They descended stairs then sloping passages. Walls were in places rough-hewn as though of a medieval dungeon. Her questions wrapped themselves in the pounding of her head and her growing nausea. Lights came and went overhead. She stumbled again and they hauled her upright. She wanted to tell them to take her back. She’d feel better tomorrow if they gave her more time. She’d speak nicely with the other women, share stories, express sympathy. She thought she had said that, but she heard her own voice, ragged and begging, utter different thoughts.

“Just tell me,” she said. Just say what was coming; tell her what she needed to fear.

They didn’t answer.

CHAPTER 23

Molière opened despite Margarita not being there to see it. This was the case with many things in those first weeks. Streetcars kept to their schedules. Newspapers continued to print. The world had changed—yet passersby appeared to give no notice to it. They bent their hats against the weather, they walked back and forth from work as before. The world had changed—yet it seemed to maintain some stubborn indifference to this, and if Bulgakov mistrusted it; if he resented it in fact, it was for this disregard.

The play’s reviews were generally positive. Stanislawski was pleased, and, perhaps more so, he was relieved. He arranged interviews for Bulgakov with major literary magazines and with Pravda. When Bulgakov missed his appointment for this, not once, but twice, Stanislawski first called, then came to his apartment to harangue him in person. This was important, the director told him. Actually, it was more than important—Bulgakov needed to earn the privilege of keeping Molière on the stage. He told him he would reschedule the interview once more—and that there would be others to follow. Now was the time to become a true literary figure. After everything he’d invested, that they both had invested. Bulgakov said he’d do better in order to get him to leave and Stanislawski slammed the door behind him.

Bulgakov cleaned up the mess from the night she was taken. He’d acquired a new kind of pragmatism with this. Rather than repair a tear, he turned the cushion over. Shattered picture glass was swept and prints were rehung on the wall without its protection. As if his anticipation of the agents’ return and further mischief was protection against it. Her blouses and skirts he hung in the wardrobe. Sweaters and slacks he returned to their drawers. Her boots near the door where they waited for her. Their belief in her release seemed alternately reassuring and absurdly naïve.

The novel itself remained on the table where they’d left it. One early morning when sleep gave no reprieve, he returned to his chair and laid his hand on the first page. It was as impenetrable as a grave. He put it back in the drawer of the wardrobe then lay down again. Still he sensed it as though that part of the room had settled under its weight.

He debated what to do about the curtains and one night he rehung them. They were rumpled from having sat in piles for too long. Most of the pins she’d used still lay on the sills; some had been scattered and, with the hanging of the final panel, he found himself on the floor, on his knees searching the seams between the floor’s planks for the last remaining ones. What looked like a pin was a grain in the wood, a stray thread, a strand of hair. He would go to pick it up and his fingers grasped air. The world had done this to him. Ilya had done it. Then one small part of his brain went past this to think absurdly, selfishly, childishly, perhaps she’d had some hand in it. How could he blame himself and go on? Did he know how hard it was to lay one’s hands on pins? He pressed his forehead against the wood. How could he have known?

Bulgakov posted letters to Stalin nearly every day. There was never any indication that they were read. He went to Lubyanka looking for Ilya but was turned away. He stood in long queues with the families of other prisoners. He thought they all looked the same—pale, shell-shocked. They spoke not at all to each other, as though this would acknowledge some terrible commonality. As though it would unduly test their faith that their particular case—their husband, their wife, their child—was different from the rest. They waited for the opportunity to plead with a guard whose lips were hidden behind a small metal slit in a wall. Ten-second conversations that were unvaried. The guard would review several lists for the given name. A rattle of paper might be heard but not always. Sometimes there was the odor of onions and animal fat.

Bulgakov wished he could talk to Nadya. He wondered how she had managed those weeks waiting for some bit of information, yet dreading it too. What would she have thought of this turn of events? Once again, her husband and his lover were aligned in ways that excluded her. Would she feel vindicated or would this be a different kind of loss? Or had all feelings been wrung dry?

“Margarita Nikoveyena Sergeyev.” The sound of it fled quickly and made for Bulgakov a renewed loneliness.

The voice paused. “I have no information available.”

How was that possible? “Every week I hear the same thing—do you know if she is even in there?” said Bulgakov.

