early that day. She knew the same as he knew: he’d given up a temporary advantage for reasons he didn’t understand. She imagined he’d complain of a headache then retreat to the infirmary for an aspirin.

Usually they talked about Mandelstam. One day, he wanted to talk about Bulgakov. He suggested the topic as if he were suggesting an outing on a fine day. Matthew was home with a mild fever and they’d not yet tied her up. Mark offered her the extra chair. She sat down. Its padding was thin and the underlying curve of its metal support pressed into her tailbone that’d been bruised during their last session. She shifted. She rested her arm on the table. He sat facing her, his arm resting like hers in a mirror image. John stood near the door. She allowed her feet to lie flat on the floor.

Since her arrest, she had wondered if Bulgakov had been taken the same night. She feared for him, that she might implicate him in some way. Sometimes she envisioned him in a nearby cell, staring at the same colored walls, eating the same watery soups and old bread. At night lying on her bedboard she imagined them reunited in sleep, his arm around her waist. Other times, but not at all times, she grieved for his lost work. It was easiest first thing in the morning, after she was awakened. Later, when her interrogators were finished, she cared less for his words. They flitted about her like moths, thoughtless of the difficulties they had caused her. By the next morning though, she felt guilty for this betrayal. As if in the night they had fought their way to the light and by morning their carcasses were scattered on the cell floor, upturned and motionless. She was regretful for such an end to their short lives.

—Let’s talk about Bulgakov

—I’ve heard of him.

—You were found in his apartment.

—I’ve been found in many people’s apartments.

—Do you like his work?

—I’ve never seen it.

She wondered why she aligned herself with writers. Surely men such as her interrogator had come through the doors of the stores where she shopped, the cafes she frequented. She could have smiled at their attempts to tease her name from her; she could have let them take her to the movie theater and buy her flavored drinks. In the flickering darkness she could have let their fingers wander over the seam at her shoulder, move to the curve of her neck. Afterwards, they’d have talked about the movie, the news in the papers, the latest feats of their local Stakhovite. Later they’d have gossiped about their neighbors and friends. The shape of their lives together would form about such things. If she picked up a book to read, she’d give no thought to the writer who’d penned it for her. It might be nice to think nothing of him.

Mark drummed his fingers lightly against the table. During their time together, he seemed always to have formed an opinion as to whether, with any particular exchange, she was lying. For the first time, he seemed uncertain. He motioned to John and when he came over, he spoke in his ear. She stiffened; she dreaded being beaten again. She didn’t think she could take it; not after sitting in a real chair for so long.

John left the room. Mark went on. His fingers quieted.

“I saw the play, The Day of the Turbins.”

“I wouldn’t know.”

“Nothing else he’s done has amounted to much.”

He looked away. He was embarrassed, she thought. As if she was a pretty girl he wanted to get to know. She felt a strange sympathy for him for that.

“Are you done with me?” she said.

There were plenty of ordinary men to love. Ordinary monsters. Monster love. No different than extraordinary love. Her mind was wandering. Perhaps it had wandered away. She shifted in her seat. Her tailbone ached.

Fedir Andreivich sat outside the office of the deputy director. The appointment had been at the deputy director’s request, a note found on Fedir’s desk after returning from lunch. He’d have worn better clothes had he known. He scratched at an old stain on his trousers; a dried fleck of gravy or soup that had gone unnoticed until that moment. He had hoped for a promotion and a move into his organization. He no longer wanted to be an interrogator. The Deputy Director was said to be fair and even-tempered. Fedir would remember to cross his legs in such a way as to hide the spot. He crossed them then to see if this solution would work.

The door opened and Ilya Ivanovich appeared. Fedir stood. Ivanovich appeared surprised to see him.

“You’re not Yuri Mikhaylov?”

“I’m sorry,” said Fedir. “I thought you wanted to speak with me.”

“Don’t apologize.” Ivanovich barked with nearly the same harshness as his initial demand. “You didn’t misplace him. I thought he was leading the interrogation proceedings. Am I wrong?”

“Yes,” said Fedir. He was surprised with the directness of his own response. He softened his tone. “You are mistaken.”

Ivanovich seemed momentarily amused, and Fedir wondered if it was his boldness that had satisfied him. Ivanovich turned and gestured for Fedir to follow.

The inner office was the larger of the two rooms and dominated by an ornately carved desk. Two upholstered chairs were positioned in front of it. Ivanovich sat in one of these and motioned for Fedir to take the other. It seemed as though they were occupying a borrowed office, as if the meeting itself was surreptitious, and could end at any moment once the true occupant returned. Ivanovich leaned across the desk and opened a cigarette case. Again, it seemed an act of delinquency. He took one for himself and offered the box to Fedir. Fedir felt compelled to take one. After lighting them both, Ivanovich sat back and crossed one leg over the other.

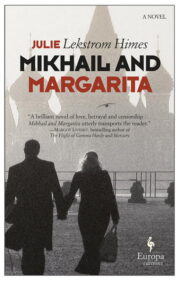

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.