There was another pause, and for a moment Bulgakov wondered whether if by deviating from the typical dialogue, he’d actually broken some internal mechanism. The voice returned.

“Is she out there with you?” it said.

“Of course not.”

“Then she is here.”

A woman behind him pressed against his coat. “You’ve had your turn,” she said. “Give it to another.” Bulgakov didn’t move.

“And if you were to have new information, what might that be?” said Bulgakov.

Another pause, then Bulgakov sensed a kind of sympathy to the words. “That she is no longer here, either.”

Bulgakov stood at the tram stop outside of Lubyanka, watching those who converged upon that spot waiting for their own particular route. He wasn’t certain whom he was looking for. There were office workers—men and women, older women, perhaps mothers in their own right, and younger, attractive ones. There were guards in uniform. Many read newspapers. Some smoked and kept watch down the avenue. Some stared into space. Several trams stopped and filled with passengers. Bulgakov continued to wait. The afternoon shadows began to lengthen. A women with a perambulator appeared. The baby was crying and the woman bobbed the handles, cooing into its cover, trying to soothe it. A youngish guard standing nearby glanced toward the child. Bulgakov could guess that from his angle he had some view of the carriage’s interior. Bulgakov surmised he was of lower rank given the few stripes across his sleeve. Perhaps the guard was only bored. Perhaps he was reminded of some younger brother or sister, some past time. He smiled slightly, and then, and Bulgakov’s heart rose with this, the guard’s expression shifted. There was a moment of understanding—the day was chilled, the wind stung, the afternoon had been long already and one could simply be hungry. Or bored and with only a child’s sensibility there would be no anticipation of what would certainly be relief once Mother could get it home. Yet unlike others nearby who either ignored or were irritated by the noise, unlike even the Mother who seemed to think jostling the buggy might provide some comfort, the guard seemed to understand the world of these things; he seemed to feel them all at once. It was there—one instant that said, Yes. I can imagine what you are feeling right now.

The tram arrived and the guard climbed in. Bulgakov followed.

His interview with Pravda, rescheduled now for the third time, was that evening. The tram was headed in a different direction.

CHAPTER 24

A clock hung on the wall inside her cell. For sixteen minutes each day, sunlight passed through a single, high window and painted a rhombus of light on the cement floor. For those sixteen minutes, she sat in the light, feeling the coolness seep through the fabric of her skirt. For those minutes the rest of the cell seemed darker.

Each day she followed the guards down two flights of stairs to a room that was painted white on the top and blue-grey on the bottom. Here her interrogators waited. There were three of them. She did not know their names. She called them Matthew, Mark and John. Matthew was handsome and in some ways her favorite. He wasn’t interested in learning of her anti-Bolshevik sentiments, if indeed she had any. He had imagination.

Their first session, he held her hand at the beginning as if they’d been formally introduced. He seemed to linger over it, admiring its structure, and for a moment she was self-conscious of his attention. He then let go.

“Take off your underwear,” he told her.

“What? No!”

There was an explosion of light, then pain. She fell to her hands and knees. No one in the room said anything or moved to help her. She touched the inside of her cheek with her tongue where it’d been torn by her own teeth. She got up, for a moment unsteady, then lifted her skirt, slid her underwear down to her ankles, and stepped out of them. She held them in her hands, her arms crossed over her torso. Tears came and rolled down her cheeks. Matthew nodded to one of the men behind her and her arms were lifted and extended over her head. Loops of rope were tied around her wrists and then to a hook that hung from the ceiling. The hook was raised until she was standing on her toes.

“Oh! Oh! Please! I can’t—please!” Her voice sounded muffled, her arms pressed against her ears. She wanted to cross her legs but couldn’t maintain her footing. Matthew didn’t respond. He walked around her slowly, slipping from her sight. She quieted, listening, breathing in short airy gasps. After a few moments he reappeared. He sat on a stool in front of her. He now carried a policeman’s baton. He stroked the hem of her skirt with it.

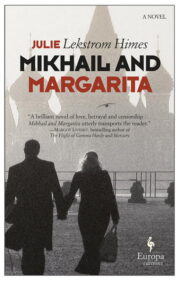

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.